Government/Policy

June 4, 2019

Shock But No Awe: Trump Thumps Mexico with 5 Percent Tariff

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Principal Economist Lisa Morrison

During the last two years, we have become somewhat accustomed to waking up to some fresh, new policy idea of the Trump administration, disseminated via presidential tweet. However, the levying of tariffs on Mexican imports, as punishment for Mexico allowing Central American migrants to traverse their country in order to knock on the door of the U.S., really has us scratching our heads.

President Trump announced May 30 that, beginning on June 10 (i.e. 11 days later), the U.S. would slap 5 percent tariffs on all Mexican imports. Furthermore, the tariff rate would rise an additional 5 percent per month until Mexico did something about the crisis at the U.S. border.

The details as to how this came about are not entirely clear, but it surely seems that the U.S. president is trying to get the attention of the new Mexican administration, headed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO).

The relationship between tariffs and immigration is not something encountered in economic theory classes, so we cannot draw on any academic training to explain this. Even the politics are a bit fuzzy because this is exactly the sort of thing that would keep a populist like AMLO from ratifying the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement (USMCA), which President Trump claims to support. We wonder, instead, whether this is a way for the U.S. president to appear tough on immigration and to finally kill any chance of a North American free trade agreement, both of which were key campaign pledges of candidate Trump.

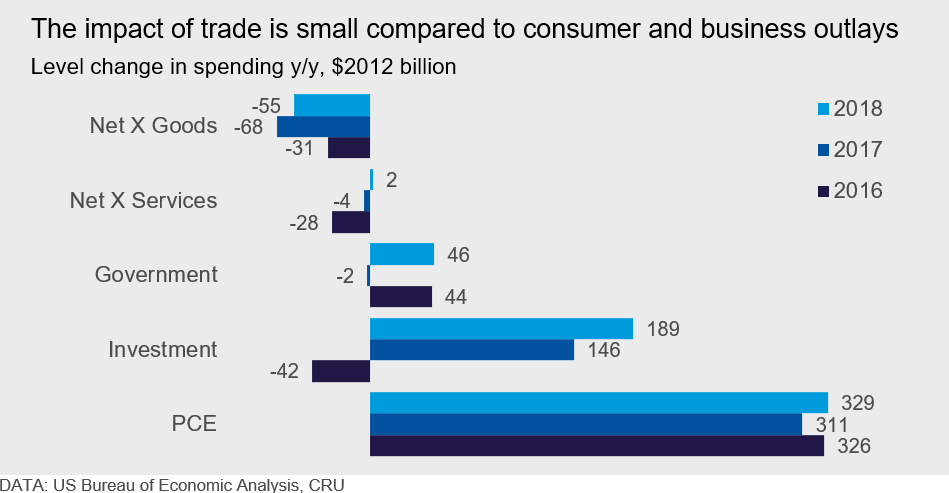

As we have noted in previous commentary, the impact of trade on the U.S. economy is relatively small, at the aggregate level. The chart below shows the y/y change in the level of spending, in real terms, by each major category of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As we can see, the net loss to GDP from trade was $55 billion in 2018. This was only a little more, in absolute terms, than the contribution to GDP of government spending ($46 billion) last year.

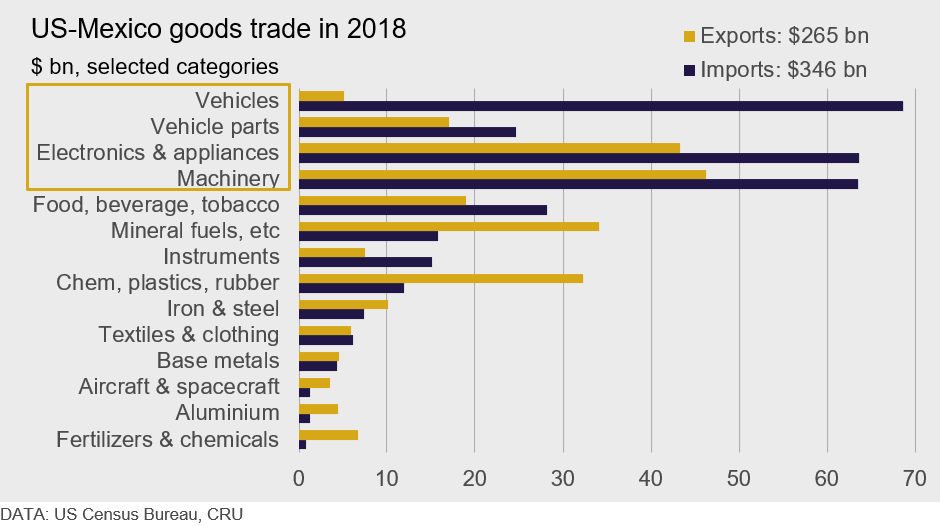

Autos, Electronics, Appliances and Machinery Will Bear the Burden of the Tariffs

The losers from these tariffs are highly concentrated in a few sectors, as illustrated in the chart below.

At $346 billion, Mexico provided 13.6 percent of the total value of U.S. imports in 2018; this was second only to China at nearly $540 billion. Vehicles and parts together accounted for ~27 percent of Mexican exports to the U.S. in 2018. Add in electronics, appliances and machinery, and these four sectors together account for nearly 64 percent of U.S. imports from Mexico. Conversely, these four categories, along with food, mineral fuels and chemical products, constitute roughly 65 percent of U.S. exports to Mexico.

During Q1 2019, the U.S. imported, on average, $28.9 billion per month from Mexico. By our calculations, a 5 percent tariff on one month of Mexican imports amounts to $1.4 billion. However, if the president is not satisfied with Mexico’s progress on the border issue, the tariffs will increase by 5 percent per month, reaching a maximum, permanent tariff of 25 percent by Oct. 1, 2019. Thus, by October, assuming the average import value of $28.9 billion, U.S. importers would be paying $7.2 billion for goods sourced from Mexico. This assumes, of course, that demand for goods from Mexico does not decline as a result of the tariffs, or that there isn’t a rush to buy from Mexico in the next few months before the tariff rate becomes prohibitive.

The White House has released a statement at www.whitehouse.gov laying out the policy.