Market Data

June 10, 2022

CRU Energy Prices: How Much More Pain Is To Come?

Written by Alex Tuckett

By CRU Principal Economist Alex Tuckett, from CRU’s Global Economic Outlook

Energy costs for consumers – in the form of utility bills and the cost of filling a car – have risen sharply, but not as sharply as the cost of crude oil and natural gas. But this doesn’t necessarily mean a lot more pain for consumers to come – unless there are further increases in wholesale prices. The manufacturing sector, on the other hand, has faced a fiercer rise in energy costs, and this will continue to feed through the supply chain for some time, keeping CPI inflation elevated.

Energy Prices Have Pushed Up CPI Inflation

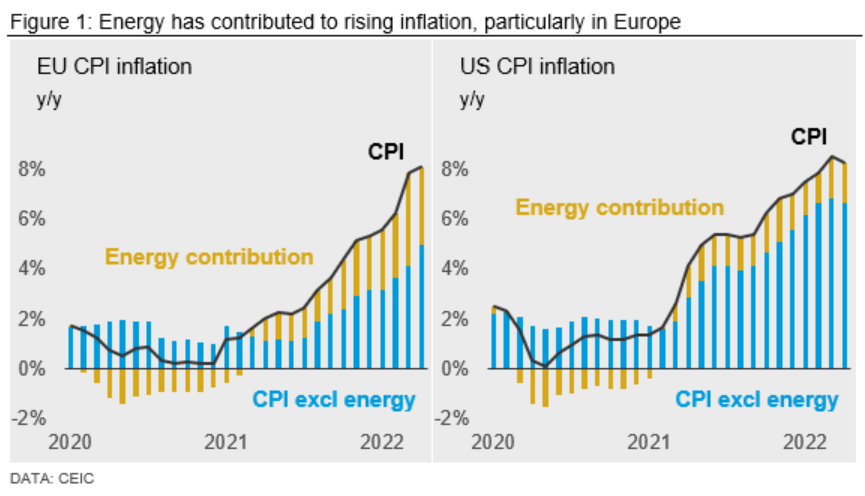

Wholesale energy prices for oil and gas have soared in the past year. These increases have helped to push consumer price inflation (CPI) to multi-decade highs in the US and Europe. In April CPI inflation was 8.1% in the EU, of which 3.1ppt was accounted for by energy. Inflation was 8.3% year-on-year (YoY) in the US, of which 1.6ppt was accounted for by energy. These dynamics are displayed below in Figure 1.

How Much More Is To Come?

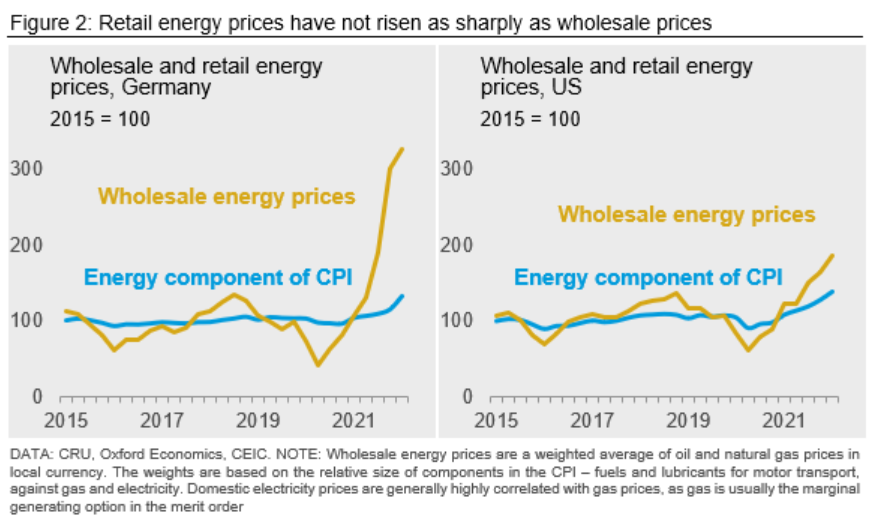

The energy component of the CPI index has increased by 30.3% in the EU in the year to April, and 35.6% in the US. While large, these increases have been much more modest than the equivalent rises in wholesale spot energy prices. For example, Brent crude in April averaged $107.1/bbl, 60% higher than April 2021. Over the same period, the price of natural gas in the US (Henry Hub) increased by 148%, while the price of natural gas in Europe (TTF) increased by a shocking 327%. Figure 1 illustrates this graphically, showing the energy component of CPI for Germany and for the US, compared to a weighted average of wholesale oil and gas prices (in dollar terms for the US, euro terms for Germany). The picture for France, Italy, Spain, and the UK is similar to Germany.

Figure 2 suggests there is scope for retail energy prices to rise much further in Europe, even if there are no further increases in wholesale spot energy prices. However, retail prices need not move one-for-one with wholesale spot prices. The wholesale cost of energy represents only one part of the final cost paid by consumers for petrol, electricity, or gas for home heating and cooking. Costs in other parts of the value chain – for instance, refining and transmission – will be much more stable.

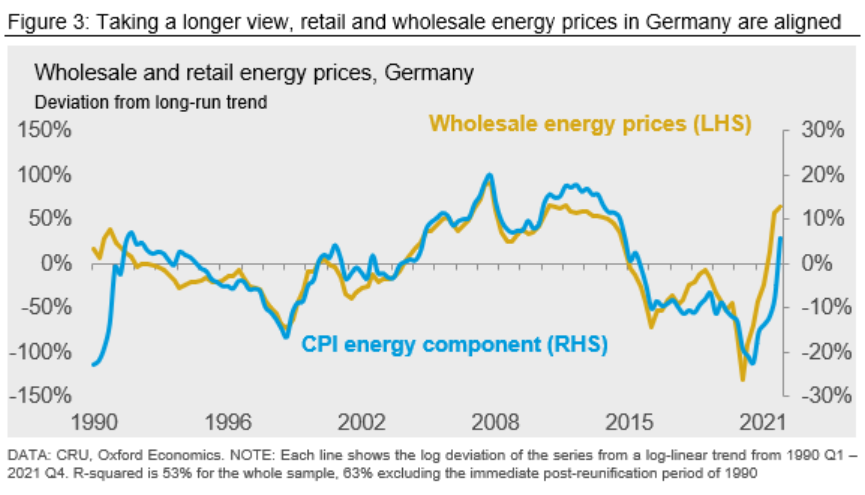

Because of this, it is useful to look at the data over a longer horizon. Figure 3 does this for Germany. It shows the deviation in the wholesale energy index in Figure 2 from its long-run time trend, plotted against the energy component of the CPI (also de-trended). Looking at the data this way, three things become clear:

• The volatility of wholesale spot prices is massively higher than retail prices (note the different scales on each y-axis).

• When this difference in volatility is accounted for, wholesale and retail energy prices have moved quite closely together over the past 30 years.

• Based on the historical relationship, retail energy prices do need to rise further to ‘catch up’ with wholesale prices – but only by around 7%.

Although the historical correlation is not quite as tight, broadly the picture is similar for other major Eurozone economies and for the US. In fact, retail energy prices in the US, France, Spain, and Italy are slightly above where they ‘should’ be based on the historical relationship with wholesale energy prices. The exception is the UK, where retail prices still have around 16% to catch up with wholesale prices. However, the historical relationship fits less closely for the UK (the R-squared coefficient is 33%, against 53% for Germany).

Based on this analysis, we do not expect energy to continue to contribute to inflation in Europe and the US at the same rate as over the past year. Retail energy prices will rise further, but not as sharply. Of course, this depends on wholesale energy prices avoiding a further spike upwards.

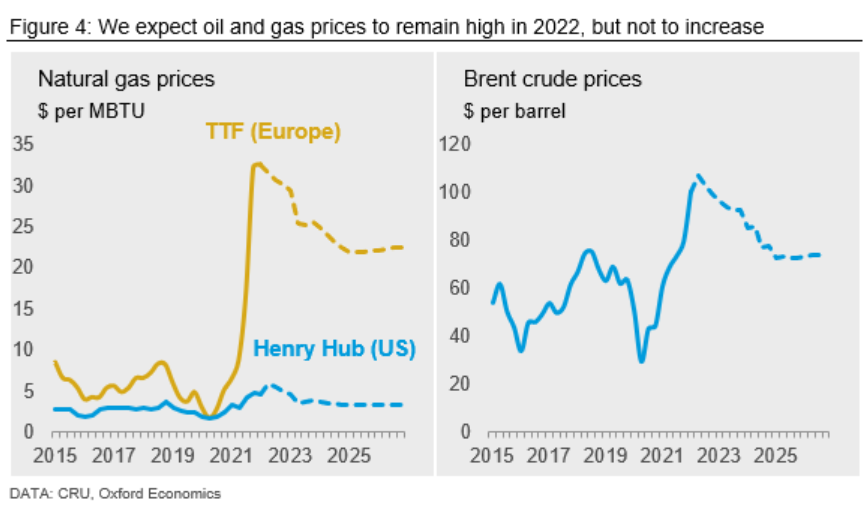

Our forecast is for European gas prices to remain above $30/MBTU for the rest of 2022, as the continuing war in Ukraine keeps the risk premium high (Figure 4, left-hand side). Thereafter, prices begin to fall as Europe can diversify away from Russian supplies, but prices remain well above the pre-2021 level.

Oil prices recently spiked as the EU finally announced a phased-in (and partial) embargo on Russian oil. With inventories low and demand in China recovering, we expect prices to remain above $100/bbl for most of 2022.

A further spike higher in either oil or gas prices – for example, caused by a decision by Russia to stop pumping gas to major European economies, or by the EU to stop buying it – would lead to further increases in retail energy prices and CPI. However, we do not expect the increases in wholesale prices that have already occurred to lead to substantial further upward pressures on CPI.

Retail Prices Are Not the Whole Story

Rising energy costs matter because they squeeze consumer spending power, leaving households with less money to spend on other goods and services. The upward pressure on CPI may also lead to tighter monetary policy, further squeezing spending. However, energy prices also matter for firms, particularly in energy-intensive parts of the industrial sector such as aluminum, steel, and fertilizers.

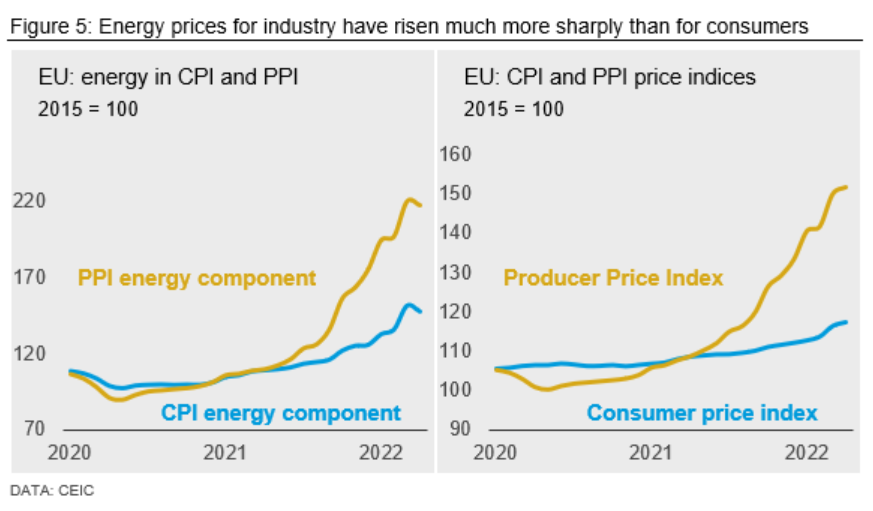

The regulatory framework in most European countries shields households from feeling the full impact of higher energy prices at least in the short term. In addition, governments in Europe have introduced several exceptional fiscal or regulatory support measures for households. Manufacturers enjoy less regulatory protection. The cost of energy to European industry – as measured in the producer price index (PPI) – has risen far more sharply than the retail costs measured in the CPI (Figure 5, left-hand side). Energy prices for industry have also risen faster in the US than for consumers, though the gap is less dramatic.

Many industrial energy users will protect themselves through long-term energy contracts or hedging. But those buying energy on the spot market have been exposed to the full force of price increases, leading to widespread plant closures in the aluminum sector. If energy prices in spot markets remain high, more producers will share in the pain as fixed-price contracts and hedges expire.

Furthermore, higher energy costs faced by firms have contributed to surging PPI inflation (Figure 5, right-hand side). The PPI index for the EU was up 39.7% y/y in April; the comparable figure in the US was 21.5%. These increases in ‘factory gate’ costs will put further upward pressure on the non-energy components of CPI. Partly for this reason, we expect inflation in both the EU and the US to remain high for the rest of the year, averaging 5.7% in the EU for Q4 and 6.8% for the US.

This article was originally published on June 9 by CRU, SMU’s parent company.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com