Market Segment

September 12, 2019

CRU: U.S. Minimill Costs Drop Below Integrated Mill Costs…But for How Long?

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Analyst Ryan Smith

Operating costs for flat-rolled minimill producers have dropped in 2019 as weaker steel markets have pulled down metallics prices. This has meant that operating costs for minimills are now in line with integrated producers in the USA. However, the current cost level is not expected to be maintained. (See related article, “Minimills Have a Big Cost Advantage, Right? Not So Fast…”, elsewhere in this issue.)

U.S. Minimills are Typically Higher Cost

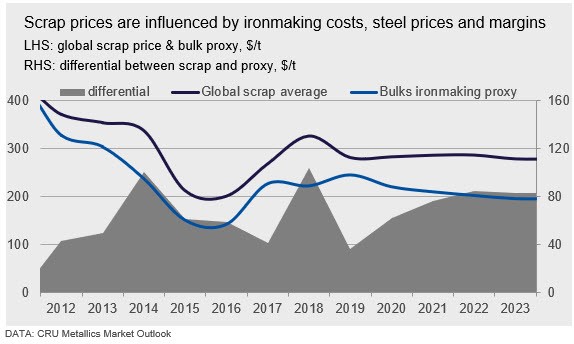

On an operating cost basis, U.S. integrated mills are typically lower cost than their minimill peers. Scrap prices are tied to the marginal cost of hot metal production—meaning that the input for scrap-based steelmaking is typically higher than the average ironmaking bulks mix (n.b. iron ore, coal and coke). Supply and demand dynamics in both steel and scrap markets influence scrap prices, and high steelmaking margins will increase the spread between scrap prices and ironmaking costs and vice versa. In the USA, domestic scrap prices are influenced by export scrap prices—with U.S. export scrap prices being linked to European and Turkish scrap prices. Scrap prices in Europe and Turkey are in turn driven by the marginal cost of hot metal production in these regions, which is typically higher than in the USA.

Minimill Costs are More Volatile

Lower-cost U.S. integrated producers, such as U.S. Steel and ArcelorMittal USA, have access to captive iron ore pellet that is charged to the mill on a cost plus logistics basis. These same integrated producers also have varying access to captive coal and coke that is also charged to the mill on a cost plus logistics basis. Higher-cost integrated producers, such as AK Steel, typically buy all or most of their iron ore and coal from merchant producers such as Cleveland-Cliffs and SunCoke. In this case, the raw material purchases are typically conducted on a multi-year contract basis, with quarterly price adjustments that take into account changes to seaborne raw material prices, shape premia, steel prices and CPI movements.

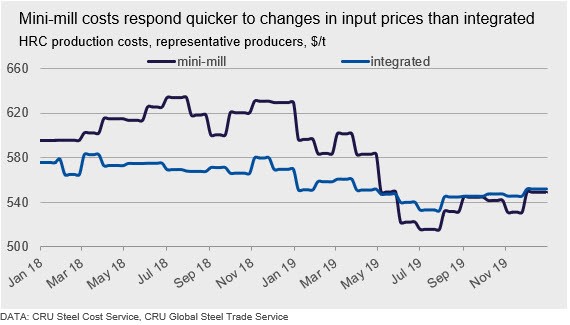

These pricing arrangements for the integrated producers have an important impact on costs—the costs for integrated producers tend to move slowly, changing with contract adjustments and/or mining cost changes. As such, the costs for integrated steelmakers are less volatile than for minimills.

Metallics prices have moved downwards in 2019 and costs for minimill producers have declined quickly. The costs for minimill producers are much more responsive to changes in market prices due to the shorter timeframes on which minimills purchase their raw material inputs—typically on a monthly basis. As can be seen in the chart below, the costs of a minimill are more volatile when compared to that of an integrated producer.

What’s Happening in 2019?

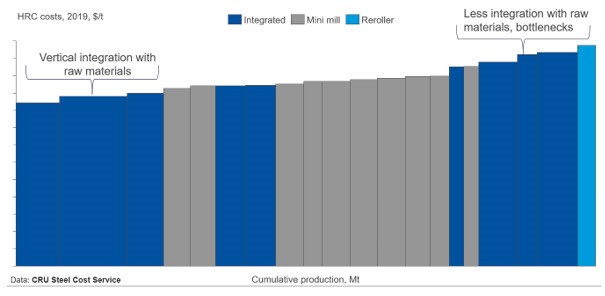

In 2019, steel markets have weakened and scrap prices have dropped closer to marginal hot metal production costs. In the USA, this has meant that flat-rolled production costs for minimill producers have dropped, with minimills on average now lower cost than the higher-cost integrated operations. In addition, raw material prices for iron ore and coal have been high for most of 2019 due to supply side issues, although these issues have been unwinding in recent weeks. The result of these swings in raw material prices has led to partitioning on CRU’s HRC cost curve, which can be seen in the chart below.

Will Minimills Stay Lower Cost?

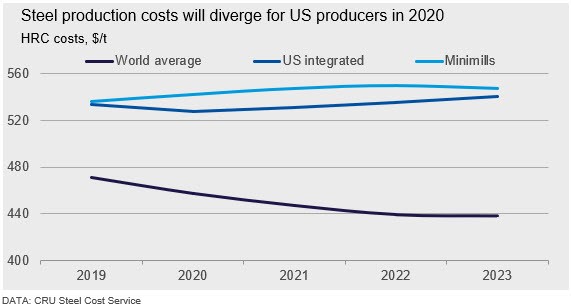

CRU does not expect that the current cost level for minimills will be maintained—low scrap prices reduce U.S. domestic scrap supply, and there is a growing appetite for scrap from the growing minimill sector. In addition, CRU forecasts that steel prices and margins will increase from 2019 Q4 and these factors signal that scrap, and metallics prices more generally, will rise. In turn, this will lift minimill costs back above average integrated mill costs in 2020 and they will stay higher than integrated mill costs out to 2023.

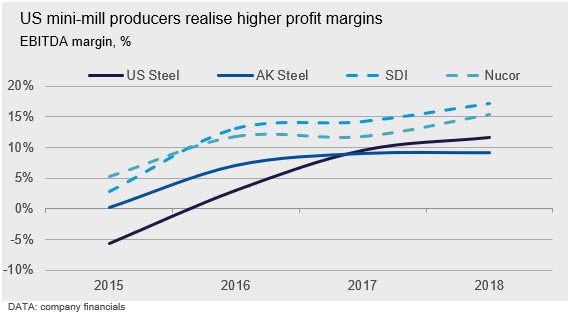

This relative improvement in cost position will come as welcome relief for the integrated sector in the USA, which struggles to realize the EBITDA margins and profitability of the minimill sector. From 2020 onwards, the integrated sector will again see cost inflation, which is explained in more detail below.

What Does CRU’s Steel Cost Model Tell Us About the Drivers of the Cost Changes for the Integrated Sector?

CRU’s Steel Cost Model provides superior granularity and transparency that allows the user to understand exactly what is driving changes in costs and competitiveness in the USA and the rest of the world.

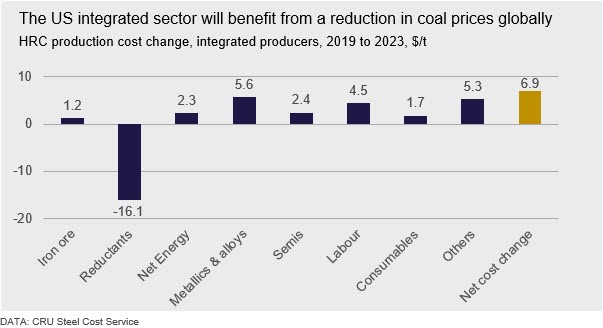

Overall, costs will rise for the integrated sector from 2020 onwards for a variety of reasons, including:

• Iron ore supplied on a contract basis will feel upwards price pressure due to rising HRC prices and U.S. inflation.

• Iron ore supplied on a cost plus logistics basis will see delivered prices rise due to mining cost inflation.

• Rising metallics prices will also impact U.S. integrated producers, but to a lesser extent than minimills.

• Higher wage rates, negotiated by workers unions in 2018 when steel prices were high, will increase labor costs.

A forecast decline in coal prices globally will somewhat offset these cost rises. However, overall, costs are forecast to rise.

Conclusion

The operating costs of integrated mills are generally lower than minimills. However, in 2019, weaker steel markets have pulled down metallics prices and, with them, the costs of minimill producers. Given our expectations for the raw materials and metallics markets, CRU does not believe the current low cost base of minimill producers will be maintained—minimill costs will rise as the steel market improves and additional minimill capacity begins to come online. The integrated sector will see some relief as their costs drop below those of the minimills in 2020, but from 2020 onwards costs for the integrated sector will also begin rising.