Prices

October 1, 2020

CRU: Reclassifying Chinese Scrap Imports is Unlikely to Solve Market Tightness

Written by Chris Asgill

By CRU Principal Analyst Chris Asgill, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

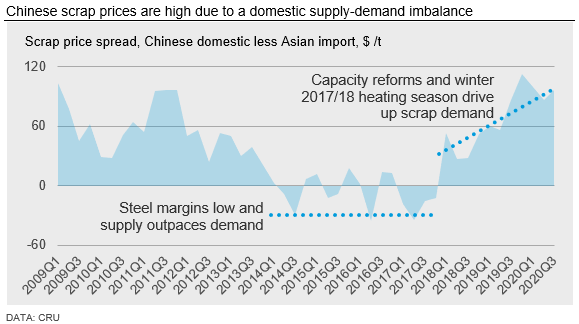

China has banned steel scrap imports for the past year as part of its solid waste management policies that affect imports on a wide range of metal scrap and plastic waste. Recently, policymakers announced that a review on these policies will be sped up with the aim to reclassify scrap metal as a resource rather than waste. The industry is keen on a change as the Chinese domestic steel scrap market is tight and prices are high. However, there are two reasons we do not believe policy alterations will change this situation.

First, scrap imports will remain small relative to domestic needs as anything greater would lift international prices and negate any economic benefit from importing. Second, using the reclassification of aluminum scrap as a proxy, little is likely to actually change because quotas will remain too small to loosen the market. Ultimately, accelerating the development of the domestic scrap supply chain is needed to rebalance the Chinese scrap market.

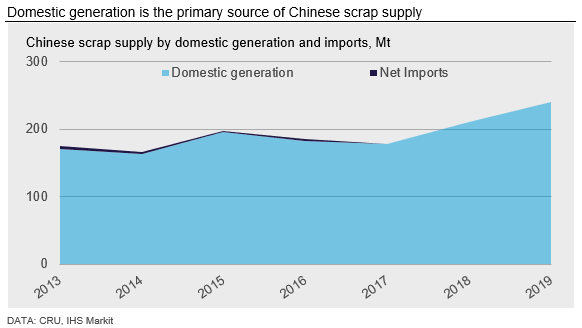

Chinese Scrap Import Volumes are Low Compared to Domestic Demand

China imported 2-3 Mt/y of steel scrap between 2014 and 2017 before restrictions were progressively implemented and a near outright ban was introduced in 2019. This volume is small in comparison to domestic consumption, which totaled 160-185 Mt/y over the 2014-2017 period and nearly 240 Mt in 2019 alone. Meanwhile, the Chinese steel scrap market tightened after a sharp rise in domestic demand following the first winter heating season called for hot metal output curbs at the end of 2017. This tightness was then exacerbated by the progressively tighter restrictions on scrap imports before bans were implemented in 2019.

Prior to these developments, Chinese steel scrap prices were in line with international markets. However, over the past 18 months, Chinese domestic prices have mostly exceeded a premium of $100 /t compared to other Asian import prices.

While an increase in scrap imports may somewhat alleviate upward pressure on domestic prices, the volume required to rebalance the market would lift international scrap prices quickly and eliminate any significant economic gain from imports. For example, had China imported just 5 percent of its scrap consumption in 2019, this would have amounted to imports of 12 Mt. This is the equivalent of two-thirds of the total scrap volume imported by Turkey—the world’s largest scrap importer—during the same year. In fact, this volume would have increased global scrap trade by nearly 20 percent. For completeness, we view 12 Mt as a reasonable volume of scrap imports to rebalance the Chinese market, as it is the equivalent volume required to displace the rise in steel billet imports in 2020, assuming the run rate of nearly 7 Mt YTD August continues to the end of the year.

Based on the Reclassification of Aluminum Scrap, Little is Likely to Change

Looking to aluminum as a proxy for potential adjustments in policy suggests that little will actually change in the market even if steel scrap is reclassified from waste to resource. Quotas for aluminum scrap imports have remained strict and imported volumes low despite a reclassification of aluminum scrap similar to what the steel scrap industry is targeting. Secondary aluminum producers have instead been importing secondary aluminum remelting ingots. For steel, this makes less economic sense due to the operating costs of the production processes involved because scrap needs to be processed into billet that is rolled rather than ingots that are remelted. Even so, a tight domestic scrap market is part of the reason Chinese billet import volumes have risen sharply, which in turn has supported both billet and steel scrap price gains in Asia.

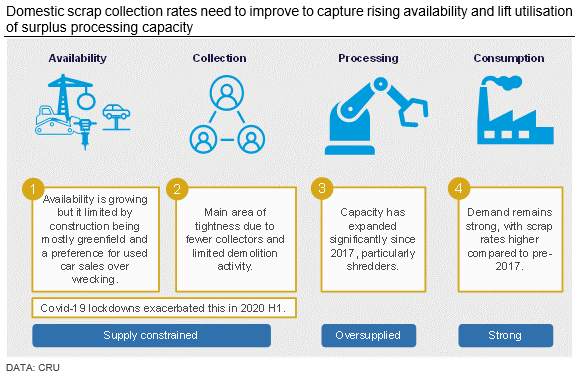

Increased Domestic Scrap Supply is Required to Balance the Chinese Scrap Market

For Chinese scrap prices to realign with international markets, the domestic demand-supply imbalance must be resolved. This is primarily resolved by improving collection rates. These have been limited by a preference for greenfield construction at the perimeter of cities and for used car sales as opposed to wrecking end-of-life vehicles. This has been compounded by fewer collectors being available to source and deliver material to scrap yards.

Greenfield construction means there are no old structures at the site to demolish, meaning there is limited scrap generated from the building activity. Conversely, brownfield development would first require the demolition of existing structures. The reinforcing bar, beams, and other steel products that make up the structure of the building are then recycled as obsolete scrap and used in steel production. Were brownfield development to occur more frequently, there would be more scrap on the Chinese market.

A similar situation is occurring for motor vehicles. While policies have been introduced in recent years to increase the attractiveness of auto wrecking, used cars are still preferred by consumers. In prior years, the sale of car components from wrecked vehicles was prohibited, which limited the profitability of auto wrecking. Policies introduced in more recent years now allow these sales.

Still, even if brownfield construction and auto wrecking issues were resolved, another key constraint on supply is the number of scrap collectors. Scrap collection in China has been a challenge for market participants, and recent policy changes are only now helping incentivize this activity. Scrap market participation has also been hampered by the need for yards to occasionally relocate due to planning changes that accommodate increasing urbanization.

In conclusion, we do not expect ongoing policy revisions to steel scrap imports to meaningfully rebalance the Chinese scrap market. Without improving domestic supply chains, scrap will remain a high cost for Chinese mills regardless of changes to import restrictions. This is because increasing import levels even by a relatively small amount would result in substantially higher international scrap prices.

CRU will continue to monitor regulations as they are published in China. In the meantime, if you would like to discuss this further, please do get in contact with us.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com