Prices

September 8, 2019

CRU: Understanding U.S. Iron Ore Production

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Senior Analyst Erik Hedborg

Part one of our three-part series: What’s next for U.S. iron ore production?

The U.S. is blessed with a wealth of natural resources, including oil, gas, gold, copper, timber and coal. In addition, the country has large iron ore deposits that have supported its steel industry for more than a century. Today, the U.S. is the world’s fourth largest steel producing country, but what stands out is its high share of EAF production. In 2019, CRU estimates that 68 percent of the country’s carbon crude steel output will be produced in the EAF route, compared with 27 percent for the world as a whole. The country’s integrated steel production, which makes up the remaining 32 percent of total output, is heavily reliant on domestic iron ore supplies. U.S. iron ore producers sell almost all their volumes to steelmakers around the Great Lakes, including Canadian steel mills, thereby making the country a marginal exporter of iron ore to the seaborne market.

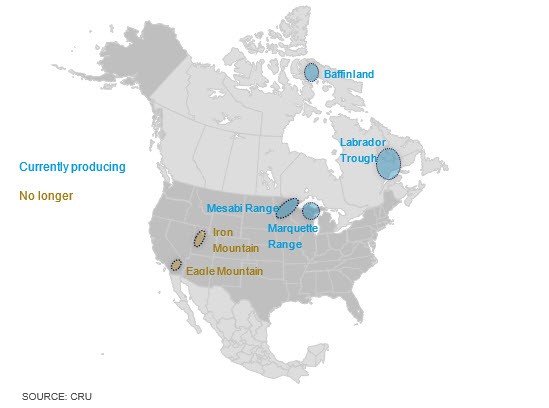

Supply Concentrated Around the Great Lakes

Most U.S. iron ore production takes place in the Mesabi Range, located west of Lake Superior in northeastern Minnesota. At present, there are six operational mines producing ~40 Mt/y from this deposit, which stretches 180 km from Grand Rapids to Babbitt. Another important region with large reserves is the Marquette Range, located in northwestern Michigan. However, production in the Marquette Range is only ~8 Mt/y as Cliffs’ Tilden mine is currently the only asset in operation.

Like almost all iron ore in the world, U.S. iron ore comes from a sedimentary rock type called a Banded Iron Formation (BIF). BIFs are comprised of interbedded layers of silica and the iron-bearing minerals hematite and magnetite.

The iron ore deposits found in the U.S. have not been subjected to the same geological processes of weathering and enrichment that created large “direct shipping ore” resources in Australia, northern Brazil, South Africa and India. As a result, the U.S. deposits are characteristically low in iron content, hard, fine grained and high in silica, giving rise to a rock type known as taconite. This ore type requires extensive grinding to separate the iron from the silica and other impurities. The fine particle size of the resulting iron ore concentrate is better suited to pelletizing than sintering, which is why almost all U.S. iron ore is pelletized. In fact, the physical properties of the local taconite deposits actually led Cleveland Cliffs to pioneer the iron ore pelletizing process in the 1950s. The low grade of taconite and requirement for grinding and pelletizing raises mining Site Costs, but the high-grade pellets that are produced are a very efficient and productive feed for the blast furnace (BF). Therefore, they attract a high premium in the market.

Who Produces Iron Ore in the U.S.?

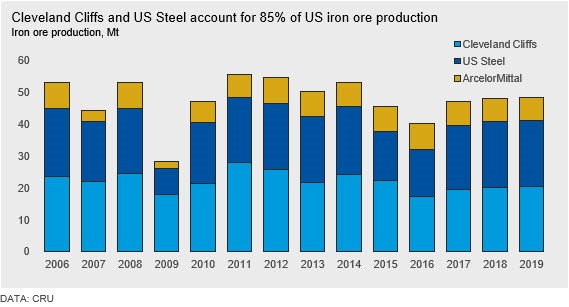

The country’s iron ore production is dominated by three companies centered around the Great Lakes. All three companies primarily produce pellets, which is why BFs in the U.S. have the highest pellet rates in the world.

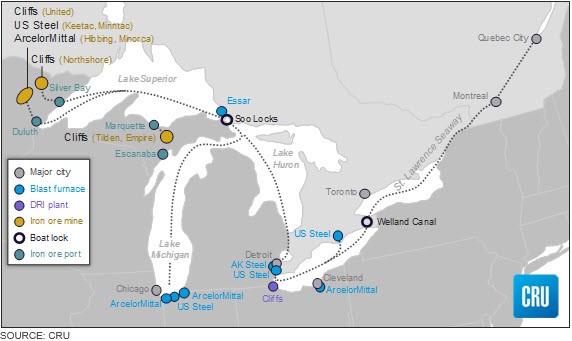

Cleveland Cliffs is the largest producer. The company operates the Northshore and United mines in the Mesabi Range that produce ~9 Mt/y of BF pellets. Most iron ore mines in the Mesabi Range are centered around the town of Hibbing, including the United mine. However, Northshore is 70 km away at the northeastern end of the geological formation. Iron concentrate from Cliffs’ Northshore mine is railed 75 km to a 5.5 Mt/y pelletizing plant at the port in Silver Bay on Lake Superior. The pelletizing plant completed a $90 million upgrade in August 2019, which now allows the plant to produce up to 3.5 Mt/y of low-silica DR pellets. The remaining 2 Mt/y capacity is still dedicated to BF pellet production, making it the only facility in the country able to produce both DR and BF pellets. Around 2.7-2.8 Mt/y of the new DR pellets will be shipped to Cliffs’ new $830 million DRI plant currently under construction in Toledo, Ohio. From the middle of 2020, the plant will produce 1.9 Mt/y of HBI for use in EAFs.

Cliffs also owns the only operational mine in the Marquette Range, Tilden, which produces 8 Mt/y of BF pellets that are railed 26 km north to Marquette on the south shore of Lake Superior. Product from Tilden is sold to Essar’s steelworks at Sault Ste. Marie in Canada and to AK Steel’s Dearborn works in Detroit. The adjacent 5.5 Mt/y Empire mine, also owned by Cliffs, was idled indefinitely in August 2016.

U.S. Steel produces marginally less iron ore than Cliffs, owning two mines in the Mesabi Range to supply the company’s integrated steel production. The Keetac and Minntac mines currently produce a cumulative ~19 Mt/y of BF pellets, which get shipped from Duluth to U.S. Steel’s BFs in the U.S. and Canada. The 2015 idling of production at Granite City resulted in lower pellet demand, which influenced the decision to reduce iron ore production by idling the smaller Keetac mine. However, in 2017, as iron ore prices recovered from the 2015–2016 slump and global pellet premia kept rising after the Samarco accident, U.S. Steel decided to increase its pellet production by restarting operations at the Keetac mine in order to enter the seaborne market. In recent years, U.S. Steel has exported ~2 Mt/y of pellets to Japan, and the 2018 decision to resume operations at Granite City has helped keep Keetac fully operational ever since.

In 2019, U.S. Steel announced the idling of two BFs near Detroit and Chicago. This has cast doubts over the future of its own iron ore production, a topic we will discuss further in part two of this series.

The third company, ArcelorMittal, operates the Minorca mine that ships all 2.8 Mt/y production of fluxed pellets from Duluth to Indiana Harbor on Lake Michigan. In the Mesabi Range, there is also the 8.5 Mt/y capacity Hibbing mine, which is owned by ArcelorMittal (62.3 percent), Cliffs (23.0 percent) and U.S. Steel (14.7 percent). Ore from the Hibbing mine is processed and pelletized on-site before being railed to Duluth for shipping across the Lakes, with each company taking a pro-rata share of production. In August 2019, ArcelorMittal took over responsibility as mine operator from Cliffs.

Why are U.S. Iron Ore Exports So Low?

The geography of the Great Lakes basin allows easy and cheap access to North American steelmakers. However, exporting to the seaborne market is not as easy. All iron ore that is shipped on Lake Superior is loaded through the ports of Duluth, Silver Bay or Marquette. The lake connects to Lake Huron via the Soo Locks that are closed from January to March every year as the water freezes. Usually, iron ore is stockpiled during this time to ship as soon as the weather permits. However, at times of exceptional iron ore prices, companies in the past have railed ore from the Mesabi and Marquette Ranges, 550 km and 110 km respectively, to the port of Escanaba on Lake Michigan. There are no locks between Lakes Michigan, Huron and Erie. Ports on these lakes are accessible all year round, with the help of icebreakers, allowing ship transport to all the major BFs in the region.

Transport to mills around the Great Lakes is carried out by freighters that were built on the Great Lakes and are too large to traverse the Welland Canal. The Soo Locks are larger than the locks at the Welland Canal, which permits vessels up to 60,000 DWT, so-called “Lakers,” to serve the Great Lakes.

The size of vessels that can reach the Atlantic Ocean from Lake Erie is limited by the length of the locks on the St. Lawrence Seaway, which runs 600 km from the top of the Welland Canal to Montreal. The largest bulk carriers that can navigate this seaway are called Seaway Maxes, which have a capacity of up to 40,000 DWT. They are also known colloquially as “Salties” as they can travel on the sea. In order to export iron ore, “Salties” must transport iron ore through the Great Lakes and down the St. Lawrence Seaway to Quebec City, a total journey of approximately 2,000 km. Quebec City is the furthest inland a Panamax vessel can travel. At this location, iron ore from “Salties” is transferred to the larger Panamax vessels for seaborne exports. In total, CRU estimates that the entire process from Great Lakes loading to completion of Panamax loading has a cost of ~$20 /t. From here, the Panamax vessels are competing in a seaborne iron ore market dominated by larger, more efficient Capesize vessels. These logistics hurdles explain why the U.S. is not a major iron ore exporter.

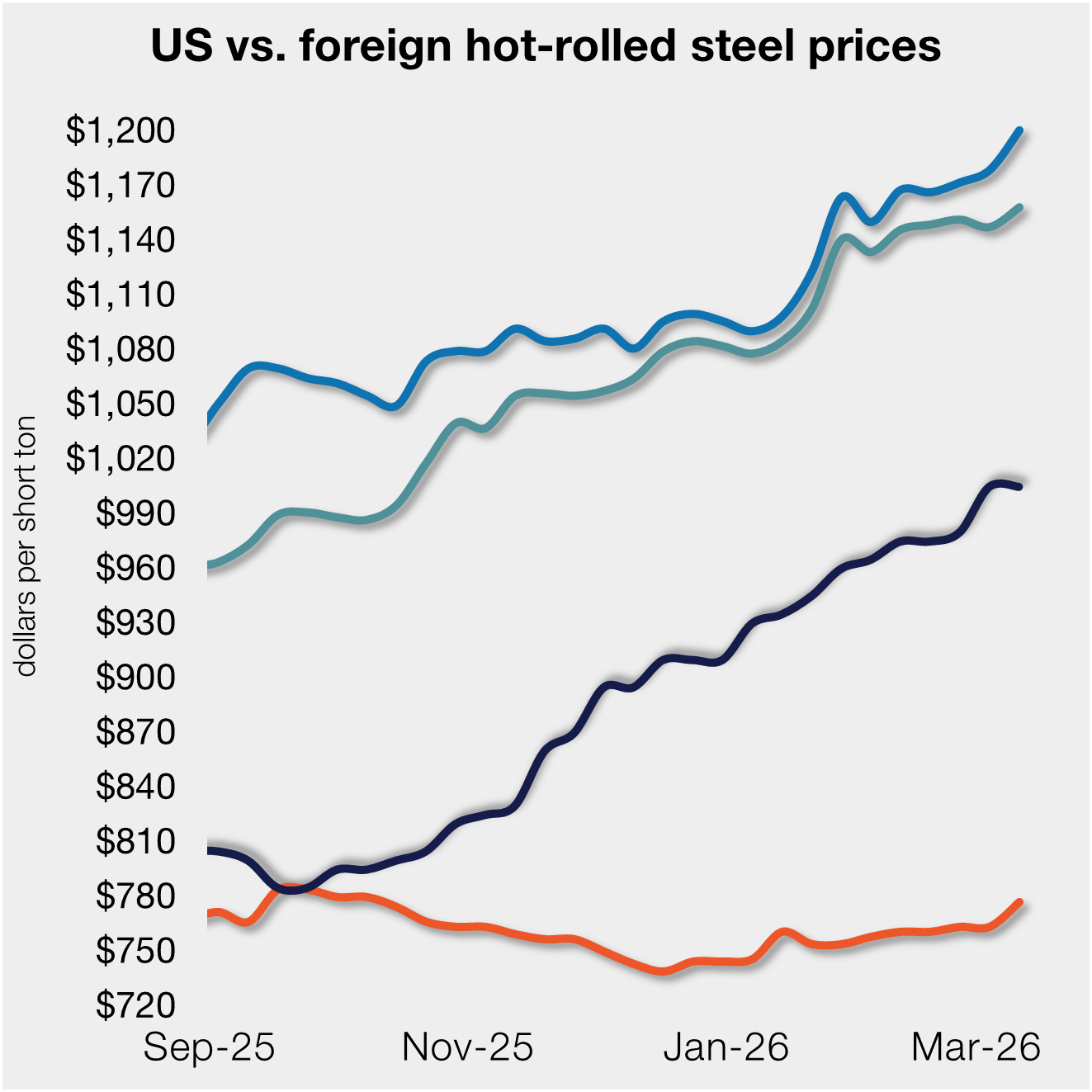

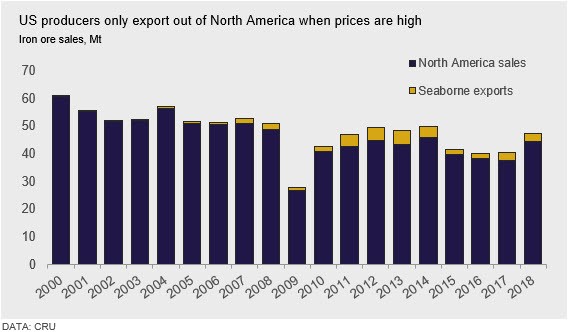

That being said, iron ore exports do increase when market conditions are favorable, such as when seaborne pellet prices are elevated and domestic steel prices are depressed. Exports were significantly higher during the iron ore price boom between 2011 and 2014 and, more recently, the high pellet premia caused by the Samarco and Vale dam accidents.

America First… at Least for U.S. Iron Ore Producers

There is a mutual dependence and, consequently, a capacity linkage between steelmakers around the Great Lakes and U.S. iron ore producers. The cost of getting iron ore in and out of the Great Lakes is simply too high for any major trade to take place with the rest of the world. Therefore, the U.S. remains a very marginal player in the seaborne iron ore market. In 2019, seaborne iron ore exports are expected to be ~3 Mt, which accounts for ~0.2 percent of global seaborne trade. Due to its high share of pellet production, the country is slightly more important in the seaborne pellet market with a ~3 percent market share.

U.S. hot metal production has declined steadily over the last 20 years, from 54 Mt in 2000 to 28 Mt in 2019. This has resulted in domestic iron ore production falling steadily as the seaborne market has simply not been consistently profitable. The high production costs and logistical challenges of getting product onto the seaborne market make it very difficult for U.S. Steel, Cliffs and ArcelorMittal to compete with low-cost producers in countries such as Australia and Brazil. Therefore, the prospects for the country’s iron ore producers are closely tied to U.S. hot metal demand.

Unfortunately, in 2019, falling steelmaking margins have resulted in further BF closures around the Great Lakes. This will have an immediate impact on U.S. iron ore producers—a topic we will explore further in part two of this series.

Editor’s note: Other analysis by Daniel Keogh and Adam Smith.