Prices

September 3, 2019

CRU: Growth Risks Further Skewed to the Downside

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Principal Economist Lisa Morrison

The last month has been interesting from a forecast standpoint given the reversal in the Fed’s monetary policy stance at the end of July, new developments in the U.S.-China trade war and a shift in currency policy in China. Through all this policy change, we continue to see a two-speed global economy where manufacturing is declining while services are holding their own, or at the very least are not losing momentum at the same rate as manufacturing. As one would expect, the continuing policy turmoil has not improved the global economy’s growth prospects as we look towards 2020.

Recent News Not Reassuring for Global Growth

Since we last published our Global and Economic Outlook, a flurry of events upended the idea that August would be calm from a policy standpoint. The following developments increase the already high level of uncertainty in the economic environment that decisionmakers currently face as 2019 draws to a close:

July 31: The Fed lowered interest rates by 25 bp, reversing its 25 bp rate increase in December. The Fed cited weak inflation, trade policy and the threat of weaker global conditions as key reasons for the cut. Chairman Powell also noted that the Fed wanted to extend the gains made in the longest-ever U.S. economic expansion. In theory, this should have inspired confidence in Americans (that their economy would continue growing) as well as anyone exporting to the U.S. (who is not warring with the Trump administration over those exports). Financial markets did not think that the Fed went far enough, so the U.S. dollar strengthened following the announcement.

Aug. 1: President Trump tweeted that, as of Sept. 1, the rest of China’s exports to the U.S. would be subject to a 10 percent tariff, with the promise of an increase to 25 percent if trade negotiations, slated to resume in September, did not make progress. Thus, this decision would place all Chinese exports to the U.S. under a tariff. Some have posited that the president felt emboldened to act because the Fed decided to be more supportive of the U.S. economy (and he is hoping for interest rates to move even lower), but it is also possible that he simply wanted to shake things up ahead of the upcoming trade negotiations with Beijing. The president later backtracked on this announcement, postponing tariffs on around $155 billion in goods (40 percent of the remaining China exports to the U.S. not already under tariff) until Dec. 15.

Aug. 5: China’s state-owned entities were instructed to cease buying U.S. agricultural products. In addition, the Chinese RMB depreciated beyond the 7.0/$ mark, an unexpected turn, particularly since Beijing has been trying to maintain the RMB at that psychological level in order to stabilize currency outflows. In a surprise twist, by the end of the day, the U.S. declared China as a “currency manipulator.” Though the designation is largely symbolic, it will force Beijing to defend itself in another arena and has dealt another blow to the already deteriorating trade negotiation environment.

Aug. 23: China announced it would levy a 10 percent tariff on $75 billion in U.S. imports starting on Sept. 1. President Trump responded by raising the existing 25 percent tariff on Chinese imports to 30 percent and threating to order all U.S. companies to find alternatives to China.

Risk-Off Sentiment Returns

In addition to the policy actions noted above, the data news during the last month has not been very positive. Recent releases from the U.S., China and Europe provide more evidence that the momentum in these three large economies is slowing. Perhaps the most discouraging result came from Germany, where GDP declined in Q2, underscoring just how hard its export-oriented manufacturing sector has been hit by the trade war.

Beyond the disappointing data news, there are many outstanding trade issues that weigh on the outlook. The Oct. 31 deadline for Brexit is approaching quickly and although our base case continues to expect a deal will be struck between Britain and the EU, the likelihood of “no deal” increases as each day passes without a resolution. Japan and South Korea are feuding and the trilateral USMCA agreement is not yet in force.

It is not surprising that equity markets have lost value and volatility has been increasing (see chart below). There is a renewed risk-off sentiment, which has led investors to pile into “safe” assets such as long-term government bonds and the U.S. dollar. Thus, long-term bond yields have fallen and, in the U.S., the spread between the 10-year and 2-year bonds went negative in intraday trading. This is significant because, in the past, this particular inversion of the yield curve, on a consistent basis, has signaled recession within 13 to 24 months of occurring.

Central banks have certainly fueled this risk-off sentiment. The minutes of the Fed’s July 30-31 meetings indicated a rather wide range of opinion, from proposals for a 50bp rate cut to votes against a rate cut entirely. The minutes of the ECB’s meeting on July 25 indicate a clear preference on the part of the participants for monetary accommodation for “an extended period of time.” In addition, recent commentary indicates that the ECB could make a very big move at its Sept. 12 meeting, which could include further interest rate cuts and another round of quantitative easing (QE). We also expect the People’s Bank of China to implement slightly more easing to offset any further negative fallout from the trade war with the U.S. and we note that restrictions on credit growth have already been loosened.

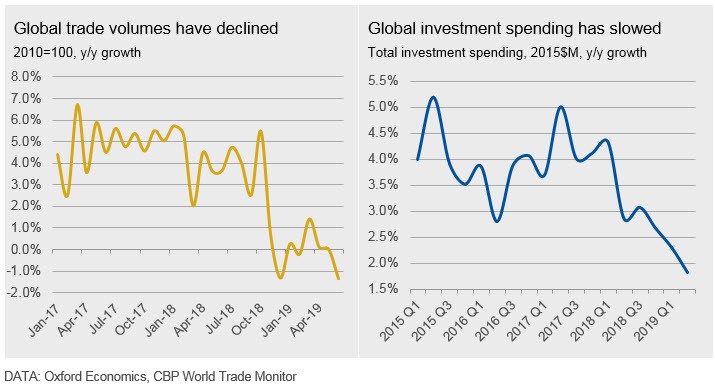

Although financial markets are not necessarily a good predictor of GDP growth, they reflect the views of economic actors and affect our forecast view via the confidence channel. The ongoing volatility in the markets erodes optimism in the economy’s future prospects. When businesses become less confident in their future prospects, they cease to hire and they delay capital outlays. If the lack of hiring then leads to a reduction in employment, consumers spend less. With both consumers and businesses reducing their demand for goods and services, in an environment where the trade war has cut off the potential to increase exports, the rate of economic growth is highly likely to fall. We can see in the charts below just how much investment spending and global trade volumes have slowed since the trade war escalated in mid-2018.

Manufacturing Weakness and Heightened Uncertainty Reduce the Global Economy’s Growth Prospects

The events that transpired over the last month have made us less optimistic about the prospects for the global economy. We have lowered our forecast for global GDP growth to 2.6 percent in 2019, down from 2.7 percent in July.

Although the Fed’s intent with its rate cut was to inspire confidence in the continuation of the U.S. expansion, that effect has largely been undone by the escalation in the U.S.-China trade war. Moreover, none of these policy announcements change the fact that the two-speed global economy we discussed in last month’s Global and Economic Outlook remains in place. Currently, the global manufacturing sector continues to decelerate while non-manufacturing/services is not experiencing the same level of decline. The reason for this disparity lies in the fact that the two largest end-use industries for metals—construction and transportation—are both experiencing slowdowns.

We do not believe there will be any infrastructure-related stimulus enacted on a scale that could be implemented in time to boost the construction sector in 2020. However, there has been speculation that Germany could enact a fiscal stimulus package to boost their faltering economy and in turn the Eurozone region.

Next year, the vehicle sector could recover once emissions standards are settled in China, India and Europe, allowing for some upswing in manufacturing. This rebound would be undermined, of course, if the U.S. slapped tariffs on imports of cars and parts from the large exporters. Our previous work has shown that Japan, South Korea, Germany and Italy would have the most to lose under U.S. auto tariffs.

We continue to expect the U.S.-China trade war to rumble along without a resolution. The issues of subsidies, intellectual property rights and market access are complex and will not be easily settled. Furthermore, the negotiating environment continues to be poisoned by the tit-for-tat tariff escalations. Both sides in the conflict are now entrenched in their positions and we cannot yet see how that logjam will be broken.