Market Data

September 14, 2024

Price on trade: Evaluating potential approaches to emissions policy and border measures

Written by Alan Price & Ted Brackemyre

The only way to achieve net zero goals worldwide is to significantly reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of the global steel industry. And emissions standards can play a key role in encouraging (or discouraging) steel decarbonization. In that spirit, earlier this year, the Biden administration established a climate and trade task force, aimed at a promoting “a global trading system that slashes pollution, creates a fair and level playing field, protects against carbon dumping, {and} supports good manufacturing jobs and economic opportunity.”

These are ambitious and laudable goals. Across sectors, the United States has a significant carbon advantage over many of its economic competitors. This is certainly true in the steel industry, where American manufacturers are among the lowest emitting in the world. In other words, when it comes to steel, climate-focused trade policy can go hand-in-hand with US competitiveness.

However, as the Biden administration’s new task force evaluates potential carbon border measures, it remains an open question as to whether or not they will adopt a differentiated emissions standard that would actually encourage higher emissions and give up the US carbon advantage.

As Dr. Ali Hasanbeigi, the CEO of Global Efficiency Intelligence LLC, has shown in one recent analysis, there are not significant differences in emissions between many electric furnace producers (or between many blast furnace producers) worldwide. Rather, the principal reason behind the US carbon advantage is that a substantial majority of the steel made in the United States is produced in electric furnaces.

As we noted in a prior article in SMU, the emissions intensity of an electric furnace is roughly 70% lower than that of a blast furnace. And one recent study finds that, in the United States, the Scope 1-3 emissions intensity of hot-rolled products made in a blast furnace (2.40 MT CO2e) is more than double that of hot-rolled products made in an electric furnace (0.97 MT CO2e).

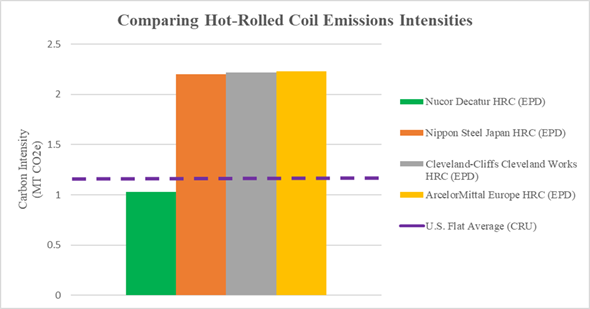

The environmental product declarations (EPDs) issued by some of the largest steel producers in the world highlight the faulty logic of differentiated emissions standards. Based on publicly issued EPDs, the emissions intensities for hot-rolled steel coil production are approximately twice as high for blast furnace facilities as for electric furnaces. For example, in the United States, Nucor’s mill in Decatur, Ala., (an electric furnace) produces hot-rolled coil at an intensity of 1.03 MT CO2e per ton of steel, whereas Cleveland-Cliffs’ Cleveland Works (a blast furnace) produces the same product at 2.22 MT CO2e. Similarly, Nippon Steel’s Japanese and ArcelorMittal’s European blast furnaces report hot-rolled coil emissions intensities of 2.20 MT CO2e and 2.23 MT CO2e, respectively, in their EPDs.

These data show that what drives emissions in the steel industry is the gap between scrap-based electric furnaces and ore-based blast furnaces. And differences among blast furnace producers worldwide are largely caused by their relative scrap use, not the carbon efficiency of their furnaces, according to CRU. It is also important to remember that very little flat production outside the United States is via scrap-based electric furnaces. Indeed, because US flat production is electric furnace focused, CRU has calculated an industry-wide emissions intensity of 1.2 MT CO2e for flat products in the United States, which is among the lowest in the world.

Further, many of the newest and most efficient blast furnaces in the world are in China, and they are highly competitive on emissions compared to US blast furnaces. Yet, the Chinese industry as a whole is much dirtier due to the widespread American adoption of low emissions technologies, like electric furnaces, and the predominant use of scrap.

Why do these data matter? Consider a border measure that uses a dual standard. Imported steel made in electric furnaces would have to meet the US electric furnace average. And imported blast furnace products would have to meet the US blast furnace average.

This means that instead of being compared against the overall US hot-rolled coil average, imports from Nippon Steel and ArcelorMittal (two of the world’s largest and highest emitting flat-rolled producers) would be judged against the US blast furnace average. And hot-rolled coil imports from Nippon Steel (2.20 MT CO2e) and ArcelorMittal (2.23 MT CO2e) would both fall below the US blast furnace average (2.40 MT CO2e).

That hardly provides a bulwark against dirty imports. Electric furnaces and blast furnaces make the same steel products, meaning that these high emissions imports would effectively skirt the border measure and compete head-to-head in the market with low emissions US products.

In contrast, as shown below, if the domestic average for total US flat production (1.2 MT CO2e) is used as the standard, these higher emission steels from ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel would be required to pay substantial border fees.

The consequences are just as perverse when a dual standard is applied to long products. The Scope 1-3 emissions intensity for US long products made in electric furnaces (0.61 MT CO2e) is typically at least three times lower than the emissions intensity of imported long products made in blast furnaces. One leading integrated rebar producer reported a long products carbon intensity of 2.3 MT CO2e in 2023, which is consistent with other blast furnace producers and shows the equally large divide between clean and dirty long production.

Yet, since there are no long producers using blast furnaces in the United States, but roughly 50% of global long products are made in blast furnaces, the emissions intensity of blast furnace imports would be compared against a made-up emissions threshold that does not represent the actual experience of the US industry, which is far cleaner. This would result in greater volumes of high emissions imports entering the United States than under a single standard. The biggest loser in this scenario would be the union and non-union mills making long products in the United States.

Consequently, it is not clear to us how differentiated emission standards as part of a carbon border measure promote decarbonization or American competitiveness. Any carbon policy that distinguishes between production processes in establishing emissions standards does so at the direct expense of the low-emissions producers whose advantage is greatest when the same standard is applied to all companies. And when applied at the border, even the highest-emitting American producers are disadvantaged by a dual standard. Put simply, a dual standard effectively encourages imports with higher emissions than the majority of steel production in the United States.

Especially as the European Union’s (EU) Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) continues to enter into force, this will have a significant impact on the American steel market. The EU CBAM uses a single emissions standard, applying the same emissions costs to all products regardless of their production process.

This means that high emissions steel will be effectively barred from the European market. As the CEO of a leading non-EU, integrated steelmaker said in a recent interview, they “may become uncompetitive in the EU market” because of the CBAM. This will have massive trade diversion effects. And if the United States opts for a differentiated approach (or no border measure at all), we will be barraged with blast furnace imports that can only meet the blast furnace standard, that are from producers who are much higher polluting than the US industry, and that have been priced out of the EU market.

Given the desire for climate action, and the urgent need to secure American competitiveness vis-à-vis higher emitting foreign producers, it appears obvious to us that a single standard should be the only approach under consideration for any carbon border policy.

Editor’s note

This is an opinion column. The views in this article are those of an experienced trade attorney on issues of relevance to the current steel market. They do not necessarily reflect those of SMU. We welcome you to share your thoughts as well at info@steelmarketupdate.com.

Alan Price

Read more from Alan Price