Overseas

February 28, 2022

CRU: Russian Disruption Means Big Global Supply Gaps

Written by Matthew Watkins

By CRU Principal Analyst Matthew Watkins and Research Analyst Christopher Dix, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service, Feb. 28. Contributors Erik Hedborg, Dmitry Popov, Ryan McKinley and Clare Hanna.

Following the escalation of the situation in Ukraine, we set out what positions Russia has currently in the export market through the steel value chain. In the short term it is likely that the market will see disruption in any or all of these areas. In turn that disruption could stem from multiple sources such as compliance with international sanctions, risk minimization around possible future sanctions compliance, interruptions to logistics chains, or insurance and financing risk. However the disruption arises, at this stage we can say that it is both likely and given the scale of Russia’s involvement in the global industry, likely to be material to the market.

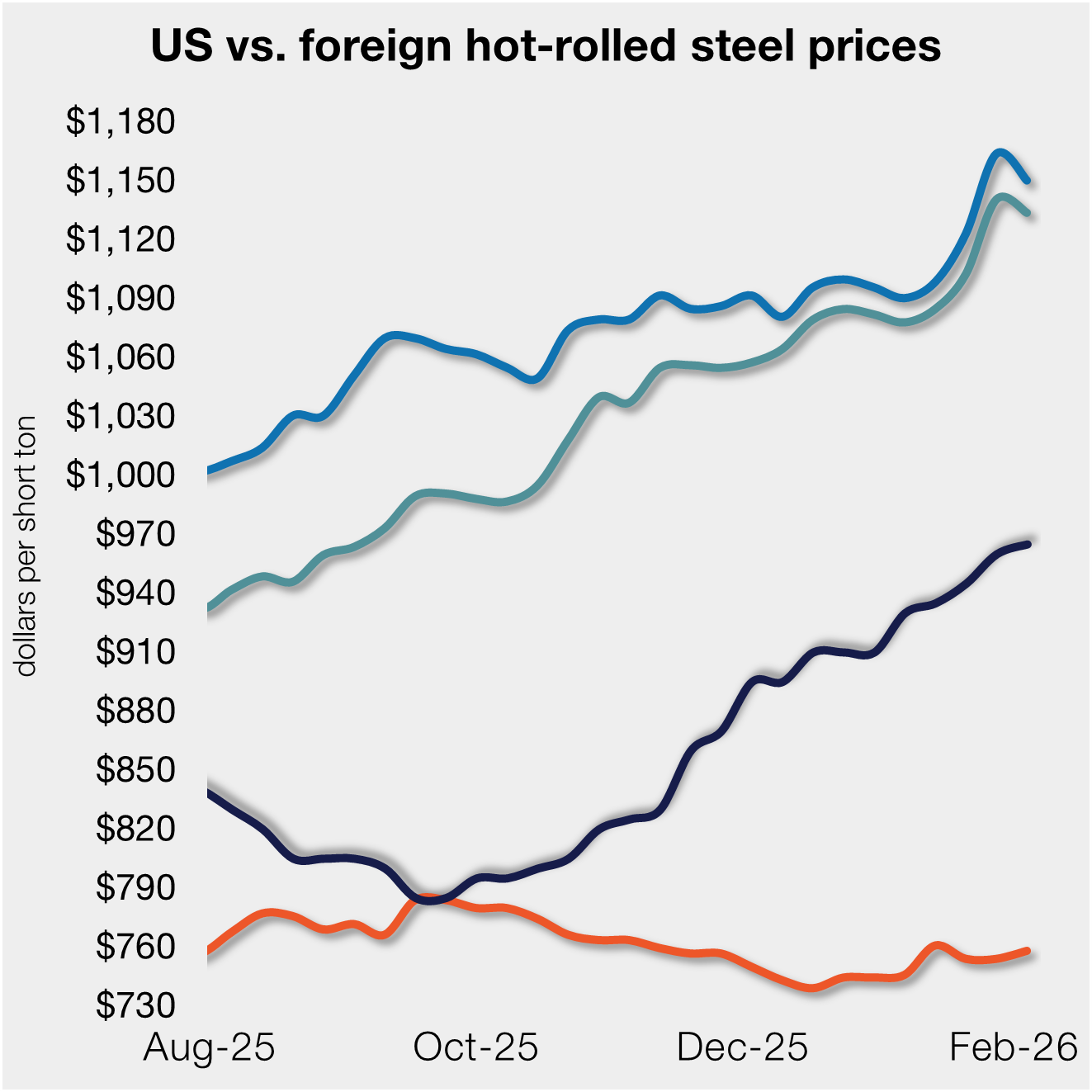

Over recent months as geopolitical tensions increased, many buyers of Russian and Ukrainian products sought to proactively and protectively re-source as well as build additional buffer stock. These efforts have proved to be well-founded and will now probably enter a new, more urgent, phase. For some products within the steel value chain there are potential alternate sources available; something that is not necessarily true of all the commodities that Russia produces. But, where available, these other sources are likely to come at an increased cost and it seems likely that in terms of steel prices the short-term implication is sharply higher.

Raw Materials: Significant Pain Points in Pellet, Coal, Pig Iron and HBI

Iron ore: An important source of pellet, but otherwise a minor seaborne supplier

Russia is the fifth largest iron ore producer in the world with 107 Mt of production in 2021, but the vast majority of the volumes stay on the domestic market. This makes Russia a relatively small supplier to the seaborne market. However, the country is an important supplier for one specific segment within the iron ore market – pellets.

As with all countries in CIS, most of the ore in Russia is magnetite and is sold either as a high-grade concentrate or as pellets. Total exports amounted to just over 20 Mt in 2021, with only half of the volume being transported by sea. The country’s largest iron ore producer is Metalloinvest, with mines and pellet plants located just north of the border with Ukraine. The company is the world’s second largest pellet supplier behind Vale with 24 Mt of pellets produced in 2021, of which ~6 Mt was exported to the seaborne market. Another important iron ore producer with a high proportion of pellet is Severstal, located in Murmansk in the northwestern parts of the country. Severstal produces ~12 Mt of pellet each year, with exports generally ranging between 3-5 Mt/y. Finland and Germany are the two most important markets for these products, each taking ~1 Mt/y.

Most of Russia’s iron ore and steel exports are shipped from the port of Novorossiysk, just to the east of Crimea.

Coal: Russia is a major supplier, especially to markets in Asia

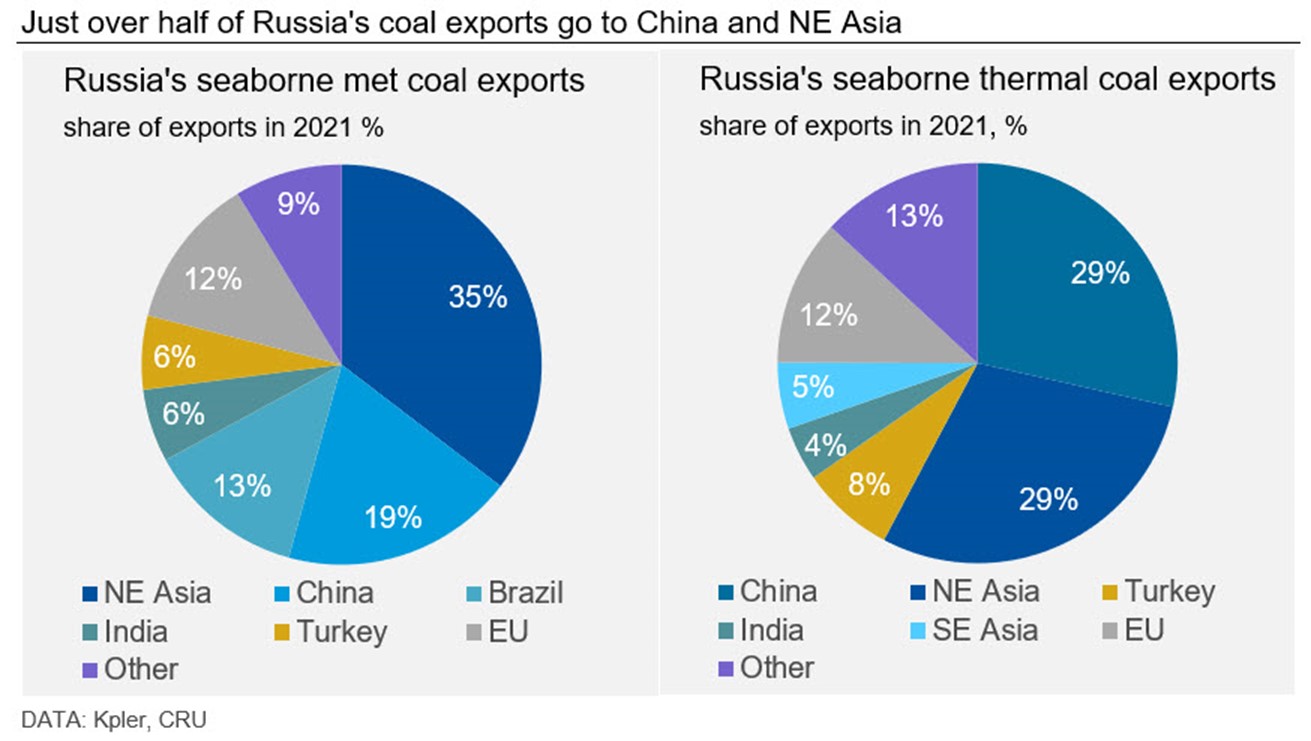

Russia is the world’s second largest exporter of metallurgical coal and third largest exporter of thermal coal. In 2021, its share in global exports was 16% for metallurgical coal and 17% for thermal.

Around 54% of Russia’s seaborne metallurgical coal exports and 58% of seaborne thermal coal exports went to China and Northeast Asia last year. EU countries accounted for around 12% of Russia’s seaborne exports for both metallurgical and thermal coal.

However, a substantial amount of Russia’s coal exports goes to the EU countries by rail. In 2021, 70% of EU’s total thermal coal imports came from Russia.

Any sanctions that prevent exports of coal from Russia are likely to have substantial impacts on already very tight global coal markets, leading to rising prices. For the EU, specifically for thermal coal, it would be almost impossible to find alternatives as supply from other countries has already been running around full capacities.

Scrap: No longer a big deal

Russia’s importance to the global scrap market has dwindled over the years. Prior to the GFC the country was the world’s largest net scrap exporter but this position has reduced substantially. As the Soviet-era fund has diminished, export duties have been imposed with the goal of retaining more for domestic use. The export duty on scrap has been in place for a long time, but it has been substantially increasing over the past year and it is no longer profitable to export scrap out of Russia.

In 2021, the top three destinations for Russian scrap were Turkey, Belarus and South Korea. Due to export duty implementation, Russian share of Turkish scrap imports decreased from 12% in 2018 to around 8% in 2021. Meanwhile, the share of Russian in EU scrap imports decreased from 18% to 6% over the same period. So far in 2022, the Russian export scrap market has been in a lull.

Pig iron: One of only a handful of big suppliers

Russia is the largest pig iron exporter to the global market. Last year around 35% of U.S. and 28% of European pig iron imports came from Russia. Any disruptions to shipments of pig iron will lead to a substantially tighter market. While Brazilian producers may help alleviate some of this shortage, the country cannot produce enough to meet global demand, and consumers will have to rely more heavily on prime grade and other ore-based metallics. Another alternative supplier would be Ukraine, which is also a major pig iron exporter, but given the current uncertainty there, any disruption stemming from the conflict will probably cause global pig iron prices to spike, especially in the near term.

HBI: Russian exports are more than half the global total, but lots goes to China

Russian DRI/HBI exports account for almost 60% of the total global volume traded. Last year Russia supplied around 4Mt of DRI/HBI to the global market and 34% of this was directed to China, which may remain an open trade route. A further 23% went to Italy and Spain jointly. Volumes going to such destinations as Turkey, the USA, other European countries are much smaller and amounted to 1-4% of the 2021 total.

Ferroalloys: Impact depends on the product

Russia is the second largest exporter of ferrosilicon after China, with a share of ~15% of trade and significant exports to Europe, Japan, South Korea and Turkey. Russia accounted for almost 50% of U.S. FeSi imports last year. While there are Russian producers of manganese alloys, these are smaller, and the destinations sufficiently diverse to mean the impact would be limited. Some European ferroalloy producers use Russian coke, electrodes and carbon products in their production processes. While there are alternatives to these, there may be a cost penalty and/or a short-term disruption risk.

Steel: Major Risks to Global Semis Trade and to Europe

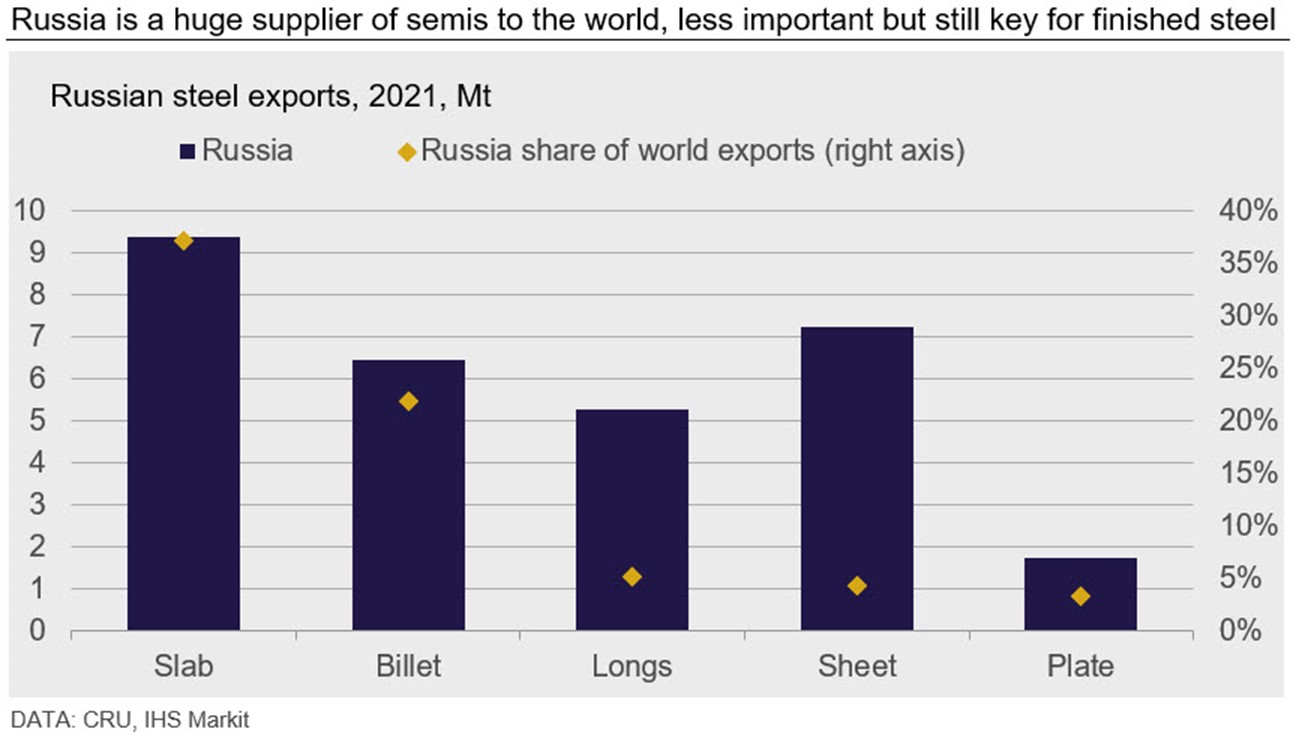

Russia is the largest exporter of both slab and billet to the world, based on 2021 export volumes. In finished steel it is less systemically important but still among the world’s key suppliers, ranking as the 6th largest longs exporter and 8th largest flats exporter globally.

A further point to note is that Russia is one of the lowest-cost suppliers in the world across multiple steel products. This will play into the likelihood that any alternate sourcing options may be more expensive.

In 2021 Russia exported 30 Mt of semifinished and finished steel products, which is slightly more than 8% of the total steel trade. Most of the Russian exports were directed to Europe, Turkey, Mexico and the CIS region. Turkey is a major consumer of Russian steel with 13% of total export volumes in 2021. Mexico and Taiwan, China, have also been major destinations as well, with 12% and 9%, respectively.

Russia’s key export market is Europe. Around 8.8 Mt of all semifinished and finished steel was shipped to the EU last year, which is roughly 30% of the total export flow. At the same time, in 2021 Russian steel represented around 22% of all EU imports; hence the dependency is mutual. Sanctions which may potentially result in the disruption of supply from Russia will create a tighter market where substitute products may cost more compared to low-cost Russian steel.

Based on 2021 data billet exports are predominantly directed to Turkey (20%), Taiwan, China (19%), the EU (15%), the Philippines (9%) and Kazakhstan (9%).

Slab exports are heavily weighted to EU destinations, with around 40% of the total shipped there. Europe has a significant re-roller sector, especially in plate, which is largely based on Russian and Ukrainian slab. Mexico and Taiwan, China, are the two other major destinations, with Mexican shipments significantly higher than historically normal in 2021, though consistently a major trade partner. Turkey is also an important customer with about 5% of total slab shipments. Turkish mills typically dynamically switch between making and buying semis depending on how the relative margins shift for each option. Lack of slab may therefore mean increased buying interest from Turkey for scrap.

Russian longs exports may be relatively insulated from geopolitical disruption. In 2021, almost 50% of longs exports were within the CIS region. Again, the EU is a key destination with 16% of exports; otherwise, Israel and Turkey are the other major longs markets for Russia.

Flats exports do also have a significant CIS component but at around 20% of total the export portfolio is more internationally oriented than longs. About one-third goes to the EU and slightly more than 20% to Turkey.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com