Government/Policy

January 5, 2021

Leibowitz on Trade: “Not Completely Bereft of Logic”

Written by Lewis Leibowitz

Eyes often glaze over when trade lawyers talk about the intricacies of antidumping law to what lawyers sometimes patronizingly call “laymen.” With a clear understanding of that risk, today’s piece dives into a recent decision by the Court of International Trade dealing with the Commerce Department’s treatment of Section 232 duties on steel in antidumping cases that should be of considerable interest to U.S. importers and traders of steel and aluminum, and of other products that may be subject to “national security” duties.

About half of antidumping duty orders are imposed on steel products. The duties are assessed on the difference between the “normal value” of covered product and the U.S. price paid for the goods (this is very much oversimplified to focus the reader on today’s issue).

Under the unique U.S. system of “retrospective” assessment of these duties, the amount of the antidumping duty will not be finally determined until years after the import shipment. The cash deposit paid at entry is just a down payment and may not be the final antidumping duty. These deposits are held by Customs. If the specific import sales are reviewed later, Commerce will calculate the final duties, which can go up or down based on the Commerce determination of the U.S. price (“export price”) and normal (foreign) value of each sale. Then Commerce instructs U.S. Customs to assess the final duties on the shipments based on the results of the review. If the final duty is higher than the amount deposited, Customs will collect the difference. If the final duty is lower, Customs will refund the difference.

When Commerce calculates the antidumping margin on these sales, the agency will “adjust” the prices. One adjustment is to reduce the U.S. price side of the equation by the amount of “import duties” before that price is compared to normal value.

Antidumping duties are not deducted from the export price, because they are not available until the review is completed, and because deducting antidumping duties from a calculation of antidumping duties would multiply the duties illogically. When the “safeguard” duties on steel went into effect, Commerce determined not to deduct those duties (Section 201 duties) from the U.S. price, rejecting arguments from domestic steel interests advocating the deduction.

The Court of International Trade case last week sustained a Commerce decision declaring that Section 232 duties should be deducted from the U.S. price. Commerce reached this decision in 2019 in an antidumping review of carbon steel welded pipe during the Trump administration. Importers in the review argued that Commerce should follow the Section 201 precedent and not deduct Section 232 duties from the U.S. price, but Commerce disagreed. The importers challenged this decision by filing suit in the Court of International Trade.

In its opinion, the court reviewed the Commerce determination to treat Section 232 duties differently from Section 201 duties. Commerce looked at three factors—(1) whether they are “remedial,” (2) whether they are “temporary”, and (3) whether deducting the duties would result in a “double remedy,” or a doubling of duties. In treating Section 232 duties differently from the earlier decision on Section 201 duties, Commerce concluded, first, that Section 232 duties differ from Section 201 duties because the former, unlike the latter, are not “remedial.” They are based on national security grounds rather than helping the affected domestic industry adjust to the realities of import competition.

Concerning the second factor (whether the duties are “temporary”), Commerce determined that, because the president could only impose the duties for a maximum of five years under Section 201, and Section 232 duties could (but need not) last forever, Section 232 was not “temporary.”

Finally, Commerce decided that double counting, which is obvious in deducting Section 201 and 232 duties, nevertheless does not preclude this step because, unlike the interplay between calculating antidumping duties and Section 201 duties, there is no connection between the calculation of Section 232 duties and antidumping duties.

The court affirmed Commerce’s determination under a long-standing rule that courts must sustain “expert” agency determinations of a statute if it is “reasonable.” There, the court cut an unusual amount of slack for the agency, concluding that Commerce’s determination met (but obviously not by much) the standard of reasonableness on each of the three factors.

First, the court sustained the Commerce decision on Section 232 duties because its reasoning “based on lack of remedial purpose [of Section 232], while not the strongest, is not completely bereft of logic.” Faint praise indeed. The court went on to sustain Commerce’s conclusion that the Section 232 duties were not “temporary” because there was no statutory limit on how long they could last. Finally, the court did not discuss the obvious double-counting of duties resulting from the decision except to say that there was no congressional instruction not to double-count Section 232 duties and antidumping duties. In short, because Congress did not prohibit it, Commerce was within its authority to double-count.

The court’s approval of double-counting Section 232 duties, for importers of products subject to antidumping duties, is economically consequential. The antidumping law requires importers of record to pay all applicable duties (and duty deposits) under antidumping orders and Section 232 proclamations (and duty deposits) to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. This decision will increase their liability.

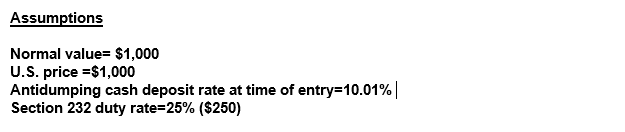

What follows is a brief (and necessarily oversimplified) example of the consequences of this decision:

Before Commerce decided to deduct Section 232 duties from the U.S. price, an importer would pay a $100 cash deposit on this shipment. After the review of this shipment (2-3 years on), the final antidumping duty would be assessed at zero, and the importer would receive a refund of the $100 cash deposit paid at the time of entry (plus interest).

After the Commerce decision: The cash deposit two or three years earlier remains $100, but after the deduction of Section 232 duties the U.S. price falls to $750, creating an antidumping duty of $250 on this shipment where none existed before. Instead of a refund, the importer will get a bill from U.S. Customs for $150 ($250 minus the $100 cash deposit).

To add to the burden, the review will also calculate a new antidumping cash deposit rate for importers based on all shipments reviewed. If the example is used, a new average margin of $250 for that entry, or a percentage rate of 25% ($250/$1,000). The cash deposit on future entries would go from 10% to 25%.

The cost of duties would travel from importers to downstream consumers of steel and aluminum, based on market economics. Since most antidumping cases on steel also have the 25% Section 232 duty, this effect will be widespread.

The Commerce decision to deduct Section 232 duties from the U.S. price in antidumping cases was made in 2019, during the Trump administration. The Biden administration, which did not make the decision, might (or might not) reconsider whether this is the right answer for the country. Either way, this decision has serious consequences for importers of steel and aluminum products and provides no direct economic benefit to steel or aluminum producers because all the extra money will go to the U.S. Treasury.

It’s too early to say whether this decision will be appealed to a higher court, but it would not surprise me to see it.

This development bears watching.

The Law Office of Lewis E. Leibowitz

1400 16th Street, N.W.

Suite 350

Washington, D.C. 20036

Phone: (202) 776-1142

Fax: (202) 861-2924

Cell: (202) 250-1551