Market Data

February 11, 2022

CRU: U.S.-China Relations—Stuck in the Middle with You

Written by CRU Americas

By CRU Economist Veronika Akhmadieva and CRU Senior China Economist Henry Hao from CRU’s Global Economic Outlook, Feb. 14

The last day of 2021 marked the end of the two-year period during which China agreed to increase imports of certain goods and services from the U.S. by a combined $200 billion. These targets have been missed by a wide margin. In this Insight we discuss what could come next for U.S.-China trade relations. It is possible that trade relations will either improve or get worse over the next year – but we think the U.S. political landscape means the most likely outcome is that they will remain “stuck” where they are, without significant new tariffs being introduced but also without existing ones being rolled back.

The U.S. has the largest trade deficit in the world and over 65% of it is accounted for by the bilateral deficit with China. During the Trump administration, tensions over trade turned into the imposition of wide-ranging tariffs on Chinese imports, an escalating trade war, and eventually an ambitious set of targets for China to buy more in the “Phase One” bilateral trade agreement.

The U.S. and China are the two largest economies in the world. Over the past decade, they have contributed nearly half of world economic growth. Given their size, and the complexity of global value chains, tariffs and other trade disputes between them can have knock-on effects on other economies.

China Misses Its ‘Phase One’ Targets to Buy More American Imports

The Economic and Trade Agreement between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China: Phase One came into force on Feb. 14, 2020, and was meant to help narrow down the U.S. trade deficit with China, and eventually lead to the removal of tariffs. However, two years later the legal agreement proved to be insufficient to normalize the trade relationship between the world’s two largest economies.

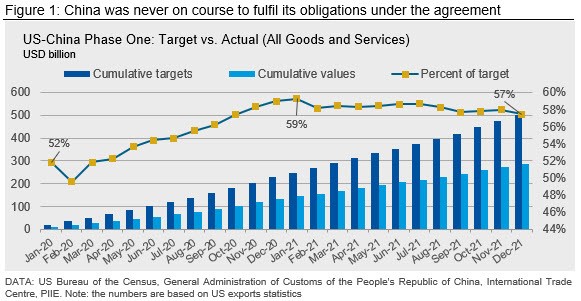

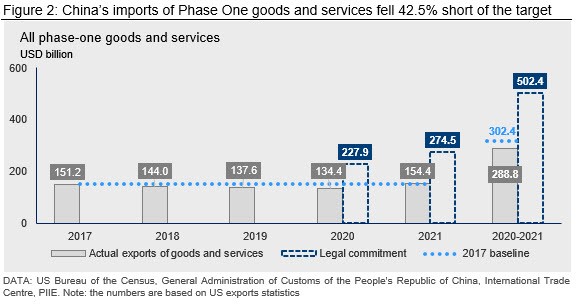

Under the Phase One deal, China promised to import dramatically more from the U.S. by buying an additional $200 billion in goods and services in 2020 and 2021, compared with 2017 levels. However, China met less than 60% of its purchasing goal (Figure 1). Overall Chinese imports of goods and services fell 42.5% short of the target, not even reaching the $302.4 billion China would have imported if it maintained its 2017 level of U.S. imports during this two-year period (Figure 2). In other words, China failed to import any of the additional $200 billion of U.S. exports that it was supposed to purchase according to this agreement.

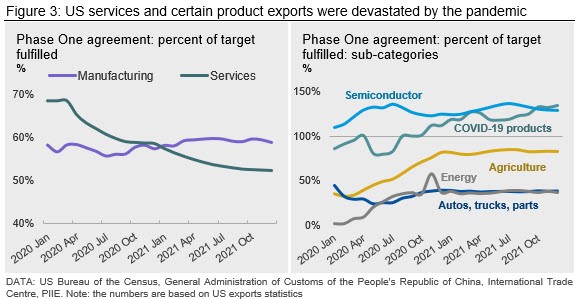

Progress towards the targets has varied greatly across different categories (Figure 3). Covid-19 and the consequent lockdowns and mobility restrictions made it virtually impossible for China to fulfill its obligations for imports of services such as business and education-related travel as well as tourism. Given that services were the second largest part of the agreement, it means that China would have struggled to meet the final target regardless. In contrast, China came much closer to meeting its commitments to buy agricultural products. China actually overachieved the purchasing target on semiconductors and on products related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Nonetheless, China argues it is putting sincere effort into implementing the Phase One agreement. They emphasized that despite the global pandemic, they substantially increased imports of eligible goods from the U.S. during 2021 and took tangible steps in meeting targets ranging from improving intellectual property rights protection to opening up their financial sector. China called for the additional tariffs and sanctions that the U.S. imposed on Chinese imports to be lifted and emphasized that additional tariffs have proved futile in reducing the overall U.S. trade deficit, while adding to inflation pressure in the U.S.

Where Next for China-U.S. Trade Relations?

At the end of 2021, we asked our clients about the future of phase one of the U.S.-China trade agreement (Figure 4). The majority doubted there would be repercussions, with a roughly equal split between those expecting relations to get better (a new agreement) and worse (new tariffs).

Recent papers on U.S.-China trade relations, suggest that adverse effects of American-Sino tariffs are not only mutual but global and that Covid-19 made difficult U.S.-China trade relations worse (Funke and Wende, 2022; Zhu and Zheng, 2022). However, just because removal of tariffs would have economic benefits does not mean it will happen. The White House has maintained a relatively hawkish line on China; Trade Representative Kathrine Tai has said the administration would be looking to “all kinds of tools” available to them to combat the imbalance that China causes to international trade.

President Biden must contend with a number of factors in setting trade policy with China. First, tariffs on Chinese imports add to inflationary pressure in the U.S. Inflation has risen rapidly up the political agenda and removing or reducing tariffs could bring some respite. However, the impact of these tariffs on the consumer price index (CPI) is probably not as big as some believe it to be. About 65% of Chinese imports are facing tariffs from the U.S. side. However, according to calculations by Katheryn Russ (of the Petersen Institute of International Economics), if these tariffs were removed, the U.S. annual headline CPI inflation and PCE inflation (personal consumption expenditure, an alternative measure of inflation watched closely by the Fed) would be only 0.26 and 0.35 percentage points lower, respectively (using November 2021 values). Overall Chinese import content in American CPI is about 2% and in PCE slightly higher, 2.7%. Zhu and Zheng (2022) also found that the size of the U.S.-Sino trade in goods in terms of value is in fact overestimated by 8% on average, and the impact of American-Sino tariffs on the U.S. economy is somewhat smaller than it is often portrayed.

Still, with around $169.8 billion in trade, China is the United States’ third largest trade partner, and given that CPI and PCE indices include only certain goods and services, these measures might not fully account for the impact of these tariffs on the U.S. economy. Moreover, tariffs add to policy uncertainty for businesses when it comes to investment and hiring decisions, creating additional downward pressure on U.S. growth. Overall, the Phase One trade agreement is little short of being a failure, and Covid-19 has further reinforced the mood of nationalism by undermining confidence in the reliability of international supply chains.

‘It’s the Politics, Stupid’

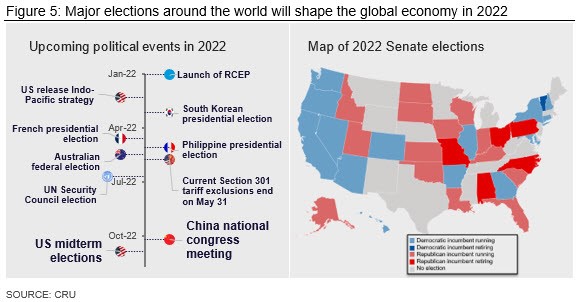

Ultimately, political concerns will be more important than economic ones in determining U.S. policy towards China. Most Democrats and Republicans are now in broad consensus that China represents the major threat to America’s status as the world’s economic, military and political superpower. This is in contrast to the situation under the Obama administration where many in Washington still argued for a cooperative approach to China. The focus of rivalry has moved away from tariffs towards competition in strategic technologies such as AI, and a drive by both China and the U.S. to build networks of allies (see below). However, appearing “soft” on China by removing tariffs will leave President Biden electorally vulnerable when his administration is publicly emphasizing a tough line. It would also risk expending political capital that could be better spent trying to resurrect the administration’s domestic agenda (e.g., the stalled Build Back Better bill). U.S. mid-term elections are in November (Figure 5), and based on current polling it will be very tough for the Democrats to retain control of both the House and Senate. At the same time, introducing new tariffs could contribute to the supply-chain and inflationary pressures that currently are hurting the U.S. economy, and which will be a major issue in the mid-terms. We think the most likely outcome is that there will be no movement in either direction on tariffs before the mid-term elections in the U.S.. Nevertheless, we might see pressures from U.S. businesses to push the Congress and USTR to extend or expand the China Section 301 tariff exclusion list, which will end in May (Figure 5). This would be a way for Biden to ease some pressures on U.S. supply chains without giving the public appearance of “going soft” on China.

Although maintaining the tariffs in place is far from ideal, this stability will suit the Chinese leadership. They have a number of domestic agendas – including inequality, decarbonization and reform of the digital sector – which a trade war would distract from. Their long-term aim is to move up the global value chain and to build multi-lateral economic relationships both upstream and downstream. This will diversify their economy away from reliance on U.S. consumers as a source of final demand, and loosen the control the U.S. has through its dominance of the global financial system.

There are risks to this static outlook. If the Russia-Ukraine situation escalates, and China sides with Russia (for instance, in seeking to circumvent sanctions), then relations could quickly deteriorate in ways that affect trade and investment. However, this is not our base case.

Going beyond 2022, U.S. trade policy towards China will depend on the outcome of the mid-term elections. Significant roll-back of the Trump-era tariffs is probably most likely in a scenario where the Democrats maintain control of both parts of Congress, but is not guaranteed even in that case. If – as currently seems likely – the Republicans take control of the House (and possibly the Senate), then cooperation between the White House and Congress on such a contentious issue will be unlikely.

U.S. and China Race to Win Allies in Indo-Pacific Region

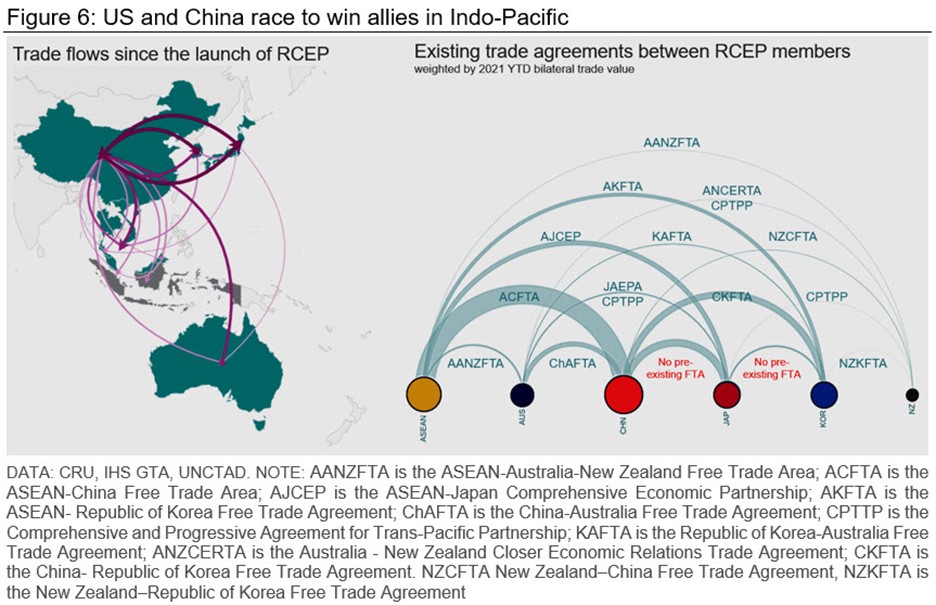

While we expect an “undeclared truce” between the U.S. and China in 2022, they are racing to win trade allies in the Indo-Pacific region to circumvent one another. Although countries in the Indo-Pacific region have been grappling with their engagements with the U.S. and China since 2017, they will potentially benefit from the rivalry between the G2 as both want to win their favor. On the one hand, China will aim to reinforce its partnership with countries within this region through RCEP and the Belt and Road Initiative. For example, we found Japan and South Korea are the beneficiaries of RCEP because there’s no pre-existing trade agreements (Figure 6). On the other hand, the U.S. has released its long-awaited Indo-Pacific strategy, attempting to strengthen allies within the region to counter China’s clout. Most recently, the U.S. and Japan have signed a trade deal to cut Trump-era tariffs on steel.

In conclusion, we don’t expect there will be any major movement in U.S.-China trade relations in either direction as both will pay more attention to their domestic agenda during this year. However, the results of these major political events in 2022 will shape the development of international relations in the upcoming years, including China’s entrance to CPTPP.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com