CRU

April 30, 2021

CRU: Inflation Pipeline Heats Up

Written by Jumana Saleheen

By CRU Chief Economist Jumana Saleheen and Principal Economist Alex Tuckett from CRU’s Global Economic Outlook

This month has seen strong signs that the speed of the recovery in the global industrial sector is feeding through to costs throughout the supply chain. Although this does present a risk to our forecast, our baseline case remains that these pressures are temporary and will not dislocate the global recovery. News on the activity side has been limited this month, and we have changed our GDP and IP forecasts only marginally. Our forecast for growth in world GDP in 2021 remains at 5.8%, while we have revised up growth in Industrial Production (IP) from 7.7% to 7.8%. We have further revised down our auto production forecasts for all major regions as the supply crisis in semi-conductors worsens and lengthens.

K-shaped Recovery Fuels Industrial Inflation

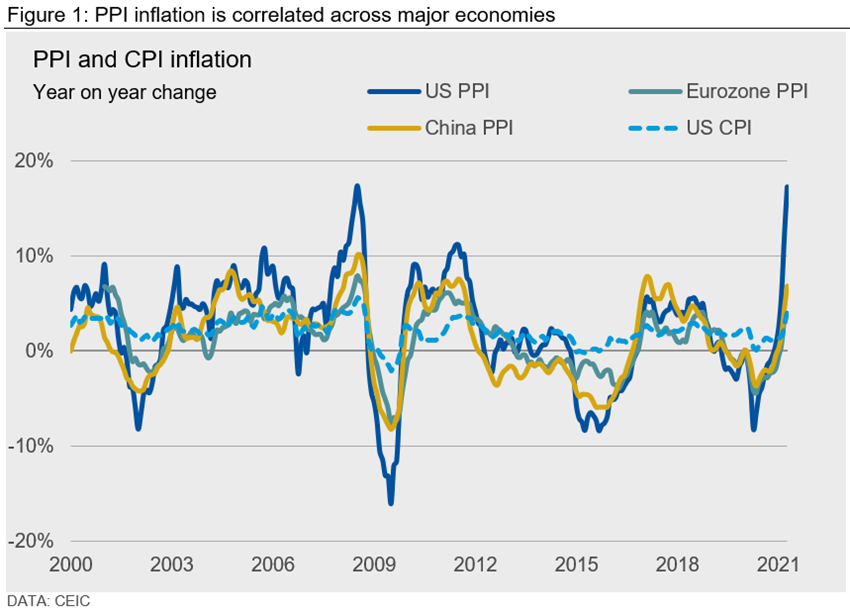

As set out in our last Global Economic Outlook, there has been an exceptionally strong recovery in global demand for durable goods, even as service sectors have remained hamstrung by social distancing restrictions in many economies. The strength of this industrial recovery had already propelled a rapid bounce-back in commodity prices. This “K-shaped” recovery – so-called because different sectors are recovering at different trajectories – is fueling cost pressures at multiple points in the supply chain. Producer price indices (PPIs) – which measure the wholesale price of goods as they leave factories – increased sharply in both the U.S. and China this month (Figure 1). PPI inflation is also rising in the Eurozone.

Such a rapid increase in PPI inflation has raised fears that we may be entering an episode of higher inflation in consumer price indices (CPIs), fueled by policy stimulus and rising private sector confidence. Such a scenario would also mean tighter monetary policy and equity markets have fallen in response.

The price pressures in the industrial supply chain are certainly real. However, we continue to believe that fears of a broader surge in inflation are premature, and that we are not heading back to the 1970s.

Inflation currently is being pushed higher because the recovery in global demand has been concentrated disproportionately in goods – particularly commodity-intensive durable goods. This relative shift in demand – together with the speed of the recovery in total demand – has put huge strain on global industrial supply chains. Costs have gone up throughout the value chain, from raw materials, to freight, to semi-finished and finished goods.

However, we do not expect the strength of durables demand to persist. Social distancing has prevented consumer spending on services, encouraging consumption on goods. With vaccination campaigns proceeding rapidly in advanced economies, we expect consumer demand to rotate towards services through this year. As this happens, cost pressures in industrial supply chains should ease.

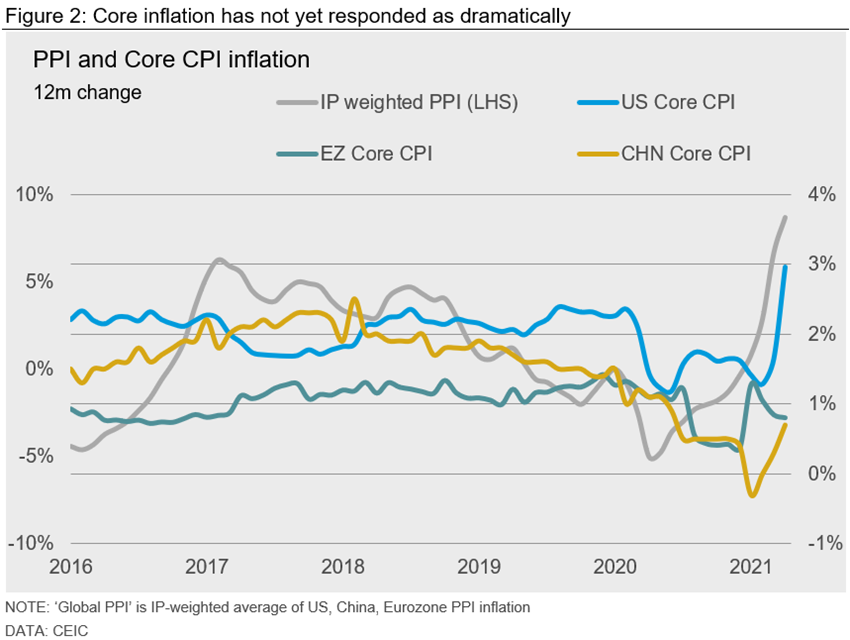

So far, signs of the global rise in PPI inflation feeding through to CPI inflation are mixed (Figure 2). The rate of U.S. headline CPI inflation rose sharply to 4.2% in April. The rate of core inflation (which excludes energy and food, components which are often volatile) increased to 3%, above the Fed’s target rate of around 2%. However, core inflation in China and the Eurozone remains below pre-pandemic rates. Even if core inflation is pushed up over the coming months, there is likely to be less concern than in the U.S.

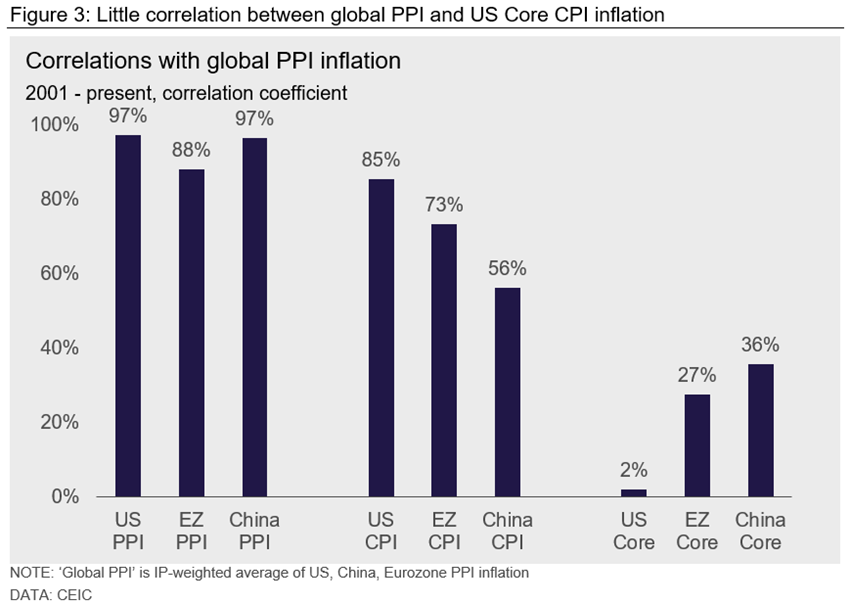

As Figure 3 shows, the link between PPI inflation and core inflation is not historically strong. PPI inflation is very highly correlated across countries, reflecting integrated global supply chains and the importance of globally-determined commodity prices. Headline CPI inflation in the major economies has significant correlation with global PPI. However, the magnitudes of moves are much smaller; a 1ppt rise in PPI is associated on average with only a 0.2-0.25ppt increase in headline CPI. Core U.S. CPI inflation has almost no correlation with PPI inflation, either domestic or global, and the correlations for China and the Eurozone are low.

The Federal Reserve is likely to emphasize similar points over the coming months—the increase in inflation is concentrated in the durable goods sector; it should prove temporary; and it does not mean that inflation is getting out of control. So far, the lack of a response in bond yields suggests that markets buy this message; U.S. 10-year sovereign yields have remained around 1.6%. But further inflation surprises will test this commitment.

Our baseline case continues to be that central banks will keep inflation under control. But inflation does pose risks to our forecast. Firstly, even if the strength of demand for durable goods proves temporary, the rise in inflation could feed through to inflation expectations and become more entrenched; the Michigan University survey showed household expectations for inflation over the next five years rising from 2.7% to 3.1%. Secondly, a super-strong U.S. recovery could push the labor market into overheating territory, resulting in broader and more sustained inflation. If either of these risks materialize, expect sharp movements in interest rates and currencies. That would have damaging effects for many firms and economies and could derail the global recovery.

Semi-conductor Problems Bite Deeper and Longer

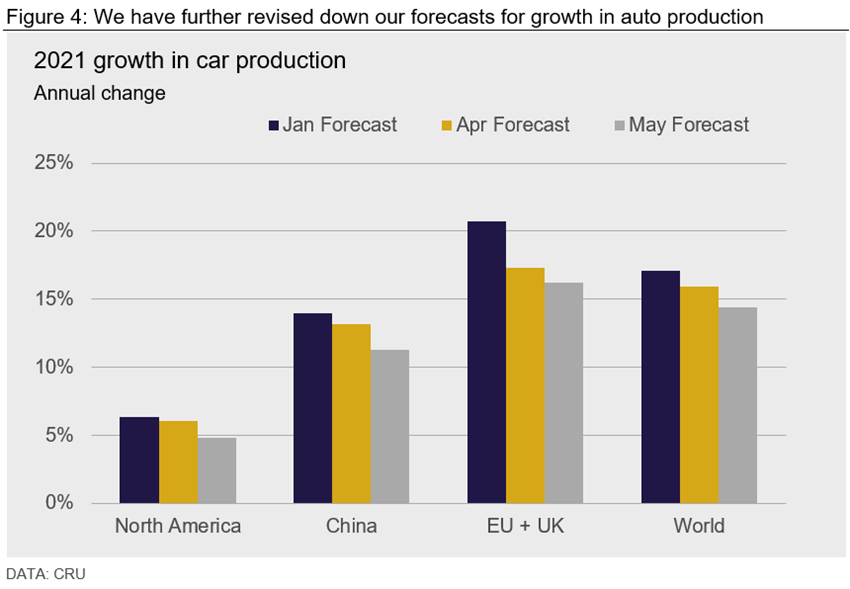

As well as pushing up inflation in the broad manufacturing sector, the strength of global demand for consumer durables has had a knock on effect on the automotive supply chain. As demand for consumer electronics and white goods has surged, automakers have found themselves pushed down the priority list and unable to procure the chips they need. This has resulted in reduced production in all major regions.

Initially, we had expected this to mainly be an issue in Q1, with Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) able to replace some of the lost production in H2. However, it has become increasingly apparent that the disruptions will be more serious and longer lasting. If anything, the strength of global demand for chips has meant the problem has spread to other industries – for example, the CEO of Intel has publicly stated that it may take two years for production to catch up with demand. A number of auto manufacturers have announced further closures of plants. EV production is likely to be at least partly insulated from these problems.

As a result, we have further downgraded our forecasts for auto production in all major regions (Figure 4). We now expect world production of cars to grow by 14.4% in 2021, down from 15.9% in our April forecast and 17.1% in our January forecast. We continue to expect the auto industry to make a strong recovery in 2021 H2 and 2022, as OEMs take advantage of strong demand for passenger cars. However, given this, there are risks that the semi-conductor crisis could continue even longer. Increasing chip capacity is slow and expensive; TSMC has announced a $2.8 billion investment in their Nanjing facility to increase production for the auto sector, but output will not come onstream until 2023.

The Recovery Continues, But Inflation Casts a Shadow

News on the activity side has been limited this month, and we have changed our GDP and IP forecasts only marginally. Our forecast for growth in world GDP in 2021 remains at 5.8%, while we have revised up growth in Industrial Production (IP) from 7.7% to 7.8%. This remains a strong recovery, with the caveat that the automotive sector is struggling with a shortage of semi-conductors. However, strong inflation data has highlighted that COVID-19 is not the only risk to the recovery.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com