Canada

January 30, 2025

CRU: Canada would struggle to re-direct its US steel exports

Written by Matthew Watkins

Would Canada’s steel exports be re-directed if the USA imposed import tariffs against Canadian goods?

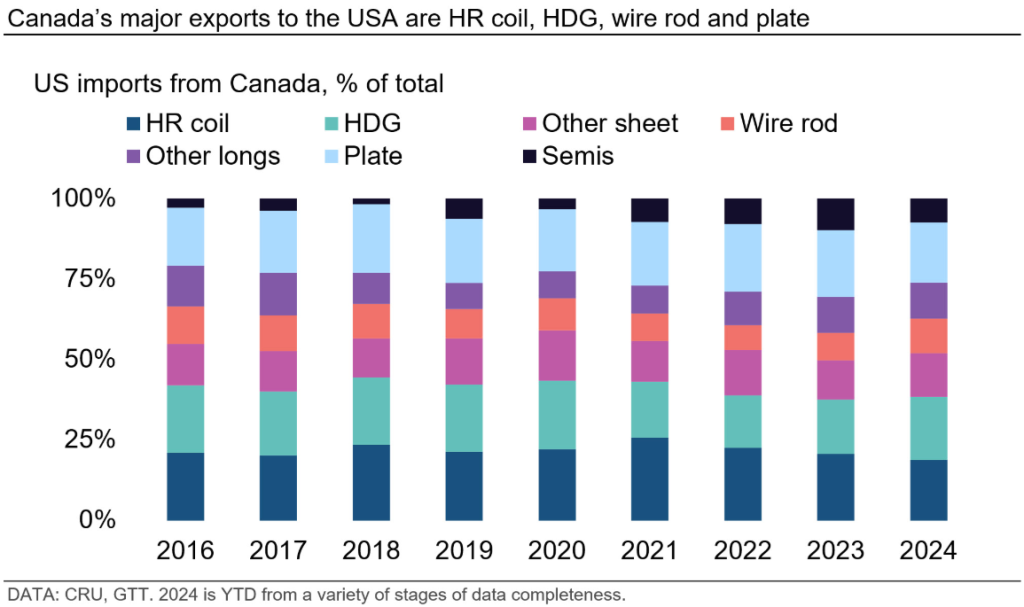

Canada has consistently exported 4–6Mt/y of steel over the past decade or so. This trade flow is overwhelmingly focused on just one destination – the USA. With Mexico receiving the largest amount of the rest, Canada has a tiny exposure to the world outside USMCA, averaging only 150,000 t/y since 2016.

USMCA is option 1 but will cost more or not be big enough

One simple possibility is that exports continue to the US and importers there pay the tariffs. This is likely in the event that the Canadian product is not available in the US (this has been the case with some European steel products, for example) or that even with the tariffs, it remains sufficiently attractive on price, quality, lead time or other grounds. A more heavily tariffed US market could see its market prices increase, which may allow this.

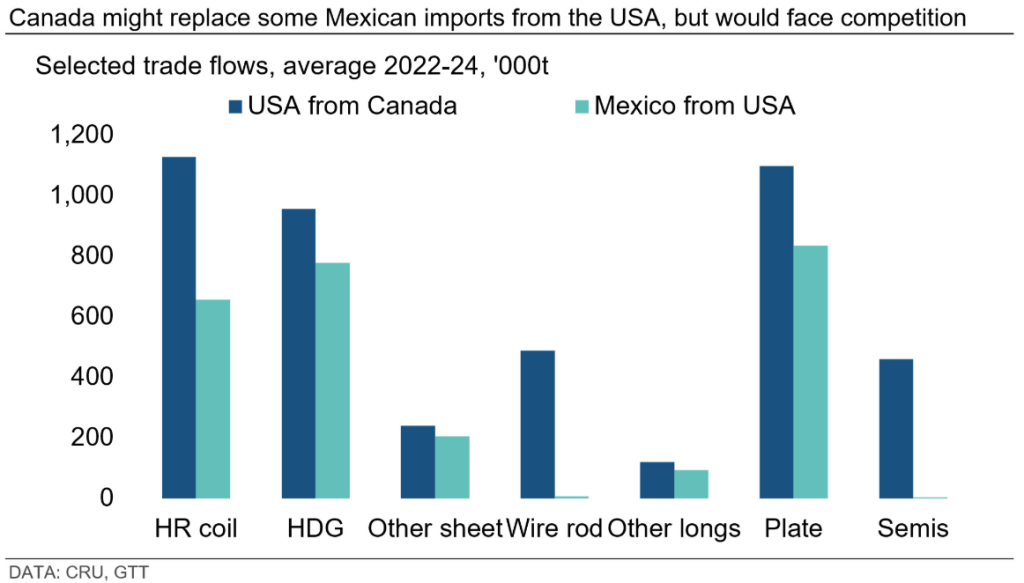

If US-Mexico trade flows are also disrupted by tariffs, Canada could potentially replace steel that Mexico currently imports from the US. This is not a large enough flow to completely solve Canada’s problem, but it could help, noting however that Mexican mills would probably first look to displace their own lost US exports.

Cutting production in Canada is likely to be a last resort but, at least in theory, is a possibility.

New niche export opportunities may exist, but against strong headwinds

Canada’s huge dependency on the local region means there is no pre-existing set of systems for Canadian mills to sell at scale into the global market. In-house export teams and sales relationships are not set up to do this. These could be built, if needed, but would take time and investment, which would probably only be forthcoming if the US market was viewed as structurally limited for an extended period. The more likely scenario – at least for the short term if not beyond – would be to use third-party traders to handle things. This would be easy to arrange.

Logistically, Canadian steel mills are well placed to get steel out of the country. Almost all of them could readily use the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway to get into the Atlantic. Access to Western Europe or Brazil would be very easy. However, shipping west to access Asian markets would probably not be viable. Markets in Africa could be accessible but may not offer an attractive combination of scale and value.

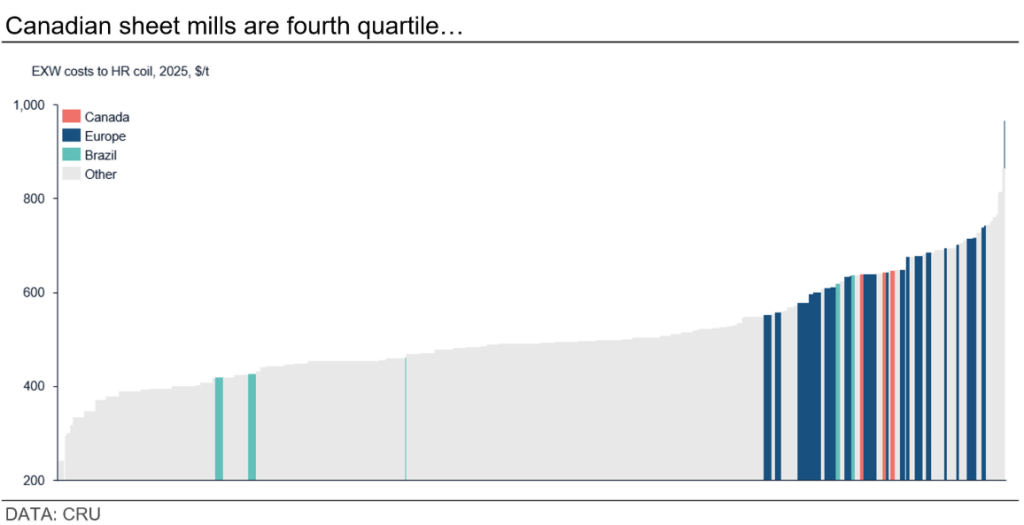

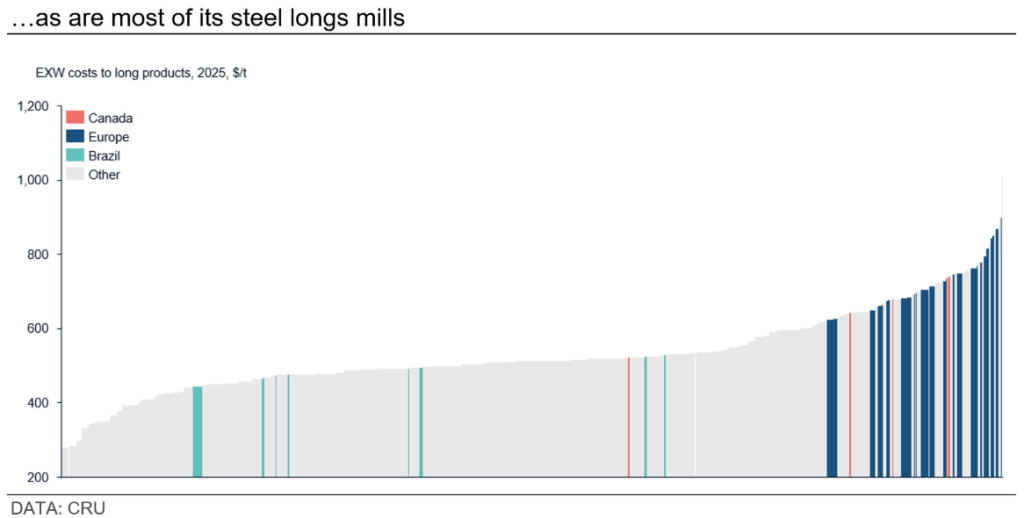

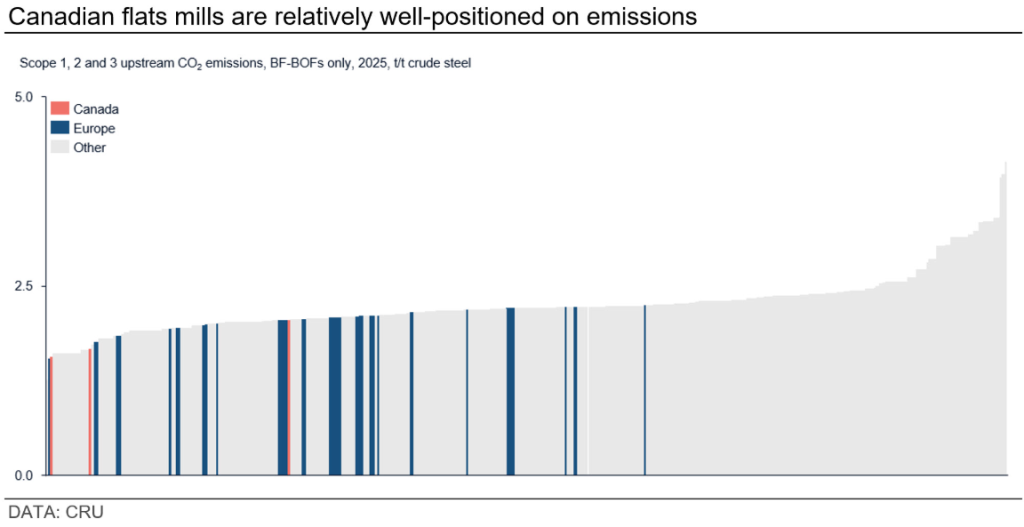

Production costs are high in Canada, and this would limit the economic reach of its mills. The cost curves below show that Canadian mills are almost all fourth-quartile EXW cost assets on the global scale. Competing on costs in Brazil would be tough, to say the least. In Europe the EXW cost position is similar to domestic mills, so although the Canadians would be at a freight disadvantage, the prospect may not be a non-starter if other parts of the value proposition are right.

The experience for European mills over recent years has been that exporting has become broadly unviable, other than for a relatively small volume of high-value products. A high-value niche approach could therefore in principle also work for Canada and help it compete against other lower-cost exporters to Europe. Drawbacks of this approach are that it would compete with domestic high-value mills in Europe and the volume in such markets is inevitably relatively small.

One other niche approach, which could raise buying interest is in the area of low-emission steel. Europe is the likely demand center for such steel for the foreseeable future. Its longs mills are largely already EAF, and relatively low-emission EAFs at that. But its flats mills are almost all BF-BOFs and while they are low-emitting relative to other BF-BOFs, so are the Canadian ones and arguably a little lower.

Most European BF-BOFs have decarbonisation strategies, which will change this emissions curve in the coming years. However, such strategies also exist in Canada. Algoma is switching to EAF; meanwhile some European mills are postponing – though not yet cancelling – their decarbonization investments.

Thus, with careful matching of seller and buyer, there may be some export opportunities in Europe. However, one further factor to consider is that European steel mills would probably seek to block the flow. The clear precedent is its existing safeguard system, which was put in place immediately following Section 232 in the US with the aim of protecting against the perceived threat of re-directed steel. Lobbying for tighter control over imports has ramped up and been quite successful in getting trade barriers imposed. We would expect Europe to try and resist further imports.

Imports could be substituted, but not enough of them

In a recent Community Chat, hosted by Steel Market Update (which is owned by CRU), the former CEO of Stelco Alan Kestenbaum asserted that earlier US imposition of Section 232 tariffs against Canada led to Canadian steel staying in Canada, and US steel staying in the US. He also added that this was profitable for at least the Canadian side. Therefore, along these lines, rather than seeking out alternate export markets a simpler solution may be for Canadian mills to look to substitute imports.

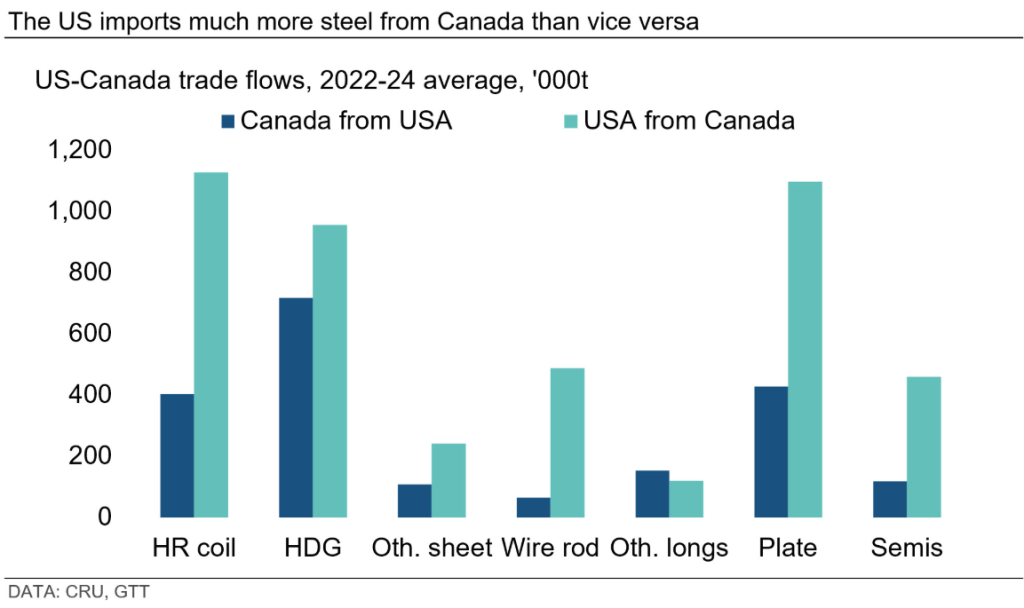

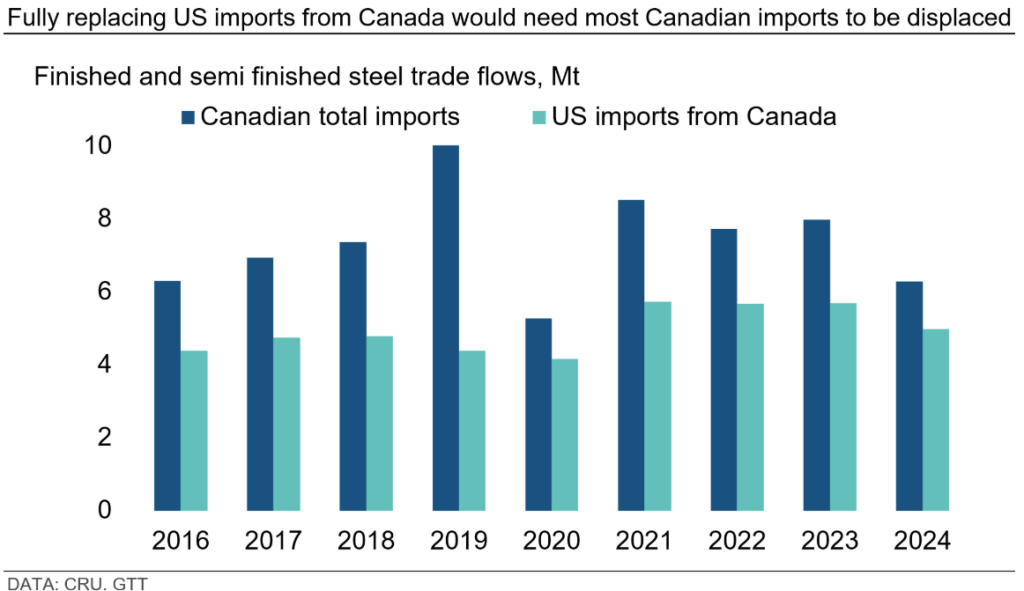

On average from 2022 to 2024, Canadian imports from the US accounted for about 45% of the volumes of Canadian exports to the US. Thus, even if it could achieve 100% substitution of US imports, this would only solve a little less than half the problem.

Other imports would therefore need to be replaced. Canada does import from a range of other origins, but the scale required seems unrealistically large. The export flow to the USA is about 70% of the size of Canada’s total steel imports.

Tariffs remain uncertain

It remains uncertain whether tariffs will be implemented, and so this analysis is a consideration of a theoretical future world. There are a number of Canadian goods exports to the US where domestic substitutes are not readily available; and hence applying tariffs does not confer an obvious advantage to the US. Examples include oil (some US refineries are designed for the Albertan oil sands) and potash. Meanwhile, in the steel industry certain products, such as specific categories of wire rod, are overwhelmingly supplied by Canada. This may suggest that a blanket tariff approach is sub-optimal. Yet in steel as a whole, the US is a net importer from Canada, which may cause the sector to remain a tariff target.

This analysis was first published by CRU. To learn about CRU’s global commodities research and analysis services, visit www.crugroup.com.