CRU

March 7, 2025

CRU: Will US tariff policy be transactional or transformational?

Written by Alex Tuckett

Markets are struggling to guess the direction of US tariff policy amid repeated U-turns. This week the US imposed steep tariffs on its three largest trading partners after previously delaying them. However, concessions have already been made, with a further one-month delay on having to pay tariffs on most trade with Mexico and Canada.

If they are maintained, the global economic cost of these tariffs – and potential future ones against the EU and other trading partners – will be considerable, especially for the manufacturing sector. However, there still remains great uncertainty about the path of tariff policy from here.

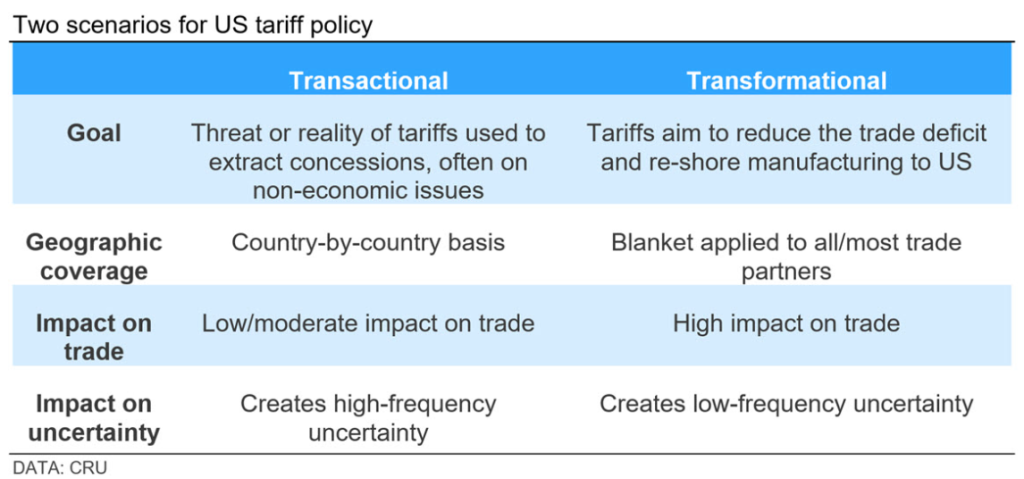

The path of tariffs will depend in great part on what the underlying aims of the Trump administration are – whether tariffs are being used as a “transactional” tool or a “transformational” one. More prosaically, policy will depend on the reality of economic effects, their public perception as costs begin to bite and the domestic political reaction.

Tariffs raised on major trading partners – and delayed again

The 25% tariffs on all goods from Mexico and Canada – with a lower rate of 10% on Canadian energy products – came into effect on March 4 and were subsequently put on hold for another 30 days. These tariffs had been delayed after their initial announcement in early February, subject to discussions on border security.

It appears these tariffs will be stacked on top of the 25% Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum. This means that steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico will be subject to tariffs of 50%.

However, following the announcement, a one-month delay on tariffs on US automotive OEMs was introduced. Now, the delay will be extended to all trade covered under the USMCA agreement – which is most trade between the countries.

Canada immediately announced retaliatory tariffs, which will eventually cover around $107 billion of US exports – almost 30% of US exports to Canada. Mexico was due to announce retaliatory measures on Sunday, March 9, however, this may now be delayed given the pause to the US tariffs.

The US also introduced an additional 10% tariff on imports from China. This comes on top of the 10% tariff introduced in early February, and brings the average levy on Chinese imports to almost 40%.

US tariff policy could be transactional or transformational

Many commentators have so far assumed that tariffs will be used in a “transactional” way to extract concessions from trade partners, potentially on issue unrelated to trade or economics (e.g. border security).

Increasingly, it is looking as though the imposition of tariffs has “transformative” aims instead – reducing the US trade deficit and re-shoring manufacturing.

The table below summarizes the key differences we can expect. In short, transformational tariffs are like to be broader, deeper, longer-lasting and more damaging to the global economy.

‘Transformational’ objectives will not be easily achieved

The goals of reducing the US trade deficit or re-shoring manufacturing will not be easy to achieve with tariffs alone.

During Trump’s first term, when a series of tariff increases on Chinese imports was put in place, the trade deficit with China did fall. However, the aggregate US trade deficit did not. This was partly due to trade diversion, especially through Southeast Asia and Mexico. Broader tariffs could be used to try and tackle that.

However, it also reflects the underlying truth that a trade deficit reflects an excess of domestic spending over income. If tariffs are actually used to reduce the fiscal deficit (instead of being recycled into cuts in other taxes), or reduce consumer spending, then the trade deficit will fall. But this will be painful for US (and global) growth.

Similarly, the Trump 1.0 tariffs appeared to have little positive effect on the US manufacturing, partly because they hurt export competitiveness. Tariffs push up import costs for domestic manufacturers, making goods more expensive and squeezing real consumer demand. They also reduce competitiveness for exporters – particularly as tariffs tend to lead to a stronger dollar, and trade partners retaliate with their own tariffs against US goods.

The administration is unlikely to achieve a quick win in its trade objectives. This suggests that, if the ultimate goals are ‘transformational’, we will see a continued ratcheting up and/or broadening of tariffs throughout Trump’s presidency.

Tariff aspirations will meet economic and political reality

If the current set of tariffs (including the steel and aluminum tariffs) are maintained, they will have a highly damaging effect on the economies of Canada and Mexico.

Based on simulations using the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model, Canadian GDP will be 1.4% lower in 2025 and 2.4% lower in 2026, pushing the country close to a recession. Mexican GDP is 0.9% lower in 2025 and 1.8% lower in 2026. The impact on China is more modest (0.3% and 0.7%), as China is a much larger economy with less dependence on exports to the US.

Although the damage to the US economy is less severe than for Canada and Mexico, the tariffs still reduce US GDP by around 1%. Given the increasing number of signs in the data that the US economy is slowing, this will be a highly unwelcome headwind.

It will be particularly severe for the automotive and construction sectors. Highly visible increases in consumer prices – for instance for certain food items, autos and electronics – will be politically very painful for the Republicans, especially given they campaigned on a platform of reducing prices after the high inflation of the Biden administration. Higher inflation, even if temporary, will also complicate the response of the Fed to a slowing economy. Politically sensitive export sectors such as agriculture will be hit with retaliation.

Although other countries face much lower average tariff increases (only facing the additional steel and aluminum tariffs), there is still some spillover impact as lower trade volumes spread through supply chains and from weaker spending in the protagonists of the trade war. World GDP is 0.4% lower in 2025 and 0.6% lower in 2026. Industrial production is 0.5% and 0.9% lower respectively.

In a wider trade war scenario where the US proceeds to impose 10% tariffs on all other trading partners, followed by retaliatory tariffs of 5%, the impact on the world economy will be greater: GDP will be 0.6% lower in 2025 and 0.9% in 2026, with IP 0.6% and 1.2% lower. The impact on US GDP grows to -1.4% in 2025.

The tariff increases of Trump’s first term were enacted against the background of a strongly-growing economy, and followed the domestic tax cuts introduced in the first half of his term. These tariffs will be broader, deeper and more painful than under Trump 1.0, and they come against the background of an economy that may well be slowing. How they are perceived domestically will be the key variable that determines they remain, grow or are rolled back.

This analysis was first published by CRU. To learn about CRU’s global commodities research and analysis services, visit www.crugroup.com.