Market Data

February 14, 2014

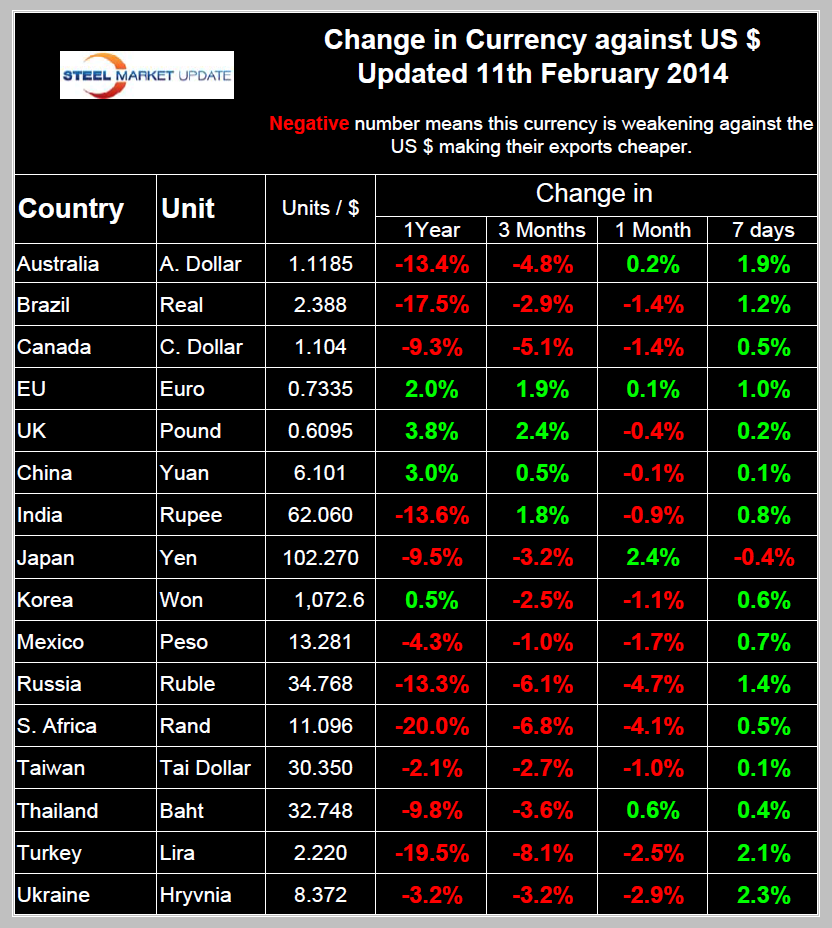

Currency Update for Steel Trading Nations

Written by Peter Wright

In the month since this analysis was last published, the US dollar has strengthened against 12 of the 16 nations that we consider to be major players in either the iron ore market or in steel product trade or both. Most notably, the Russian Rouble and the South African Rand have declined by 4.7 percent and 4.1 percent, respectively. The Turkish Lira has declined by a further 2.5 percent. The currencies of Brazil, Canada and Mexico are each down in the region of 1.5 percent. In this one month analysis, the notable exception is the Japanese Yen which has recovered by 2.4 percent. In the last 7 days these trends have reversed with 15 of the 16 currencies under examination here, strengthening against the US $. Most notably the Turkish Lira and the Australian Dollar have bounced back by 2.1 percent and 1.9 percent (Table 1).

This is a period of great turmoil in the currency markets, particularly in those of the developing world as capital flees towards safe havens and governments attempt to use monetary controls, (interest rates) to prop up their currencies.

At SMU we have come across two very good articles in the last couple of weeks that help to explain what is going on. There are included below.

The first is from Bloomberg on January 24th:

“The worst selloff in emerging-market currencies in five years is beginning to reveal the extent of the fallout from the Federal Reserve’s tapering of monetary stimulus, compounded by political and financial instability. The Turkish lira plunged to a record and South Africa’s rand fell yesterday to a level weaker than 11 per dollar for the first time since 2008. Argentine policy makers devalued the peso by reducing support in the foreign-exchange market, allowing the currency to drop the most in 12 years to an unprecedented low. Investors are losing confidence in some of the biggest developing nations, extending the currency-market rout triggered last year when the Fed first signaled it would scale back stimulus. While Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa were the engines of global growth following the financial crisis in 2008, emerging markets now pose a threat to world financial stability. “The current environment is potentially very toxic for emerging markets,” Eamon Aghdasi, a strategist at Societe Generale SA in New York, said in a phone interview yesterday. “You have two very troubling things: uncertainty about the Fed policy, combined with concerns about growth, particularly in China. It’s difficult to justify that it’s time to go out and buy emerging markets at the moment.”

Developing-nation currencies sold off after a report from HSBC Holdings Plc and Markit Economics indicated yesterday that China’s manufacturing may contract for the first time in six months, adding to concern that growth is losing momentum. The declines were part of a broader slide in global markets today, with European stocks falling, U.S. stock futures lower and Asian shares tumbling. Yields on 10-year German bunds slipped to an 11-week low, while the yen, considered by investors as a haven, rose versus all 16 major counterparts tracked by Bloomberg. Currencies of commodity-exporting countries that depend on Chinese demand sank, with the rand plunging 0.9 percent, following yesterday’s 1.1 percent decline. Brazil’s real fell 0.4 percent while Chile’s peso climbed 0.2 percent after decreasing 1.2 percent yesterday.”

The second is a translation from Der Spiegel published on February 10th.

Troubled Times: Developing Economies Hit a BRICS Wall

It was 12 years ago that Jim O’Neill had his innovative idea. An investment banker with Goldman Sachs, he had become convinced following the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks that the United States and Europe were facing economic decline. He believed that developing countries such as China, India, Brazil and Russia could profit immensely from globalization and become the new locomotives of the global economy. O’Neill wanted to advise his clients to invest their money in the promising new players. But he needed a catchy name. It proved to be a simple task. He simply took the first letter of each country in the quartet and came up with BRIC, an acronym which sounded like the foundation for a solid investment. O’Neill, celebrated by Business-week as a “rock star” in the industry, looked for years like a vastly successful prophet. From 2001 to 2013, the economic output of the four BRIC countries rose from some $3 billion a year to $15 billion. The quartet’s growth, later made a quintet with the inclusion of South Africa (BRICS), was instrumental in protecting Western prosperity as well. Investors made a mint and O’Neill’s club even emerged as a real political power. Now, the countries’ leaders meet regularly and, despite their many differences, have often managed to function as a counterweight to the West.”The South has risen at an unprecedented speed and scale,” reads the United Nations Human Development Report 2013, completed just a few months ago. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote in his 2011 book “Civilization: The West and the Rest” of “the end of 500 years of Western predominance.” It is, he suggested, an epochal change. But now, after having become so used to success in recent years, reality has begun to catch up to the BRICS states. Growth rates in 2013 were far below where they were at their high-water marks. Whereas China’s growth rate reached a high of 14 percent just a few years ago, for example, it topped out at just 8 percent last year. In India, economic expansion fell from a one-time apex of 10 percent to less than 5 percent in 2013; in Brazil growth went from a high of 6 percent to 3 percent. Such values are still higher than those seen in the EU, but they are no longer as impressive. And worry is spreading. Now, there is a new moniker being used to describe the developing giants: the “fragile five.” It was coined by James Lord, a currency expert at Morgan Stanley and is meant as a warning to the now brittle-seeming countries of Brazil, India and South Africa as well as to Turkey and Indonesia, both of which are threatened with collapse.

Slow-Down or the End? What has happened? Have the economic climbers reached the end of their tethers or is it merely a temporary slow-down? Some have warned of overreacting, but the development raises questions for the global economy and for the people in those countries where economic success went at least partially hand-in-hand with increased political freedoms and a new self-confidence. The bad news is quickly mounting. On Tuesday of last week, India’s central bank raised interest rates higher than expected in an effort to get massive inflation under control. That night, Turkey did the same thing, raising its prime lending rate to 10 percent. Soon thereafter, South Africa followed with an increase of its own. Developing countries have become uneasy and are doing all they can to slow investor flight and the collapse of their currencies. Indeed, it almost seems as though the supposed decline of the West was but an illusion. In recent years, hundreds of billions was invested in the sovereign bonds of developing nations because returns in the established Western markets were comparatively weak. But last May, it took just a few words from then-Federal Reserve head Ben Bernanke to reverse the flow. He hinted that the US central bank could begin pumping less money into the financial system if the American recovery continued. A first wave of investors fleeing the developing world was the result.It took just half a year before Bernanke made good on his pledge. Now that the Fed has in fact begun to tighten monetary policy, a second wave has begun — and it is nothing short of a tsunami. Increasing numbers of investors have begun pulling out of uncertain markets in the belief that US growth and climbing interest rates are a sure thing. Since Bernanke’s announcement, Brazil’s real, the Turkish lira and the South African rand have lost up to a quarter of their value. It is an extremely dangerous development for the countries affected, particularly for those that import more than they export like India and Brazil. The gap, after all, must be filled with money from abroad. That may explain why Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff unabashedly courted international investors at the World Economic Forum in Davos in mid-January. Addressing bankers and captains of industry as if it were some kind of IPO road show, Rousseff said emerging economies like Brazil “have the biggest investment opportunities.” She said her country had sufficient currency reserves and that the financial system is stable enough to weather the current storms. The president argued it would be a mistake to only pay attention to short-term developments. It is “absolutely essential,” she said, “to bear in mind a medium and long-term time horizon in our reviews.”

Emerging Middle Classes Find Their Voice. It isn’t just the raw figures that are fueling concern among the governments of developing nations. From Beijing to New Delhi to Rio, the upswing has fostered a new self-awareness in people, creating a broad popular movement in the truest sense of the term. In recent years, impressive middle classes have taken shape in virtually all of the emerging economies. Members of that middle class are now demanding a larger piece of the pie and higher wages. At the same time, they also want “good governance” — meaning greater responsibility and accountability for their leaders — and the right to increased democratic participation. Economic progress has served as catalyst for political demands. If that dream now suddenly ends, it could also slam the brakes on these emerging popular movements — or at least stir emotions in dangerous ways. This is particularly true of Brazil, a country that has made major social progress in recent years. Unemployment is down as a result of the boom and the country’s support programs for the poorest segment of society have been largely successful. It may be happening slowly, but in contrast to many other countries around the world, the gap between the rich and poor is actually narrowing in Brazil. Still, the people want more. They are conscious of corruption among leaders and the ruling class; they are outraged when they see money wasted on lavish construction projects like the ones underway for the upcoming World Cup in the country. Indeed, it seems a paradox. Brazil is crazy for football and sports in general, but they are protesting against this summer’s World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics because they have come to realize that there are more important things in life than flashy stadiums. They want things like better schools for their children and decent, affordable health insurance. As a left-leaning social democrat, Rousseff has no other choice than to back the protests as long as they remain peaceful — and offer some kind of relief. Of course, that can only happen if she can keep Brazil’s economy from faltering.

Raw Nerves in India. The situation in India is worse. Nepotism has become endemic and a part of the ruling class is criminal. Nearly one-third of all parliamentarians are the subjects of criminal proceedings. The country has become one where cities with universities and world-class firms exist next to shockingly underdeveloped towns and villages. The numerous cases of rape suggest that women are still viewed as second-class citizens. Meanwhile, regional differences continue to grow. Nevertheless, civil society has also been strengthened in India as a result of the boom, and mass protests have forced the government to act. Thus far, the economy has managed to remain stable and business leaders are hoping that it will start growing again after elections this fall. Narendra Modi, the leading candidate for the Hindu nationalist BJP party, is viewed as an effective, business-friendly politician. At the same time, he is also seen as being insensitive towards minorities because of his role in bloody anti-Muslim riots. Critics accused Modi of inaction as the chief government minister in the state of Gujarat during the deadly protests in 2002. Hundreds of people, mostly Muslim, were killed, and the United States responded by banning him from entering the country. Indian Central Bank chief Raghuram Rajan is a good example of just how raw nerves in New Delhi have become. He has accused the US and Europe of short-sighted economic greed and argues that industrialized nations must assist developing countries with their currency problems — especially given that India, China and Co. helped dampen the crisis in 2008. “Industrial countries have to play a part in restoring that, and they can’t at this point wash their hands off and say we’ll do what we need to and you do the adjustment,” Rajan told Bloomberg TV in an interview earlier this month.

Concerns about Chinese Economy. One worry shared leaders of both BRICS states and Western countries alike is the possibility of an economic collapse in China. Last year China became the world’s greatest trading power. Within five years at the latest, China will likely surpass the United States to become the world’s No. 1 economy. But the country still faces plenty of challenges, particularly the next, more difficult level of development. After all, the step from the global poorhouse to the middle class is an easier one than climbing the next few rungs to the top. The droves of inexpensive workers who abandoned China’s agricultural sector and were absorbed by industry — thus transforming the country into the world’s factory — are now becoming a burden. They are beginning to demand higher wages and the state must provide for healthcare and pensions. China’s economic model, its authoritarian state-controlled capitalism, is being pushed to its limits. In order to reach the next level of development, the Communist Party will likely have to adopt Western state structures. The unspoken deal between leaders and their people — we ensure rising prosperity as long as you don’t get too involved in politics — is threatening to collapse. In addition to creating instability among 40 percent of the global population, a significant worsening of the economic situation in the BRICS countries could have significant consequences for the West. Global German companies like BASF and Siemens now generate a significant portion of their profits in the Far East. Volkswagen sells more cars in China than in Germany. Despite all of the problems with troubled banks and highly indebted municipalities, China still has some $3.8 trillion in currency reserves, more than any other country worldwide. It is certainly enough to soften the blow and likely sufficient to finance a rapid recovery in the event of a crisis.

Jim O’Neill, who coined the term BRICs while an investment banker with Goldman Sachs has embarked on a new path. He quit his job at the investment bank last April and now believes that the global economy finds itself at something of a divide. It is not so much one that runs between industrialized countries and the developing world so much as between the global rich and poor. He speaks of the headlines made by the pope and by New York’s new mayor with their speeches focusing on income inequality and growing societal splits. He believes that we could be in the early stages of a redistribution of wealth, one which places less emphasis on capital and more on climbing incomes among the lower classes, propelled by taxes or minimum wage laws. And, he adds, “we as investors” clearly have to take such developments into account. But also as human beings.