CRU

April 7, 2025

CRU: 'Liberation Day' brings sweeping US tariffs

Written by Alex Tuckett & Henry Hao

Donald Trump has announced major increases in tariffs on almost all US trading partners, with the exception of Mexico and Canada. Taken together with the tariffs already announced since he took office, around $2 trillion (60%) of US imports are now facing significantly higher tariffs, at an average rate of around 20%.

These tariffs have the potential to push up inflation by 2 percentage points to 4 percentage points in the US and will depress already slowing consumer spending. For trading partners, the tariffs will reduce demand for exports and depress growth. Over the coming days, trade partners will almost certainly announce retaliation, which will hit US exports.

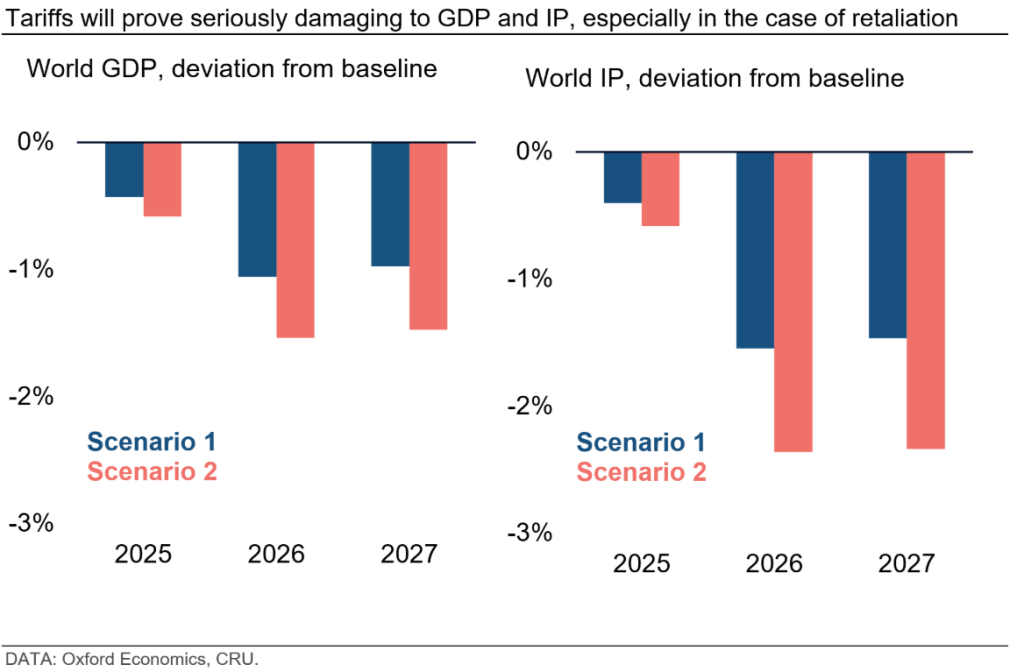

Overall, this means lower global GDP and industrial production, and therefore lower demand for commodities. Depending on the degree of retaliation, the Trump tariffs implemented since he took office are likely to reduce world GDP by between 1%–1.5%, and IP by 1.5%–2.4% by 2026. If the US counter-retaliates with even higher tariffs in a spiral of escalation, the economic costs could be even greater.

Reciprocal tariffs complicate the tariff picture and raise average costs substantially

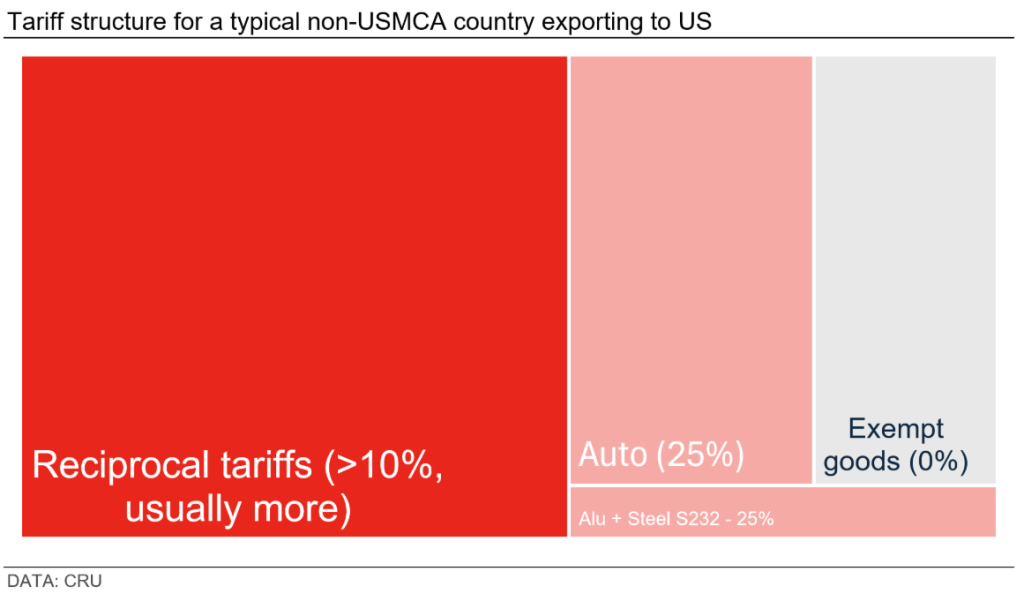

Taken together with other trade policies already introduced by the administration, this means most countries now face a range of tariffs on different sub-sets of their exports to the US:

Steel and aluminum continue to be charged a 25% tariff under Section 232. The new reciprocal tariffs will not be additional to this.

Autos (from April 3) and components (from May 3), including SUVs and light trucks, will also be subject to a 25% tariff. There is an exemption for USMCA-compliant exports. However, non-USMCA components in imports from Mexico and Canada will be subject to the 25% tariff.

Most other products will be subject to reciprocal tariffs at a minimum of 10%, but for most major trading partners this will be much higher.

A long list of products are exempt from reciprocal tariffs, including energy commodities, other raw materials such as most base metals, pharmaceuticals and semi-conductors.

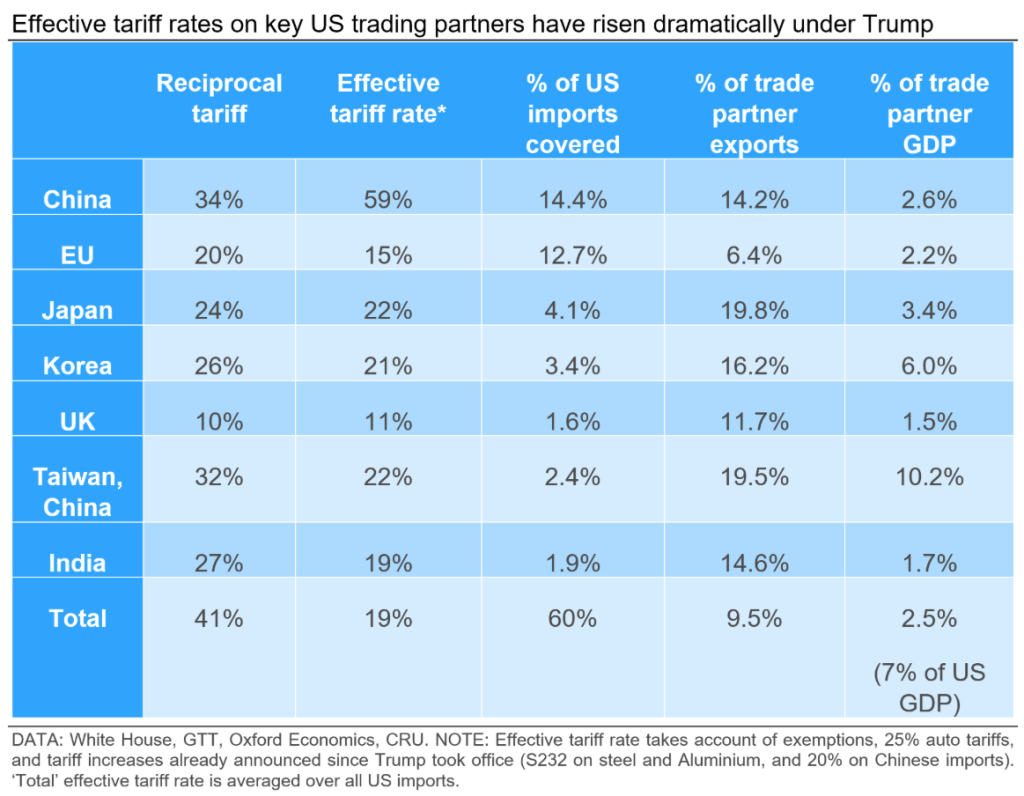

The combination of these tariffs – in particular the high reciprocal rates imposed on major trading partners such as China, the EU, Japan and Korea – will push effective tariff rates sharply higher, as shown in the table below.

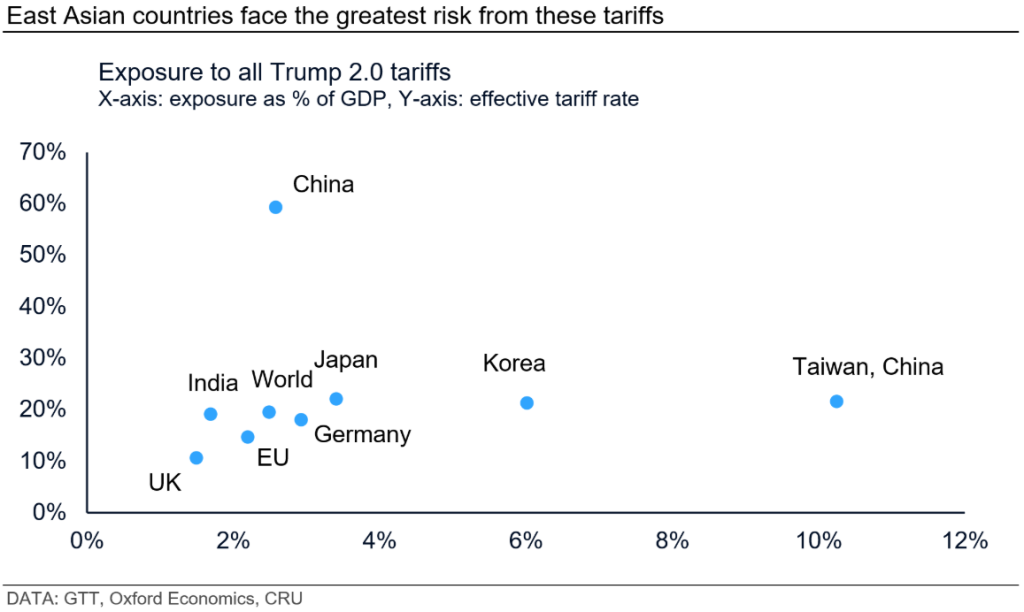

China is now facing exceptionally high rates of tariffs to export into the US. Japan, Korea and Taiwan, China are particularly exposed given the importance of exports to their economy. Although Europe faces lower exposure, relative to the size of its economy, this outcome is at the more severe end of the range of scenarios we outlined, and will be a serious headwind to the European industry.

Asian’s export powerhouses reeling from US tariff shock

The imposition of sweeping reciprocal tariffs by the US, particularly the escalated tariffs against China and other Asian exporters, threaten to fundamentally reshape global trade flows and commodity markets.

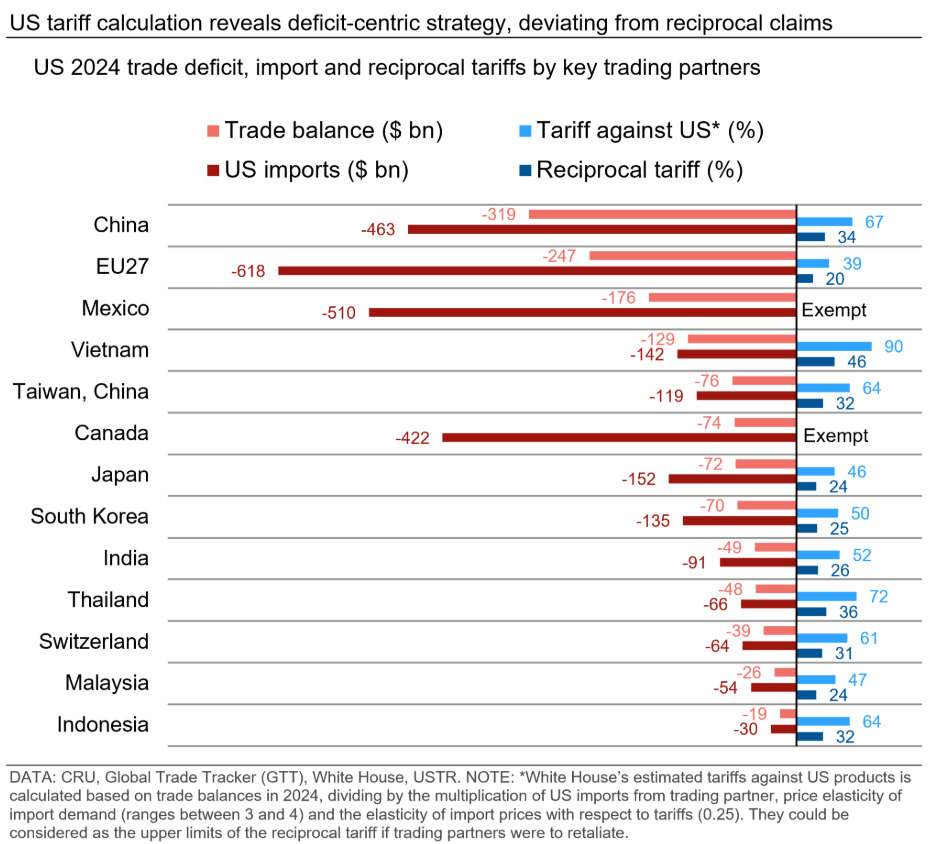

The USTR’s approach to calculating these tariffs (based on dividing a country’s trade surplus with the US by its total exports and halving this result) is significantly different from Trump’s original statements. This is because it focuses on reducing bilateral trade deficits rather than merely matching other countries’ tariff rates and trade barriers.

China now faces minimum tariff rates of 54%, and an average tariff rate of over 60%. It risks a substantial contraction in its trade with the US, potentially necessitating a dramatic restructuring of its export strategy and/or further stimulus measures to boost domestic demand. Similarly, other Asian economies like Japan, South Korea and Vietnam, despite their varying degrees of alliance with the US, are also confronted with substantial tariff burdens, forcing them to reassess their export strategies and supply chain configurations (see the chart below).

This widespread tariff imposition, exceeding prior expectations, is poised to trigger a cascade of trade diversion, forcing these countries to seek alternative markets and potentially leading to a fragmentation of global supply chains, thereby increasing economic uncertainty and volatility.

The US Treasury’s focus on “the dirty 15” markets, identified as primary contributors to the US trade deficit (see chart above), underscores a strategic shift toward a more comprehensive application of trade protectionism. This policy, targeting a broader spectrum of economies beyond the initial focus on China, Canada and Mexico, shows that no trade partner can remain unscathed.

Given the significant trade imbalances, East and Southeast Asian nations are particularly vulnerable, forcing them to diversify their export markets and reduce their reliance on the US. This could lead to the emergence of new trade alliances and regional economic blocs, potentially altering the dynamics of global commodity markets.

Moreover, the exemptions granted to certain commodities under existing S232 investigations – such as steel and aluminum, alongside the exclusion of Canada and Mexico – introduce further complexities, potentially creating arbitrage opportunities and distorting market signals. Faced with a blanket 10% tariff, businesses may opt to relocate trans-shipment operations from Vietnam and Thailand to lower-tariff regions like Panama and Brazil, seeking to minimize costs rather than returning manufacturing to the US.

The Trump administration’s rationale, focusing on rectifying trade imbalances and revitalizing domestic manufacturing, carries significant economic risks. The potential for retaliatory measures from affected nations, as evidenced by China’s pledge to respond, could escalate into a full-blown trade war, destabilizing global markets and hindering economic growth.

The auto sector is particularly exposed

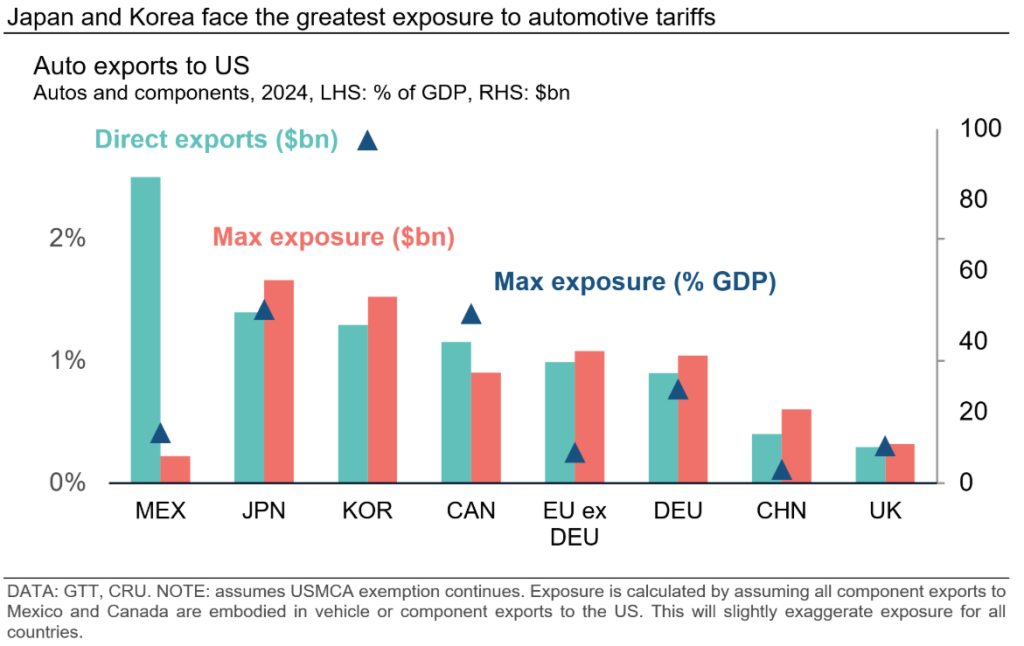

A 25% tariff on automotives and auto components was announced by Trump on March 26, and was confirmed on April 2. Crucially, these tariffs have an exemption for USMCA-compliant vehicles and parts.

However, automotives and components from Mexico and Canada will still be liable to a tariff on any embodied non-USMCA components. For example, Toyotas assembled in Mexico with Japanese engines, or VWs with German transmissions, would pay a partial tariff if exported to the US.

If this USMCA exemption holds, this will be a vital reprieve for Mexico. Based on direct trade, it is by far the largest single exporter of both autos and components to the US. However, with the exemption in place, Japan will be most exposed in absolute terms, and Korea as a share of total exports and GDP. Germany will be, by far, the most exposed country in Europe, but will have less concentration in the US market than Japan or Korea. China will be little affected, as high tariffs have already kept out most exports to the US with the exception of some component trade.

The auto tariffs will result in some switching of production to existing US sites, where OEMs and component suppliers have the means to do this. However, it will also push up auto prices for consumers, destroying demand.

The tariffs will be bad for growth in the US and its trading partners, especially if there is a spiral of retaliation

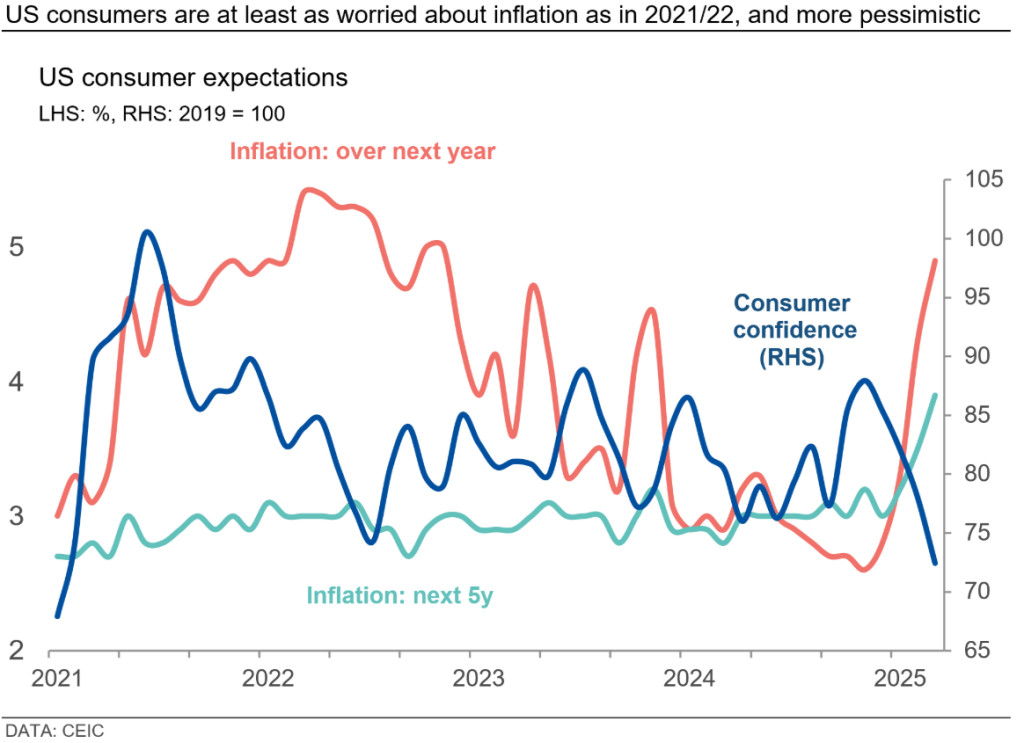

These tariffs come at a bad time for US consumers and the economy more generally. Confidence has already been falling, partly because of the degree of policy uncertainty (not least about tariffs, but also immigration policy and government spending cuts), and also due to US consumers spending heavily for several years and showing signs of being overstretched. Consumer inflation expectations have risen, consumer confidence has fallen, and retail sales and PMIs have all decelerated since Trump took office (see charts below).

Without any behavioural response – trade divergence, switching of spending to domestic alternatives or other goods – these tariffs would raise around $650 billion of revenue. This is effectively a fiscal tightening of around 2.2% of GDP.

Although some of the costs will be absorbed by exporters given the breadth of these tariffs, much of the cost will be passed on to US consumers. Full pass through of the tariffs would imply consumer prices rising by between 2% and 4%. This would push US CPI inflation (which was 2.8% year over year in February) to between 5% and 7%, depending on how quickly costs are passed down supply chains.

Based on simulations using the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model, these tariffs will reduce US GDP by 0.5% in 2025 and 1.5% by 2026, even when assuming no retaliation by trading partners beyond what has been announced already (for example by China). Depending on how the impacts unfold quarter by quarter, there could be a mild recession. If trading partners fully retaliate one-for-one, it’s very likely to push the US into recession.

Full like-for-like retaliation is unlikely. The EU has limited trade options – tariffs on energy would be self-defeating, and product standards already substantially restrict agricultural imports from the US. Smaller trading partners may try and bargain rather than retaliate.

However, there will be retaliation in some form. For example, if the EU were to use regulatory powers to squeeze the profits of US tech firms, this could have serious repercussions for profits and stock market valuations. Furthermore, a consumer backlash against US products is already costing US firms market share in Canada – and impacting Tesla sales worldwide. This could spread, damaging US exports.

The tariffs will be damaging for trade partners and global growth too (see charts below). In a scenario without any retaliation beyond what has already been announced – which is highly unlikely – global GDP will be around 1% lower. In the event of full retaliation, the impact increases to 1.5%. Impacts for IP are larger, at 1.5% and 2.4% in 2025, and are more persistent.

Although trade wars may increase the prices of some commodities in particular places (e.g. steel and aluminum within the US), they ultimately raise costs, squeeze consumer incomes, curtail investment and destroy demand in end-use sectors, which is deflationary for commodities.

Possible outcomes: De-escalation or full-scale trade war

It remains highly uncertain where trade policy will go from here. Some countries may succeed in securing concessions from the US by reducing their own tariffs or other barriers, or making commitments to buy more US exports or invest in the US. However, others may retaliate, leading to escalating tariffs. Although the current situation stops short of the worst case multi-lateral trade war outlined in our scenario analysis last year, this is clearly a very serious moment for the global economy.

We will be monitoring developments closely and will adjust our forecasts for growth in our Global Economic Outlook published at the end of April. You can continue to keep up to date with developments in global trade and what it means for commodity markets through CRU’s Economics research.

This article was first published by CRU. To learn about CRU’s global commodities research and analysis services, visit www.crugroup.com.