Market Data

October 29, 2020

CRU: Three Key Issues from LME Week

Written by Jumana Saleheen

By CRU Chief Economist Jumana Saleheen and Principal Economist Alex Tuckett, from CRU’s Global Economic Outlook

In this Global Economic Outlook, we reflect on some of the most important risks to the forecast we discussed with clients during LME week. Three issues were foremost: risks to the recovery from the second Covid-19 wave, policy stimulus and recovery in China, and what the U.S. election could mean for the global economy. We continue to expect a “U-shaped” global recovery. We expect world GDP to contract by 4.3% in 2020, before growing by 5.5% in 2021, and world industrial production to contract by 4.7% before growing by 6.2%.

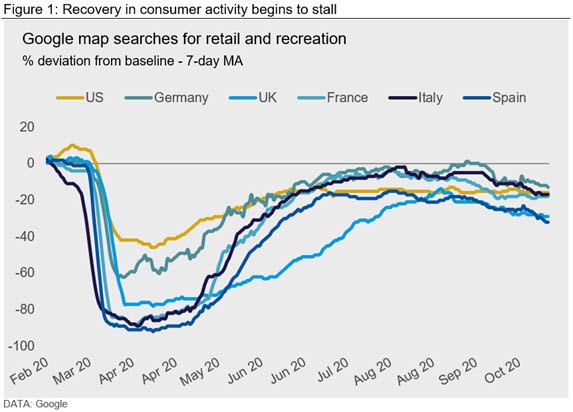

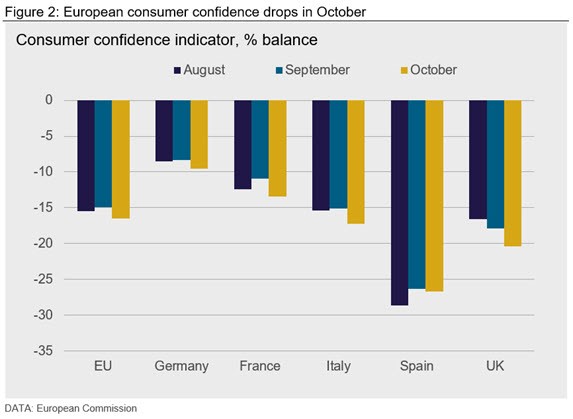

This slowdown in activity is already evident in some high frequency indicators. Figure 1 shows that after significant recovery over the summer, uses of Google Maps to locate retail and recreational establishments had begun to fall again in October. Figure 2 shows that consumer confidence in the largest European economies, after improving slightly in September, has dipped again in October. These trends have been evident even in Germany, which – until recently – had not seen the same increases in infection rates as France and Spain. This illustrates the importance of public perceptions. Even without statutory restrictions, if people are concerned for their health, then the economy will suffer.

Infection rates in the USA, which nationally never fell to the low levels seen in Europe during the summer, have also been surging in many states. Further surges in infection rates present a risk that economic momentum could deteriorate, particularly in the labor market.

Emerging market economies also remain vulnerable to Covid-19 infections, as the situation in India illustrates. Most emerging market countries have less policy space than advanced economies, making the response to the pandemic more difficult.

The second wave will have the greatest impact on consumer-facing services. Governments and businesses have invested heavily in adapting to the pandemic. Compared to the first wave, direct disruption to sectors such as construction should be minimal. However, the impact on service sectors will spill over to other sectors through supply chains. Furthermore, the fall in consumer confidence could have a broader impact, particularly on major purchases such as autos.

China—a Delicate Balance

So far, China’s recovery has been the envy of the world. Despite Q3 GDP data disappointing slightly, it is the only major economy forecast to grow for 2020 as a whole. There have been three main factors behind this:

• China has dealt with the health aspects of the crisis effectively, allowing both demand and supply sides of the economy to recover.

• Globally, this crisis has hit consumer-facing services the hardest, with industrial production relatively resilient, particularly sectors such as medical supplies and consumer electronics household goods where China has a dominant position in supply-chains.

• Policymakers have delivered rapid, large and effective stimulus, although this has been smaller than the U.S. package, and smaller than China’s own previous stimulus in response to the GFC.

Our view is that growth in 2021 will be determined largely by the government’s desire to catch up ground lost in 2020; China’s growth usually comes close to the target announced by the government. We continue to expect growth of 7.9% in 2021. This would leave growth over 2020 and 2021 averaging 5.2%. While the government has not announced official growth targets for 2020 or 2021, we believe this level of growth would be satisfactory to them, given that it is close enough to the growth target for 2019 of 6.0-6.5%. It would also be sufficient to bring unemployment down (a vital objective from a political and social point of view).

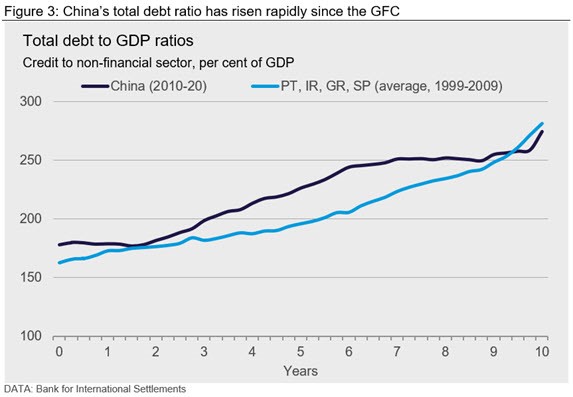

While we believe China’s policymakers will be able to achieve this growth, they face a delicate balancing act in doing so. Policymakers in China want to avoid repeating the post-GFC experience. Following the GFC, China’s stimulus was crucial in maintaining strong domestic growth and in helping the world recovery (in particular demand for commodities). However, that stimulus also resulted in a sharp increase in the total debt/GDP ratio (public plus private), from 139% in 2008 to nearly 260% by the end of 2019. In contrast, policymakers in Europe are keen to avoid making the opposite mistake; following the GFC, premature tightening of fiscal policy derailed the recovery in many countries.

While the central government debt ratio remains low, leverage has built up rapidly in local government and corporate sectors, and there is a lack of transparency. Such rapid increases in debt ratios have historically often been associated with financial crises and/or sharp slowdowns in growth. This is illustrated in Figure 3; since 2009, China’s total credit to GDP ratio has increased at a similar pace to that of Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain (the so-called ‘PIGS’ countries) in the 10 years from the inception of the euro to the GFC.

The Chinese government will be mindful of these risks, and will want to avoid a further build-up in credit unless absolutely necessary. If external demand is strong, further stimulus should prove unnecessary. However, if the global recovery falters—recent increases in infection rates have highlighted this risk—then China’s policymakers may be faced with the unpalatable choice of whether to allow higher unemployment in the short term, or allow a greater build of risks in the long term.

Looking further ahead, we continue to expect policy to pivot towards “dual circulation”—with the economy focusing more on domestic demand—and a shifting of domestic demand from investment to consumption. If successful, these agendas could make China’s economic growth more resilient and less reliant on bouts of credit-intensive stimulus; however, this will take some time.

U.S. Election—What Does it Mean for the U.S. Economy?

Nov. 3 sees U.S. voters go to the polls to decide the next president. Biden’s poll lead has remained steady, and with Americans voting early in record numbers, time may be running out for Trump to turn the tide. Statistical modelling based on state-level polls by website Five Thirty Eight puts Trump with a less than 15% chance of winning re-election. However, given the unusual circumstances of the election, nothing will be certain until Nov. 4—and if the result is close, possibly so for some time afterwards.

If he does win, what will a Biden presidency mean for the world economy? As set out in our client presentation, we see three main differences from a second Trump administration:

Trade: Biden will pursue a more multilateral approach to trade negotiations, and will be more predictable without being easier on China.

Green agenda: A Biden administration would heavily increase spending on energy transition and other environmental priorities, a positive for battery metals and copper demand, negative for oil demand.

Fiscal plans: Biden has ambitious plans to increase spending in several areas, partly financed by higher taxes on corporate profits and payroll and income taxes for higher income households.

The fiscal plans have the most important consequences for the near-term outlook for the U.S. economy. Figure 4 shows the scale of his announced spending plans, which are large relative even to the CARES stimulus of March, and the second stimulus package currently being proposed by Congressional Democrats (the HEROES Act in Figure 4 below). His planned increases in spending are only partially offset by tax increases (mainly on corporates and higher-income earners).

Biden’s spending will not be as rapidly disbursed as the emergency Covid-19 stimulus, as shown in Figure 5. However, taken together with a second emergency stimulus package, it could easily mean that the U.S. sees even greater fiscal stimulus in 2021 than in 2020. Biden’s spending may also have stronger multiplier effects on the economy. Fed research suggests that two-thirds of the CARES checks were saved or used to pay down debt, whereas spending on infrastructure, education and R&D should have stronger growth effects.

Risks to Our Forecast are Balanced

We remain confident in our view of a “U-shaped” global recovery; after a strong initial bounce-back, progress for most economies will feel more like a “long-slog.” As ever, there are both upside and downside risks to our forecast. On the downside, the rise in infection rates seen recently in many economies could derail the recovery. On the upside, next year may see considerable further fiscal stimulus in the U.S., depending on election results.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com