Prices

September 29, 2019

CRU: Chinese Scrap Supply Surge Will be Utilized

Written by Tim Triplett

Editor’s note: The Chinese government currently bars exports of ferrous scrap to other parts of the world to assure China of an adequate domestic supply. As this analysis by CRU Principal Analyst Chris Asgill points out, China’s economy will eventually generate a scrap supply that far exceeds its scrap consumption, opening up the doors to scrap exports in the late 2020s. The following article was originally published in July 2018, but its conclusions are unchanged.

Chinese obsolete scrap availability will expand rapidly in the coming years and will gather further pace in the next decade and beyond. However, even with availability rising, scrap could theoretically remain unutilized if investment in collection and processing is not incentivized. This incentive ultimately comes from having a scrap price high enough that market participants are profitable and yield a return on any capital invested. On the other side of the coin, scrap prices must be low enough to stimulate domestic consumption or enable profitable exports. The price of scrap is strongly correlated with the cost of hot metal and, applying CRU’s long-term forecasts for iron ore and coking coal, we expect scrap prices will remain sufficiently high to incentivize investment in scrap collection and processing, while remaining low enough to stimulate increased consumption in steelmaking. Even so, supply growth will exceed the ability of the Chinese steel industry to consume scrap and exports will be required, which will support EAF output growth elsewhere in the world.

Scrap Availability to Rise Sharply

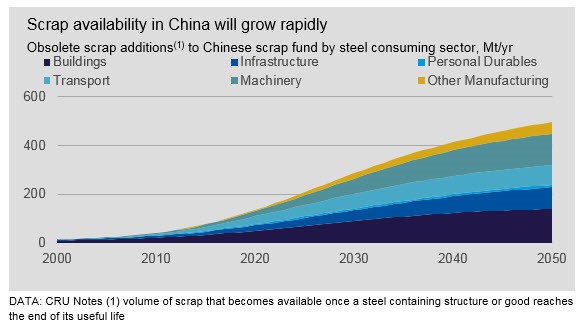

We have shown in prior publications that Chinese scrap supply will grow rapidly. In the medium-term, this is driven by the acceleration in steel consumption in buildings and infrastructure during the 1980s and 1990s. In the longer-term, this growth gathers significant momentum as the buildings and steel-containing goods from the boom period of the 2000s reach the end of their useful life. This means that steel containing items (i.e. buildings, goods, etc.) reaching the end of their useful life will increase scrap availability (i.e. additions to the scrap fund) by over 300 Mt/y from the 2030s and over 500 Mt/y by the 2050s (see chart).

Scrap Supply Will be Economical to Recover

While scrap availability is growing, there remain the questions of whether China will have sufficient capacity and incentive to collect, process and consume or export this scrap. We expect that increased scrap availability in China will lead to greater arisings, as it will be more economical to recover and consume or export the scrap compared to disposal in landfill. Landfill costs are already high in China and we expect that, as incomes rise and consumption in the country lifts, disposal of household consumer waste will increase pressure on landfill costs. Beyond this, we estimate the incentive price for investment in the collection and processing of scrap sits well below the price steelmakers will need to lift scrap consumption.

Processing Capacity Already Expanding

Historically, the scrap industry in China has predominantly served the needs of induction furnace-based steelmakers (IF’s). In recent years, China has completely eradicated this section of the steel industry. Meanwhile, the government is pursuing its objectives of improving air quality and the environment overall. In this vein, China is encouraging increased scrap use and has been making moves to improve the legitimacy of the industry. Presently, China has 200 companies that are “qualified” to process scrap, meaning these companies are officially recognized and get a 30 percent VAT rebate. Furthermore, regulations on the sale of used car parts have been eased, meaning there is a greater potential for profit from the dismantling of end-of-life vehicles, selling old parts and recycling the metals contained in the vehicles.

During 2017, profitability in the Chinese steel sector rose sharply as demand was above expectations. Coupled with structural capacity closures (n.b. both IF and other steelmaking routes), this lifted steel prices above cost increases throughout the period. With capacity constrained and high margins on offer, mills in the country were willing to find any means to lift output. This led to a sharp increase in scrap rates (i.e. consumption per tonne of steel output). As evidenced by increases in scrap prices during the period, scrap rates at both BOF and EAF facilities rose above those attributable to the transfer of steel production and scrap consumption from IFs. With scrap supply rising rapidly and domestic demand up, there has been significant investment in scrap processing equipment (i.e. shredders, shears, balers, etc.) to support the increase in consumption.

An example of the scale of the expansions that has occurred is that a major equipment supplier, with 40 percent market share, had shredder orders for $50 million in 2016, but these rose to $200 million in 2017. Using estimated investment costs per tonne of shredder capacity (n.b. see section below, “Capital and Collection Costs are Sufficiently Low”), the investment in 2017 implies a capacity expansion of 25 Mt during the year for this company alone and of 63 Mt for China as a whole, given its market share. It is likely the simple calculation for China as a whole overstates the increase in capacity, though we estimate Chinese scrap arisings rose by 29 Mt y/y in 2017, which indicates a sizable portion of this capacity was likely installed (n.b. not all would have been operational for the full year, nor operating at full utilization immediately). For 2018, the company has orders for five shredders per month, implying 9 Mt of shredder capacity for the company and 20 Mt for China as a whole. Our discussions with some of those involved indicate that the scrap market is now considered as a high-growth market and there are attempts by many players to “get in early.” One possible outcome of this is that the country could see excess scrap processing capacity in the medium-term.

Scrap Prices are Linked to Ironmaking Costs

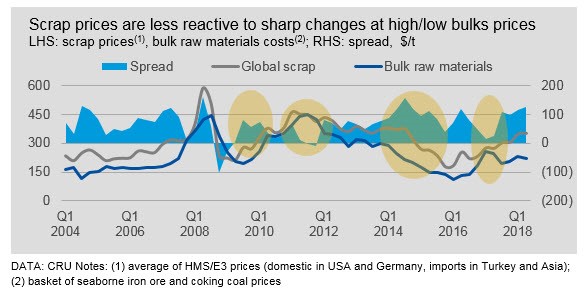

Over the medium-term, scrap prices are intrinsically linked to ironmaking costs. BOF-based steelmakers make decisions about scrap rates based on a range of factors, but one key consideration is the price of scrap relative to the cost of an additional tonne of hot metal from their BFs (i.e. the marginal cost of hot metal production). When scrap prices are high relative to ironmaking costs, scrap rates are reduced and vice versa.

That said, while scrap supply is highly elastic, a floor price exists where scrap inflows to yards slow and supply is reduced. This means that, at lower ironmaking costs, scrap prices can remain relatively higher. At the upper end of ironmaking costs, scrap prices are capped to a degree. Effectively, once scrap prices reach a certain level there is no barrier to further supply, as the price covers the cost of recovering any material that becomes available. CRU’s long-term prices for iron ore and coal imply that hot metal costs will be within the normal range (i.e. not be at the top- or bottom-end of the range), therefore, scrap prices will correlate closely with marginal hot metal costs.

Capital and Collection Costs are Sufficiently Low

The cost of investing in and operating a scrap supply chain is sufficiently low to sustain supply. The typical size of a shedder is 2,000 horsepower and processes about 150 kt/y of scrap. The investment cost for this equipment is about RMB8 M plus another RMB18 M for ancillary equipment, which equates to a unit capital cost of ~$25 /annual tonne, equivalent to a capital charge of only ~$2 /t scrap processed. Meanwhile, we estimate that a scale price (i.e. that paid by processors for inflows of scrap) of $160 /t is required to cover labor and other costs of collection. Coupled with processing costs, at an estimated $30-35 /t, and including the capital charge, this implies a minimum price of less than $200 /t is required to incentivize scrap supply.

CRU’s current long-term forecasts for iron ore and coking coal imply a steady-state scrap price of ~$250 /t and, in our view, this is sufficiently high to incentivize expanding scrap supply and processing.

From Consuming the World’s Ores to Supplying Scrap Metal to the World

Even though it will be economic to collect, process and consume the significant increase in Chinese scrap supply, steel demand growth has slowed and we expect demand will start to contract by the late-2020s. This means that scrap availability is rising at a time when the Chinese economy is less able to consume it.

Chinese steelmakers currently use low scrap rates by world standards and, in the next five to ten years, scrap rates will increase in both steelmaking processes (i.e. BOF and EAF). We expect this because scrap prices will be competitive with ironmaking costs, while still being at a level to incentivize supply.

Beyond the mid-2020s, we expect that steel supply will see greater growth in EAF-based steelmaking capacity, particularly as the capacity swap program accelerates and stimulated by the closure of BFs as they reach the point of reline. In addition, we expect that the reline schedules of many BFs may need to be brought forward as the ongoing production controls to reduce pollution lead to damage, as BFs are stopped and restarted. In other words, across the Chinese BF population, there will plenty of decision points each year when a switch to EAF production could be made, which should make the overall transition towards greater EAF production manageable. That said, the EAF-based share of steel output will be limited by the sheer scale of regional Chinese steel markets that are ultimately better served by BOF-based steel operations.

This limit on EAF-based output and the upper limits to scrap consumption in steelmaking mean that, ultimately, domestic scrap consumption cannot be enough and a surplus of scrap will arise. Because of this, we expect that China will definitely need to start exporting scrap from the mid-2020s, though at a low level of about 10 Mt/y. The pressure to export will increase rapidly in the decade that follows, with scrap exports lifting to as high as 20-40 Mt/y by the mid-2030s. With strong EAF output growth elsewhere in the world, these exports will be needed.

Conclusion: Available Scrap Will be Utilized

Scrap availability in China will expand rapidly over the coming decades and we expect there will be sufficient incentive for investment in collection and processing supply chains. In other words, the price required by steelmakers to increase and sustain higher scrap rates is high enough to incentivize supply.

Increased scrap consumption during a period of reduced growth or a contraction in steel demand and production means that hot metal production in China will fall. We believe that hot metal output has peak (n.b. in 2014) and declines in output will accelerate from the late-2020s. This view is built into our forecasts for iron ore and coking coal prices, which are key drivers of ironmaking costs.

Scrap prices are linked to ironmaking costs and based on our long-term forecasts for iron ore and coking coal we estimate a steady-state scrap price of ~$250 /t, well above the minimum price of ~$200 /t that we expect is required to sustain investment in scrap collection and processing.

While scrap consumption in China will grow, this will not be sufficient to offset the significant growth in supply. Ultimately, this means that exports will be required, but not until the late 2020s.