Market Data

November 15, 2015

Are AD/CVD Duties Effective?

Written by Sandy Williams

Trade protection is a driving concern for the U.S. steel industry that has seen prices and domestic demand plummet as low priced steel imports flooded American shores. Steel mills, unions and legislators have lobbied for stronger enforcement of trade policies and the additional safeguards from dumped and subsidized imports and currency manipulation.

Currently the focus is on three major antidumping and countervailing duty cases affecting the flat rolled steel industry: hot rolled, cold rolled and corrosion resistant steels. The preliminary decisions on these cases are due in December and January, and one decision on corrosion resistant steel the countervailing duty preliminary decision has already come out; but the filing of the cases has had a milder impact on the prices of these products than many expected. The question is then: do AD/CVD filings actually work?

History of Steel Trade in the U.S.

Before the 1960s, the U.S. steel industry was a major exporter of steel products, but during the 60s the trade balance shifted the industry to a net importer. According to an in-depth study by Blonigen, Liebman, and Wilson, Trade Policy and Market Power: The Case of the U.S. Steel Industry* (2007), numerous factors contributed to the toppling of the U.S. steel industry as a globally preeminent player and a primary exporter.

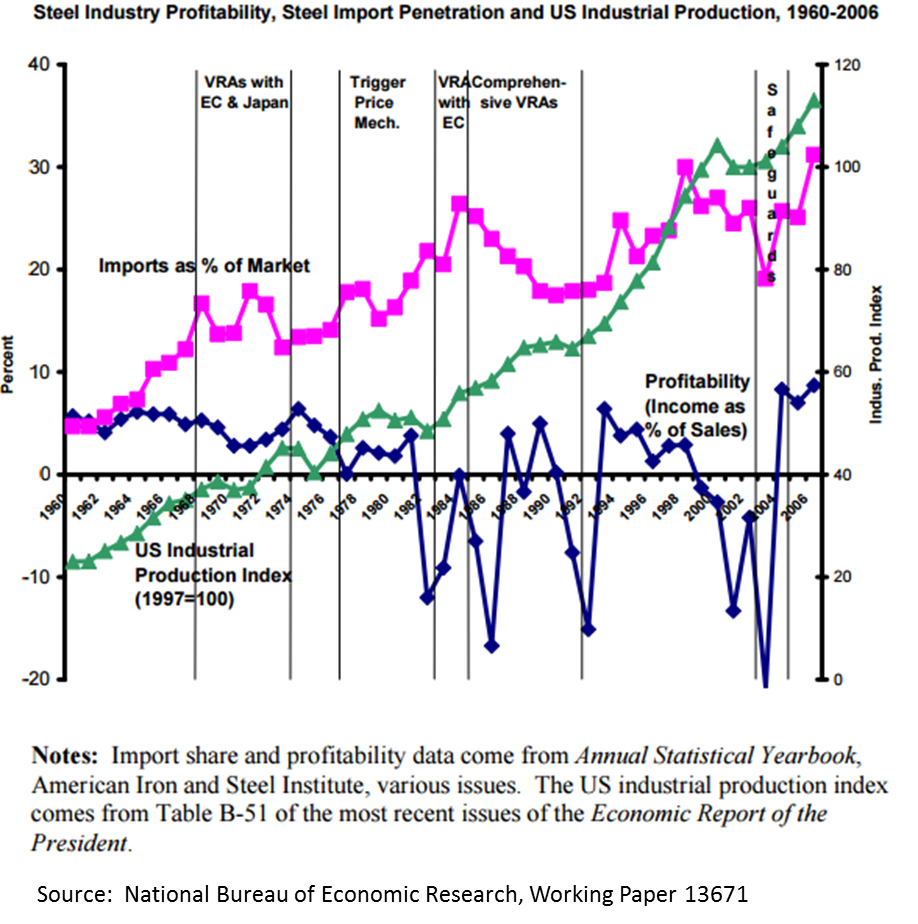

The factors included: 1) a lengthy steel strike in 1959 that prompted downstream users to seek imported sources of steel out of necessity; 2) more efficient and modern subsidized steel operations in Europe and Japan, a result of rebuilding their industries with modern equipment following World War II; 3) discovery of large foreign iron ore deposits; and 4) a strong U.S. dollar. These factors led to import market share increasing from 4.7 percent to 16.7 percent between 1960 and 1968.

Steel makers pressured the government to negotiate a Voluntary Restraint Agreement (VRA) with Japan and Europe in 1969. When this first VRA expired in 1974 it led to a surge in imports, resulting in increased AD and CVD petitions and calls for renewed trade restrictions. To counter a proliferation of filings, a Trigger Price Mechanism (TPM) was implemented in 1977 during the Carter administration in which the industry agreed to refrain from AD/CVD petitions as long as import prices did not fall below Japanese production costs, plus an 8 percent profit margin (then the norm in antidumping cases for setting foreign market values). At the time, Japan was the world’s lowest cost producer of steel.

The TPM was renewed in 1980 but the steel industry argued the policy did not provide enough protection from European imports. The program ended in 1981 and over 100 AD/CVD petitions were filed in January 1982 against primarily European steel producers covering a wide range of steel products. To avoid trade disputes, another VRA agreement was implemented in October 1982 covering steel products from Europe, holding them to 5.5 percent of the U.S. market.

The 1982 VRA largely failed due to a strong U.S. dollar and imports of steel products through other countries. AD/CVD filings shot up in 1984 and led to the “Section 201 Escape Clause” filing. That case was resolved by a second round of VRAs for all finished steel products that limited total import market share to about 18.4 percent. The VRAs were set to expire in 1989—the new Bush Administration renewed the VRAs for two and a half years (not the five years the industry wanted), due to opposition by steel consumers. By 1992, the VRAs expired permanently, as no countries wanted to maintain them. That year the industry filed another surge of AD/CVD petitions.

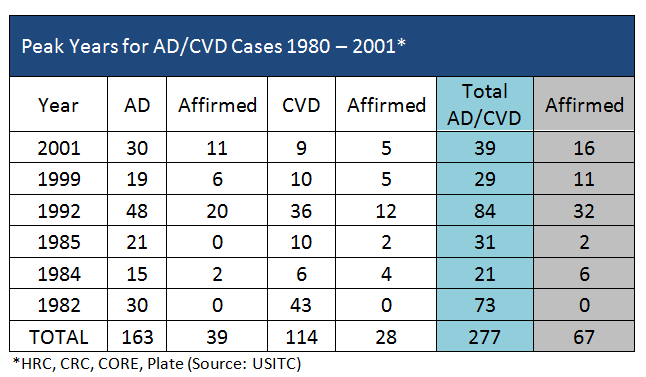

In mid-1992, 84 antidumping and countervailing duty filings were filed on cut to length steel plate, hot rolled, cold rolled and corrosion resistant sheet steel from 21 countries. By time the final determinations were issued in 1993, only 32 of those filings were in the affirmative. According to Blonigen, et al., mini-mill competition (which was just beginning to make inroads in flat products) was blamed for perceived injury rather than imports in several of the cases.

AD/CVD filings fell off in the 1990s as the steel industry went through a “renaissance” period due to a strong economy and modernization of facilities.

By the end of the decade currency crises in Russia and East Asia led to a new surge of steel imports into the U.S. market. The 1998 recession in Asia (the Asian financial crisis) caused steel to move from Asia to the healthiest market in the world, the U.S. This import surge helped put many American steel companies into bankruptcy

The import crisis led to a new Safeguard filing in 2001. President George W. Bush granted most of the petitions and imposed safeguard tariffs of 30 percent on most flat rolled products. Canada and Mexico were excluded from the tariffs along with less-developed countries and downstream industries succeeded in lobbying for numerous exceptions on products not available domestically. In 2003, the World Trade Organization ruled that the U.S. safeguards violated international agreements negotiated in the 1990s (the Uruguay Round) and the tariffs were terminated.

The last ten years saw another damaging recession for the steel industry and a resurgence of protectionism, including an increase in AD/CVD filings.

Do AD/CVD filings work?

According to the Blonigen, et al. study, the simple answer is not really. Steel import share increased from 5 percent in the early 1960s to over 30 percent in the early 2000s. The study did not find a correlation between steel firm profitability and falling import share, and found it was actually a zero or negative correlation. The study was based on demand, import supply, U.S. pricing and annual product data for the period 1980 through 2006.

Blonigen, et al. concluded that although most protection programs had at least moderate impact on reducing imports, only the VRA in the late 1980s gave the steel industry the ability to significantly price above marginal cost. The study found that VRAs were more effective that AD/CVD rulings due to the practice of diverting steel imports through other countries to avoid duties (a practice that steel mills are currently seeking to address.)

SMU looked at past AD/CVD filings for hot rolled, cold rolled, and corrosion resistant steel (galvanized, Galvalume) to see what decisions and duties were levied by the Department of Commerce.

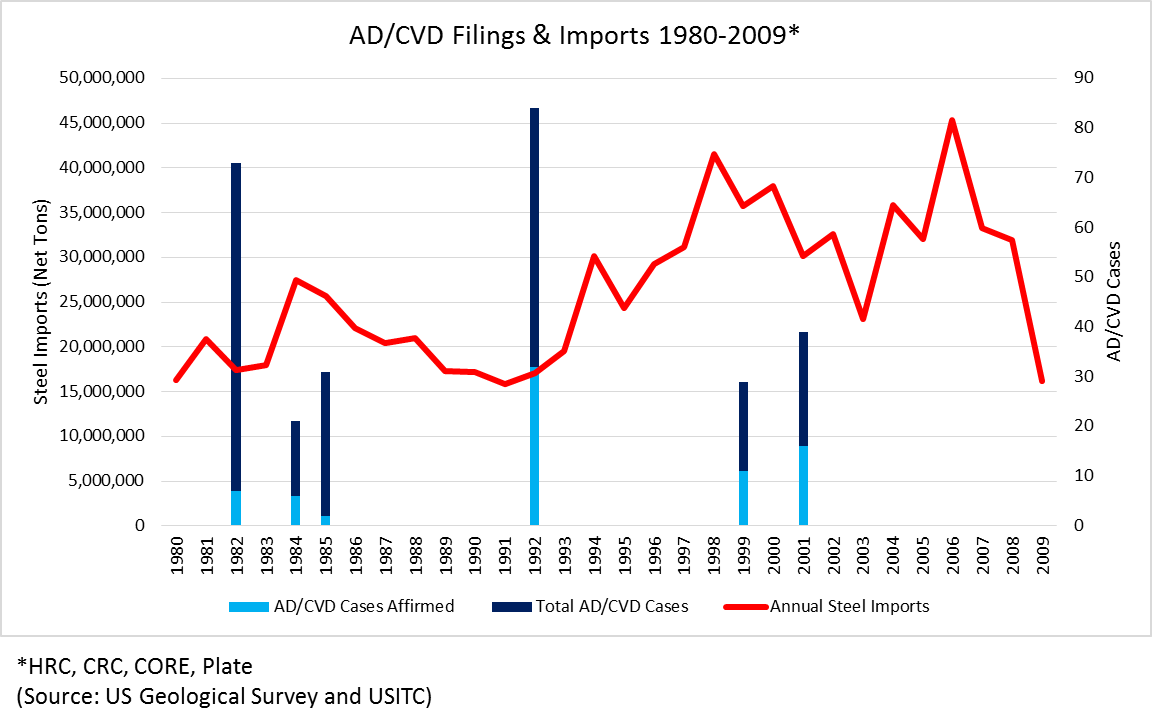

There were six peak years for AD/CVD filings during the period 1980 to 2007. Although, a wide range of steel products were included in those years, we looked specifically at AD/CVD cases for hot-rolled, cold-rolled, corrosion resistant flat rolled steel and steel plate. In 1982, 73 AD/CVD cases were filed, of those just seven CVD cases received an affirmative determination, all the rest were either terminated because of VRAs or given a negative determination. In the six years of AD/CVD cases reviewed for the products listed above, 277 AD/CVD filings resulted in just 74 affirmative decisions. Although affirmative determinations were low, keep in mind that a number of cases were resolved (terminated) because they were replace by VRA quotas.

However, when you compare filings for the four products to steel import statistics you can see that imports, in general, continued to climb despite AD/CVD filings. Only in the mid-1980s did there appear to be a noticeable drop in import levels, which was also when the VRAs pursuant to the Section 201 Escape Clause cases were implemented.

In a policy brief, Steel: Big Problems, Better Solutions, by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, authors Hufbauer and Goodrich wrote that most trade solutions, or import barriers, favored by the steel industry have major flaws:

“Import barriers are not very good at getting foreign governments to correct their own market distortions. This has been experienced not only by the steel industry, but also by numerous agricultural commodities (dairy, wheat, and corn), telecommunications, civil aviation, and financial services. In very few of these industries have US import barriers persuaded other countries to create more competitive markets. Instead, trade barriers have a way of inspiring “me-too” restrictions abroad, increasing the number of years (or decades) it takes for the industry to adjust worldwide.”

The current steel exporter driving U.S. steel manufacturers to seek stronger trade remedies, of course, is China. Chinese exports were up 26.5 percent in the first eight months of 2015, reaching 7.87 million tonnes.

US Steel CEO Mario Longhi, a leader in the fight for a level playing field for the steel industry, says the challenge of steel imports from China is growing.

“We have seen import surges before,” Longhi said in a recent press briefing. “What makes it worse this time is that there is a massive level of overcapacity that has caused an unending supply of steel imports flooding our market with no end in sight unless the government helps stop it.”

Trade attorney, Lewis Leibowitz says Longhi has a point. “In the 1980s, China was a non-factor in the market. Now they produce half the steel in the world, and nearly 10 times the US production. This latest episode is about dealing with China. But the US alone can’t really change anything. Chinese capacity has to be shut down, which would cause a lot of headaches in China.”

Legislative changes to trade remedy laws have recently been passed. The changes affect the details of trade law enforcement but are not considered to be major. Provisions in the recent Trade Adjustment Assistance program legislation strengthened the Department of Commerce’s authority to impose punitive duties for uncooperative foreign respondents and to make an affirmative “material injury” determination easier. At the same time, the Trans Pacific Partnership agreement is being reviewed around the world and would reduce international barriers to trade and phase out numerous import tariffs. It would also address allegations of “currency manipulation” but not in a way that would please the US steel industry. TPP has its proponents who applaud trade expansion, and opponents who fear the agreement will threaten domestic production and employment.

There is no easy solution for staying competitive in an expanding global market that includes emerging economies that have lower labor, production and energy costs and, in some cases, industries that are subsidized by governments.

The most recent filings on cold rolled, hot rolled and CORE products are thus far not slowing imports to the degree expected by the industry and having little upward effect on steel prices. Third quarter earnings reports show a lack of optimism for an upturn in the remainder of 2015, although, as determinations are made in the AD/CVD cases, there is hope that it will lead to an improved supply and pricing situation in 2016.

SMU Note: This article references Blonigen, B., Liebman, B., & Wilson,W. (2007), Trade policy and market power: the case of the U.S. steel industry, (Working Paper 13671), National Bureau of Economic Research; and Hufbaurer, G. & Goodrich B. (2001), Steel: big problems, better solutions (2001), Peterson Institute for International Economics; but there are numerous articles and opinions available on steel industry trade remedies that are available to readers at websites like the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and Heritage Foundation. We also invite you to attend our Leadership Summit in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida in March where trade attorney Lewis Leibowitz will help you to understand both the history and the current trade situation.