Prices

September 10, 2019

CRU: U.S. Iron Ore Supply Responding to Market Swings

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Senior Analyst Erik Hedborg

Part two of our three-part series: What’s next for U.S. iron ore production?

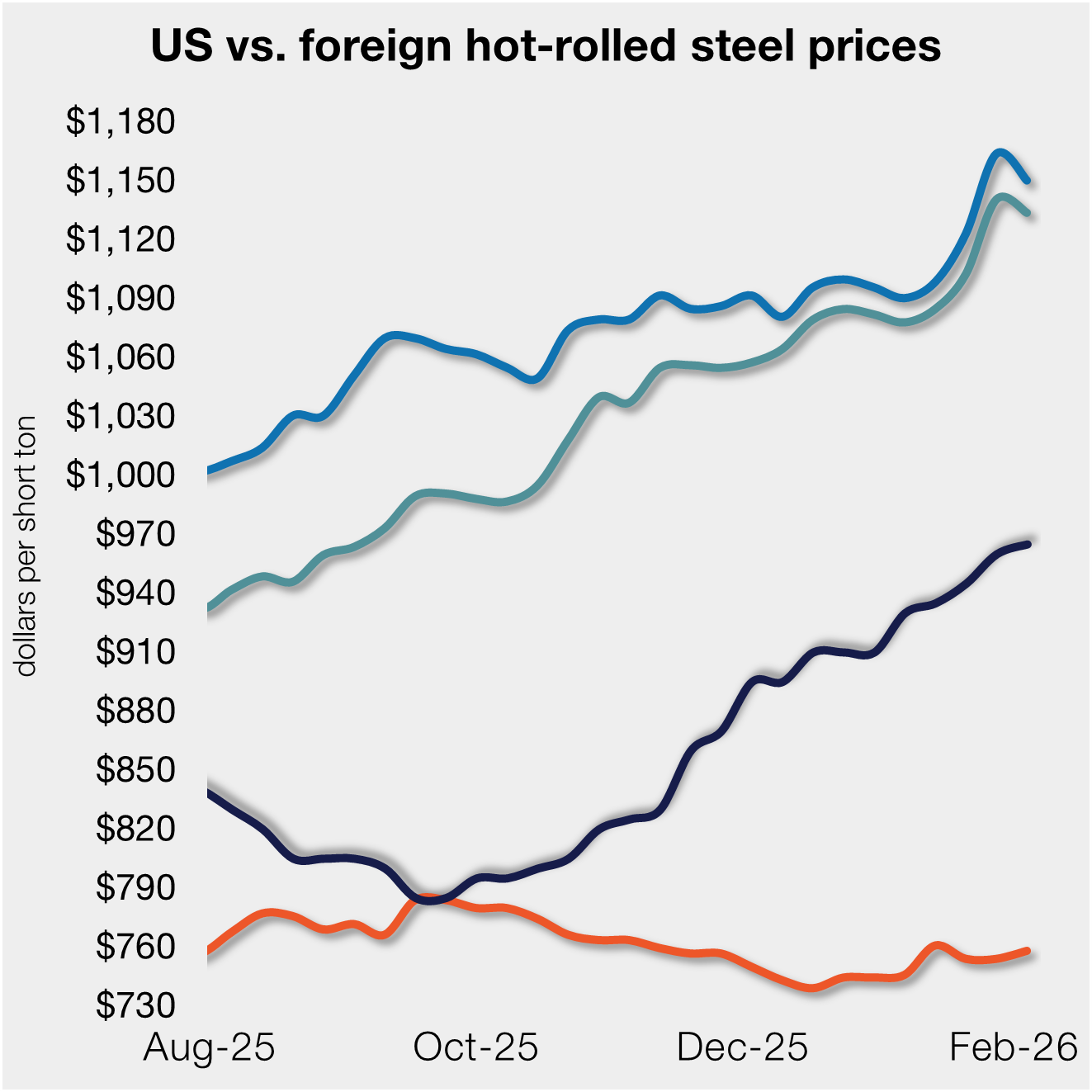

After a remarkably profitable 2018, the U.S. steel industry has suffered a setback in 2019 as steel prices have dropped sharply on weaker than expected demand. Steel margins have turned negative and production cuts have been announced by U.S. Steel. However, the good years did result in capacity investments and renewed interest in iron ore assets in the Mesabi Range. In part two of this series, we outline how the recent industry changes are altering the landscape for U.S. iron ore production.

Idle Blast Furnaces to Reduce Domestic Iron Ore Demand

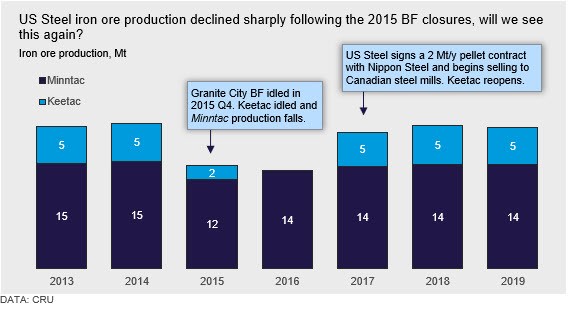

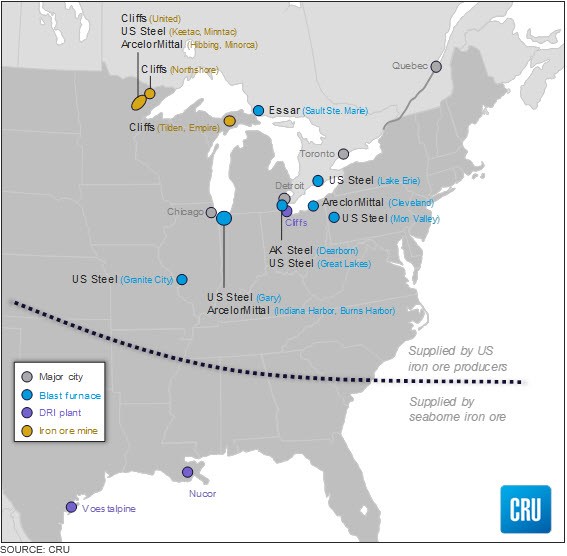

In 2019 Q2, U.S. Steel announced plans to idle three BFs located in Slovakia, Gary (Ind.) and Great Lakes (Mich.). The two U.S. BFs previously consumed 2.7-3.0 Mt/y of pellets from U.S. Steel’s own Keetac and Minntac sites. This situation is similar to that in 2015 when the company decided to shut two BFs at Granite City, a complex that consumed close to 3 Mt/y of pellets.

In 2015, steel and iron ore prices reached a bottom and U.S. Steel took the decision to idle the Granite City works in Q4 that year. As a result, the company’s own pellet consumption fell by nearly 3 Mt/y. After the closures, U.S. Steel’s remaining pellet needs were supplied entirely from Minntac. However, weak demand for pellets around the Great Lakes and on the seaborne market resulted in U.S. Steel shutting the Keetac mine and the company stopped selling pellets to third parties within the country. As a result, 1-2Mt of 3rd party pellet sales were removed from the merchant Great Lakes market. In addition to pellets, U.S. Steel imports ~1 Mt of fines and concentrate from Canada and Brazil for the company’s only operating sinter plant at its Gary works.

The situation changed quickly in the following years as the Samarco Fundão tailings dam accident caused a pellet shortage on the seaborne market and pellet premia began climbing. With such high pellet prices, U.S. Steel found it economical to export pellet, and a 2 Mt/y pellet contract with a Japanese steelmaker was signed. More recently, Granite City reopened, partly as a result of Section 232 import protections, and Keetac once again operated at full capacity, serving both U.S. Steel’s own BFs and the export market.

Now, the latest spate of BF idlings come at a difficult time in the seaborne pellet market. Pellet supply is strengthening, while demand in Europe, MENA, JKT and the U.S. weakens. With premium quality lump now being shipped from Baffinland and the return of Vale’s Brucutu mine, which is one of Vale’s key sources of pellet feed, it will be difficult for U.S. Steel to find buyers for its excess pellet production. Although the company was able to export at the high pellet premia during the period 2017-2018, we do not think that this arrangement is sustainable in the long term, especially as CRU expects further recovery of pellet shipments from Brazil in the coming years. Hence, the drop in U.S. pellet consumption is likely to force a reduction in iron ore production for U.S. Steel.

The decline in iron ore production will likely come from Minntac. The loss of iron ore consumption from the most recent round of BF idlings is ~1.2 Mt/y lower than the 2015 idling. By reducing production at Minntac, they would be able to keep the Keetac mine open. According to CRU’s Iron Ore Cost Model, Keetac is a more profitable mine than Minntac, sitting lower in the cost curve by ~$8 /t.

DRI–Will It Save U.S. Iron Ore Production?

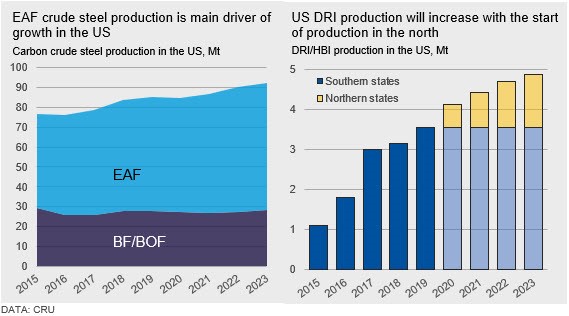

Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) are playing a more significant role in U.S. steel production. They currently account for ~68 percent of steel production in the country, with this share set to increase in the coming years. U.S. EAFs use mostly scrap mixed with 20-40 percent from iron ore-derived “virgin iron” sources. “Virgin iron” is typically pig iron from BFs and “direct reduced iron” (DRI), which is sometimes sold in the form of “hot briquetted iron” (HBI). A large part of the steel produced in the U.S. is automotive sheet, which has stringent chemistry requirements. As scrap typically has higher levels of impurities that have a negative impact on the steel quality, so-called “virgin iron” must be combined with the scrap in order to maintain the physical properties required to produce high-quality steel. Therefore, expanding EAF capacity in the U.S. is likely to result in higher requirements for DRI and HBI.

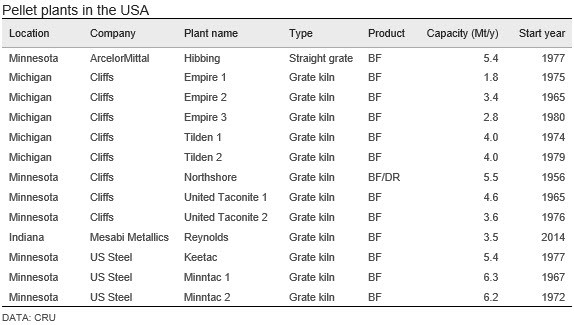

Most U.S. DRI/HBI production is based in the southern states of Louisiana and Texas, near the coast and in close proximity to natural gas supplies. Nucor and Voestalpine both operate DRI plants that import DR pellets primarily from Brazil, Sweden and Canada. However, with the EAF market expanding around the Great Lakes, there is now potential for rising HBI and DRI consumption in this area. Operations located around the Great Lakes will have a shipping advantage over imports or shipments from the southern part of the country. Hence, there have been several new developments in this sector.

Cliffs has led the way, making significant DRI investments in order to capitalize and potentially monopolize this emerging market. A $90 million pellet plant upgrade in Silver Bay, Minn., and an $830 million DRI facility under construction in Toledo, Ohio, form the basis of this venture. The upgraded pellet plant was completed in August 2019 and is currently producing and stockpiling DR pellets, ready for shipping to the Toledo plant that will be completed by the mid-2020s.

The upgraded DR pellet plant has a nameplate capacity of 3.5 Mt/y, with 2.7-2.8 Mt/y reserved for the Toledo plant. This potentially leaves up to 0.8 Mt of DR pellets that could be sold elsewhere. In a recent earnings call, Cliffs announced they would prefer not to sell this product to nearby competitors, but instead look to sell to legacy customers such as ArcelorMittal (AM) in Canada and consumers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. However, given the considerable cost of exporting from the Great Lakes and our current forecast for the DR pellet premium, we do not believe this is sustainable in a balanced seaborne pellet market. Hence, it is more likely that Cliffs will avoid operating the DR pellet plant at full capacity and will only produce the 2.7 Mt/y of DR pellets that its Toledo plant requires.

When the Toledo plant is up and running, Cliffs will sell HBI domestically. The HBI will have a freight advantage over Russian and Venezuelan imports as the product will not need to navigate the St. Lawrence Seaway or Mississippi River to U.S. consumers. North Star BlueScope in Ohio is contracted to be a large customer of Toledo HBI, with just-in-time shipments arriving 62 km by truck—providing a much cheaper transport outlay compared with the shipping and duty costs for imported iron.

In the medium-term, CRU anticipates that, in the U.S., there will be some growth in EAF production, which will lift DRI production. This provides an opportunity for iron ore producers in the U.S. to expand production by developing DR pelletizing facilities to supply DRI plants. So far, Cliffs is the only U.S. iron ore producer to enter this market as high production costs and uncertainty of high-quality DR pellets are making further investments uncertain.

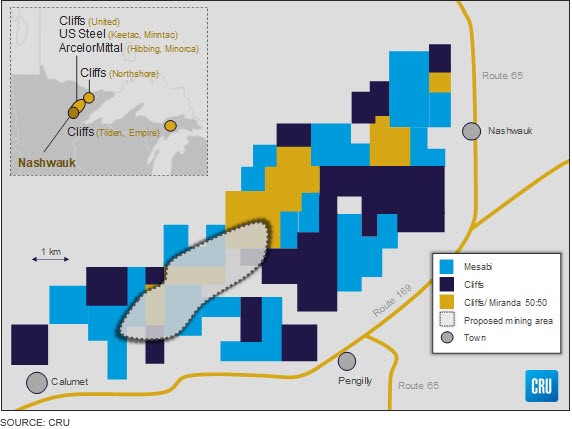

Nashwauk, a Long and Complicated Story

Despite the optimism surrounding DRI production in the U.S., the iron grade required to produce low-silica (<2 percent) DR pellets is not found throughout the U.S. iron ranges. Apart from Northshore, the only other site in the U.S. capable of mining iron at the grade required for DR pellets is the ill-fated Nashwauk project, near Hibbing in the Mesabi Range. The site has long been slated for iron ore production. However, Cliffs has made no secret of their intentions to buy up the relevant permits and construct another DRI plant there, despite a series of ongoing legal battles.

In 2007, India-based Essar Steel’s subsidiary in Minnesota first bought the Nashwauk site and started a costly and haphazard mine construction project, eventually going bankrupt in 2016, leaving several structures abandoned. Cliffs wanted the site for a new DRI plant; however, they lost the bankruptcy bid to a U.S.-based entrepreneur, who subsequently withdrew from the project after his efforts fell flat amid missed deadlines and a lack of investment. During this chaos, Cliffs bought critical mine land surrounding the site, isolating the Nashwauk project and accusing those accessing the site of trespassing. The Nashwauk site is now owned by Mesabi Metallics, which has received capital from Essar Steel. However, the state of Minnesota has moved to debar Essar from doing business in the state. Essar claims that they have additional funding from Swiss investors and Canadian steelmaker Stelco, but the project is stalled due to the debarment of Essar. In the meantime, there have been several court cases between the Minnesota state government natural resources department, Mesabi Metallics, Essar and Cliffs as to who owns the rights to use and access the site.

There would appear to be several outcomes that are likely to result from the complex situation at Nashwauk. Either Mesabi Metallics will restructure to remove direct Essar investment and set up a taconite plant with alternative investors, or Cliffs will acquire the permits to the site and construct another HBI plant sometime in the future. An outside possibility is that ArcelorMittal might make a move to acquire the permits and mine taconite at the site to feed their U.S. blast furnaces.

It seems unlikely that Cliffs will approve another large DRI capital investment so soon after the Toledo plant opening, even if they were to get the Nashwauk permits. The company is currently undergoing a large stock buyback and debt reduction as part of a restructure, after being on the brink of bankruptcy in 2015, and so the company is likely playing a long game for the Nashwauk permits.

ArcelorMittal took over the mine operation at the Hibbing mine it co-owns with Cliffs and U.S. Steel in August 2019 and production there is reaching a critical stage. A decision needs to be made whether to mine the ore body on the other side of the highway, press deeper into the existing pit or move west towards the permit boundary with U.S. Steel’s Keewatin property. Regardless, extra U.S. iron ore capacity provided by Nashwauk would ensure pellet supply for AM’s blast furnaces at Indiana Harbor on Lake Michigan. Moreover, ArcelorMittal is nearing a takeover of Essar Steel suggesting that the Essar investors might go in with ArcelorMittal or completely back out. The situation now is gridlocked and all these options remain open.

Iron Ore Producers Still in the Hands of Local Steelmakers

Recent price and margin fluctuations in the steel market have shaken up the U.S. iron ore industry. In the short term, U.S. Steel’s BF production cuts will make it difficult for the company to maintain current levels of iron ore production. However, increases in EAF production have developed a new opportunity in DR pellet production. We do not expect any further investments in new BF capacities in the medium term, which will limit the upside for U.S. iron ore production. Although high iron ore prices have generated a wave of interest in new projects in other parts of the world, such investments in the U.S. are typically hindered by an inability to export from the Great Lakes at low costs. The U.S. iron ore market is thus dependent on the North American steel industry, and any increase or decrease in BF production has a substantial effect on the country’s iron ore output. Recent BF closures and increasing DRI production will force some adjustments in U.S. iron ore supply, but the fundamental picture remains the same—U.S. iron ore production will remain isolated from the seaborne market and production is expected to follow the same trend as BF production around the Great Lakes. The magnitude of DRI investments is not great enough to result in significant changes to domestic iron ore production.

Analysis by Daniel Keogh and Adam Smith