Prices

March 19, 2023

Leibowitz: Steel and Aluminum Consumers Pay the Duty Bill

Written by Lewis Leibowitz

The US International Trade Commission issued a report to Congress last week on the impact of the Section 232 import restrictions on steel and aluminum and the tariffs on imports from China under Section 301.

The report catalogued significant injury to downstream industries. Namely, those that use steel or aluminum in manufacturing. The losses were aggravated by the fact that American consumers (both industrial and individual) paid almost all the tariffs and quota rents. The economic burden of the Section 232 measures therefore falls on US consumers, not on foreign producers.

The last time the US put broad tariffs on imported steel was in 2002-03. A recent study analyzed the effects of those steel tariffs. The study found that the Safeguard tariffs (30% on most steel products) significantly depressed exports of steel-containing products. They also pinched domestic production and profits in downstream industries more generally. Production of steel-containing projects declined in the United States, and the decline lasted much longer than the actual tariffs did. Depressive effects on production persisted at least to 2009.

A similar effect on downstream manufacturing may be expected from the Section 232 (and 301) tariffs. It stands to reason that this would happen. In steel, for example, industries that use steel in manufacturing (transportation, construction, capital equipment) are much larger than steel production. Tariffs on an important commodity like steel can be a sledgehammer for downstream customers, reducing their efficiency and profitability. The harm to downstream manufacturing is much greater than the benefit to steel producers.

A 2003 study by Laura Baughman of the Trade Partnership issued in 2003 (full disclosure: I was involved in the preparation of the study) found that steel-using industries in the United States lost about 200,000 jobs during the first year of the Safeguard tariffs. That is more jobs than existed in the steel production industry at that time.

It is easy to see why the effects can last long after the tariffs were withdrawn in 2003. Downstream manufacturers must make decisions on a global basis. If products are made overseas using steel that costs less than in the US, downstream manufacturers will move their production out of the United States. The longer the tariffs last, the more serious their damage will be on downstream industries. And since downstream industries collectively have many more jobs, the negative employment effects on downstream users will have much more impact than employment increases in steel or aluminum will help.

Section 232 tariffs can be avoided by obtaining an exclusion. In steel and aluminum, about 211,000 exclusions have been approved since June 2019. But approved exclusions are not that easy to get, especially if a domestic company objects to the request. Some 88,000 requests have been denied.

Applying approved exclusions to actual Customs entries can also be tricky. More than a few companies have found that approved exclusions may not be applied to entries by Customs due to problems with quantities, country issues, and Customs classification.

With all the protective tariffs being put in place, it might be tempting to conclude that producers would make more profits and increase production and product quality. That has happened to some degree. In steel for example, companies are building new factories.

When these new plants open, they will, to some degree, replace old mills. How much the new mills will add to US capacity is therefore not certain. But the new mills are likely to be cleaner and more efficient (and require fewer workers) than the old ones. So the economic impact of these tariffs and quotas on the US economy looks much greater on the negative side (hurting steel-using manufacturers) than on the positive side (helping steel producers).

The idea that the United States market for steel, aluminum, or any other globally traded commodity can be isolated from global economic forces is fanciful. Economic conditions in China, India, or South Africa will affect the United States. Market prices in in the US will affect and be affected by prices in other markets.

If the United States becomes an island of high prices for steel compared to other major markets, demand for steel in the US will decline as production moves to other markets. Until the latest round of protection, government action on steel has generally been temporary. For example, the Safeguard tariffs on steel lasted only 18 months. Safeguard import measures can last no longer than eight years.

But the Section 232 tariffs are different. Unlike Safeguard measures, there is no required end date for these measures. Companies that used to make downstream products in the US will shift production overseas (or cede their markets to foreign companies). The long-term pressures of isolating the US market could cause domestic demand for steel in manufacturing to decline as steel users look for new manufacturing locations and for raw materials other than steel.

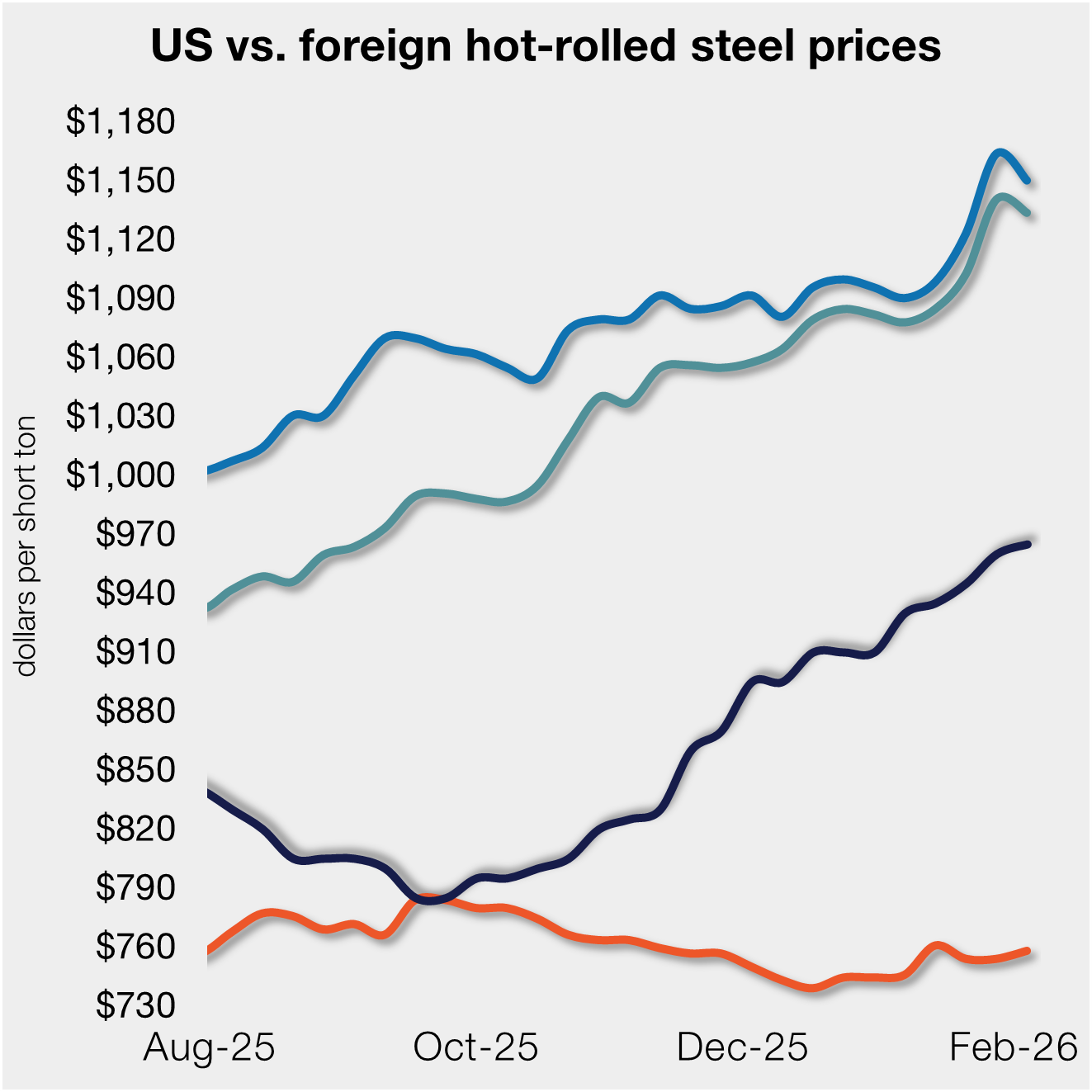

Steel companies have enjoyed brief periods of prosperity since the 2018 measures were put in place. In 2021, steel prices skyrocketed, then came down to earth. A muted version of the same seems to be happening now. Steel prices are now on the rise. Market forces will eventually bring them back down.

When prices rise, customers tend to slow their purchases. As they come down, purchases will increase. The long-term trends will continue. Steel intensity in the US economy will likely decline, as happens in the most developed industrial economies. Government action will affect demand at the edges, but the long-term trends are likely to continue.

While political considerations are driving the current policies, economic reality will drive changes in those measures over the long term.

Lewis Leibowitz

The Law Office of Lewis E. Leibowitz

5335 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Suite 440

Washington, D.C. 20015

Phone: (202) 617-2675

Mobile: (202) 250-1551

E-mail: lewis.leibowitz@lellawoffice.com