CRU

March 16, 2021

CRU: Dollar Bears Pushed into Hibernation

Written by Ippolito Tarabini

By CRU Economist Ippolito Tarabini and Principal Economist Alex Tuckett, from CRU’s Exchange Rate Outlook Q1 2021

The latest foreign exchange market developments have shown the resilience of the dollar. Since the start of the year, the single most important driver of dollar strength has been U.S. fiscal policy, which has boosted expectations of U.S. growth and interest rates. However, while the stimulus is positive news for the dollar in the short run, the same is not necessarily true for the longer run. We thus maintain our view that the dollar will gently depreciate in the medium term, reflecting persistent twin deficits, modestly higher relative inflation and a more stable international environment.

2020: A Year in Three Phases

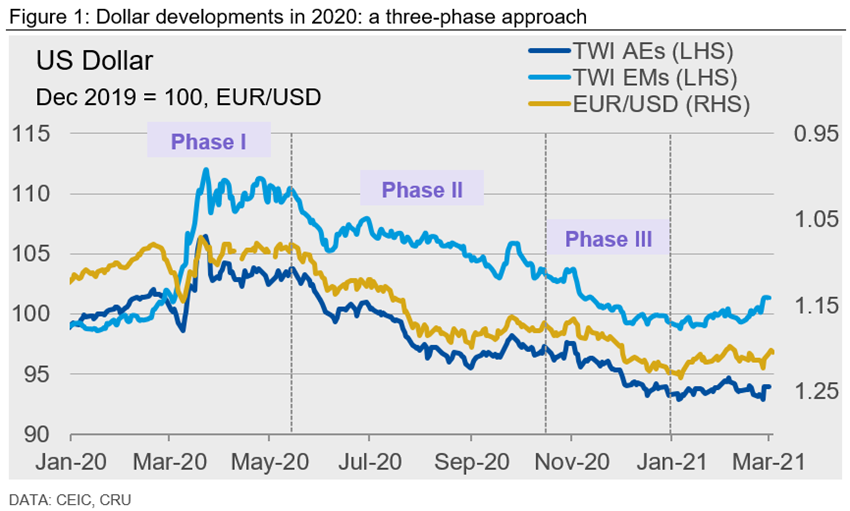

Phase I: In 2020, developments in foreign exchange markets have been driven primarily by the pandemic. The dollar reached its highest value against both Advanced Economies (AE) and Emerging Markets (EM)) in late March at the height of pandemic-related uncertainty. This led to a massive flight to safety, pushing up demand for dollars.

Phase II: After this initial strengthening, the dollar began losing ground against many AE currencies because of a more aggressive monetary policy easing by the Federal Reserve. U.S. interest rates had further to fall than rates in other AEs, and so the relative attractiveness of holding U.S. dollars over other AE denominated instruments was reduced. Fading virus-related uncertainty towards the end of Q2, when many countries began lifting their lockdowns, further depreciated the dollar.

Looking at the Trade Weighted Dollar (TWI) index, the euro has the biggest weight, meaning developments in the USD/EUR bilateral rate often drive overall movements of the index. For this reason, it is worth noting that the decision of EU leaders to issue common debt and use it to stimulate economic activity through Next Generation EU showed the bloc was more resilient—politically and economically—than previously thought. This resulted in diminished political risk and ultimately a stronger euro vis-à-vis the dollar.

Phase III: In the last quarter of 2020, the main driver of dollar weakness was the excellent efficacy results shown by a number of Covid-19 vaccines. This allowed risk-on sentiment to return and, unlike the previous phase of dollar weakness, benefitted EM more than AE currencies, as can be seen in Figure 1.

What Has Been Happening in 2021

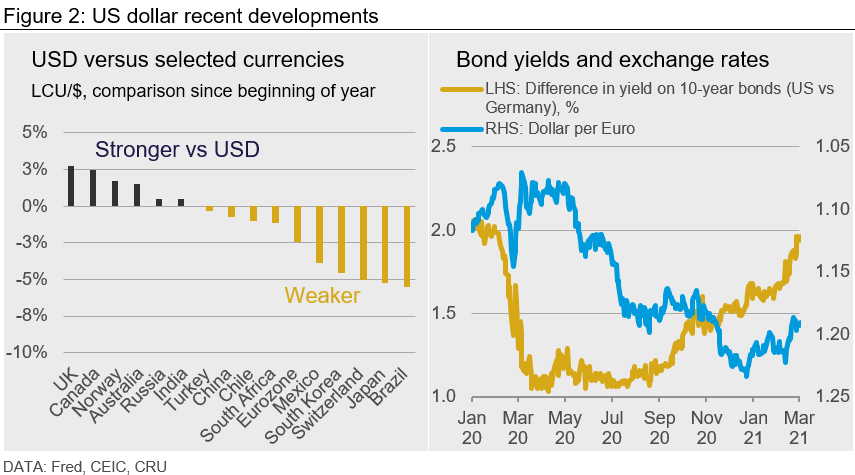

At the end of 2020, many market strategists were predicting the dollar would fall even further in 2021. So far, this has not happened. Since the start of 2021, the dollar has appreciated against many currencies, for various reasons. The Yen and the Swiss franc–low interest rate safe-haven currencies–have lost ground as global growth, driven by vaccine inoculation, is expected to pick up. This trend is unlikely to reverse. Brazil has been one of the biggest “losers” against the U.S. dollar this year and this can be attributed to deteriorating investment appetite towards the country. For the Brazilian real to benefit from a booming global economy (as one would expect), political risk needs to ease; recent developments suggest the opposite is happening.

The euro also depreciated against the dollar in the first months of 2021 and the key chart to understand why that happened is the spread between U.S. and German bond yields, which significantly increased since the start of 2021. The key driver of this has been diverging growth prospects and interest rates. The new fiscal stimulus package (of $1.9tn), together with faster vaccine roll-out, has led markets to expect the U.S. recovery in 2021 to considerably outpace the Eurozone’s. In turn, this has led to widening interest rate differentials in bond markets (Figure 2), as markets bring forward their expectations of tighter Fed policy.

The few currencies which gained against the dollar, for very different reasons, are the pound sterling and the Canadian dollar. The pound has benefitted from the agreement reached between the UK and the EU on a post-Brexit deal; although this has caused disruption and costs for many firms, it has removed downside risk. The impressive speed of the British vaccine roll-out has also boosted the sterling. For the Canadian dollar, the strength against the U.S. dollar has been driven by both rising energy prices and an improving macroeconomic backdrop, which is likely to result in earlier QE tapering by the Bank of Canada.

Three Reasons Why We Still See the Dollar Weakening in the Medium Term

While we never shared the view that the dollar would sharply depreciate in 2021, our view was that the dollar would experience a modest depreciation on a trade weighted basis–both in 2021 and in the years ahead. Although the extension of the recent dollar gains has prompted us to revise our view for 2021, we still expect growing twin deficits, higher inflation, and more predictable trade policies to be dollar negative over the medium term.

Twin Deficits: the United States’ Exorbitant Privilege

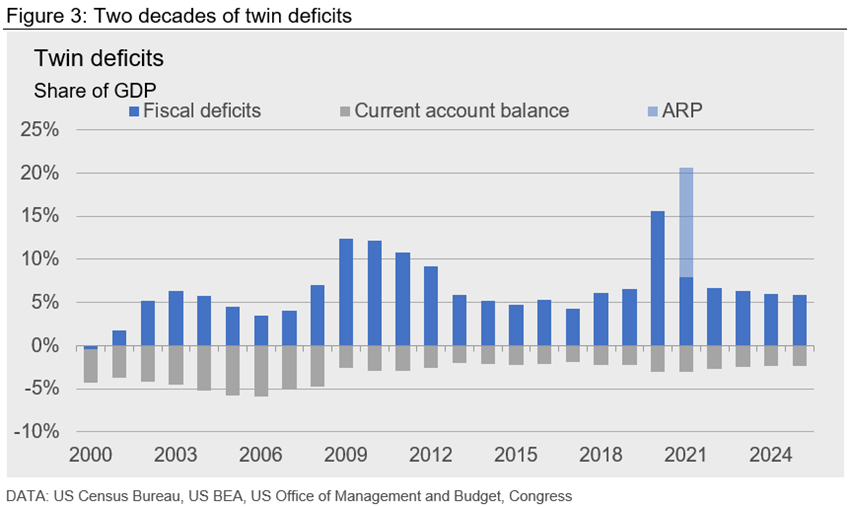

As Figure 3 shows, the U.S. has run a current account deficit every year since 2000–and that is not expected to change over the next five years. A current account deficit means a country spends more on its imports than it earns from its exports. To finance the deficit, it needs to borrow from abroad.

In the case of the U.S., these current account deficits have been accompanied by (and some would argue, partly caused by) persistent fiscal deficits (Figure 3). The fiscal deficit in 2020 and 2021 will be exceptionally high because of the stimulus packages enacted to counter the Covid-19 downturn. Such large fiscal deficits will not persist, but we do expect both deficits to continue over the next five years.

A current account deficit must be financed by capital inflow (or running down of overseas assets). The U.S. dollar has a unique status as the world’s reserve currency, and its dominant role in world commerce. This allows it to attract the capital inflows necessary to finance external deficits more easily than many other countries–a phenomenon termed “exorbitant privilege.” However, we believe that at some point continued external deficits are likely to weigh on the dollar’s value. A weaker dollar would, over time, act to narrow the current account.

Higher Expected Inflation

Expected inflation usually moves in the opposite direction of the trade-weighted dollar (Figure 4). Indeed, the 5-year, 5-year forward inflation expectation rate (5y5y), which measures the average expected inflation over the five-year period beginning five years from now, has increased steadily since its trough in late March 2020. This has been accompanied by a weakening dollar. Partly this correlation reflects a common cause. For example, in March 2020 fears that Covid-19 would cause a global recession led investors to expect lower inflation–and at the same time, flock to the safety of dollar assets. But it also reflects the long-term effect that higher inflation in the U.S. would have on competitiveness.

Over the past six months, two key developments have pointed to higher inflation in the U.S. Firstly, the Fed’s strategy review (announced in August 2020) resulted in a subtle but important revision: the Fed is now willing to temporarily tolerate above-target inflation after periods of below-target inflation. This is a contrast to the Eurozone, where the ECB’s target is to keep inflation below–“but close to”–2% at all times. Secondly, the Biden administration recently passed another generous fiscal stimulus, lifting both growth and inflation forecasts (Figure 4). These developments have increased the likelihood that the U.S. will experience moderately higher inflation–in particular relative to the Eurozone, which has struggled in recent years to bring inflation close to its 2% target. This supports our view of a gradually depreciating dollar in the medium term.

More Predictable Trade Policies

Throughout the Trump presidency, one of the factors supporting dollar strength was the abandonment of multilateralism by the White House. Unpredictable trade policies generated uncertainty, which ended up hurting outward-looking economies and their currencies more than inward-looking ones. We expect the Biden administration to pursue a very different approach, which will reduce uncertainty and therefore “safe haven” demand for the dollar.

Further Dollar Depreciation Delayed, Not Derailed

The sharp fall in the dollar seen in the second half of 2020 has not continued into early 2021. Expectations for a strong U.S. recovery this year–fueled by vaccination and fiscal stimulus–have pushed up the dollar. This has been reinforced by disappointment at the slow pace of vaccination in Europe. However, we maintain our view that in the longer term, the dollar will gently depreciate, with the USD/EUR pair and the TWI reaching respectively 1.25 and ~110 by 2025, reflecting inflation differentials, the twin deficits and a more predictable world.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com