Market Data

October 11, 2020

CRU: U.S. Recovery to Shift Down a Gear

Written by Anissa Chabib

By CRU Economist Anissa Chabib, from CRU’s Global Steel Trade Service

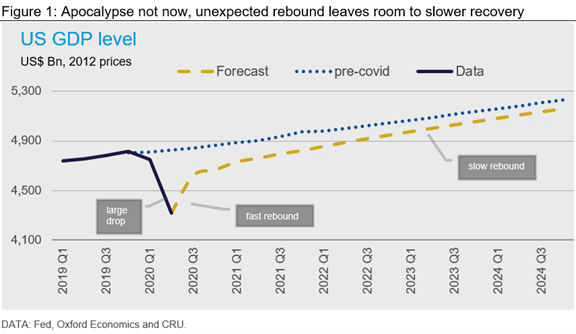

2020 has seen an unusual recession that was brought on by a pandemic. To match this, the shape of the recovery is likely to be equally unusual. The U.S. recovery is starting to lose momentum, with more slowing to come in 2021. Large uncertainties lie ahead that could derail the recovery, the path of the virus and the outcome of the U.S. election. The good news is that metal end-use sectors have fared relatively well—residential construction has remained resilient, and auto demand is returning quickly. Prospects for the non-residential sector, however, look weaker than the residential sector.

Depth of Recession and Pace of Recovery Have Been Unique

This recession is obviously very different to previous recessions in that the underlying shock is a pandemic. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell describes it well when he repeatedly says that “the path of the economy will depend significantly on the course of the virus.”

When the U.S. entered lockdown, businesses had to close and households had to stay home. This prevented people from consuming and companies from fulfilling business operations. Putting the economy “on pause” led to a major fall in economic activity in Q2 2020. The drop in GDP was almost 2.5 times deeper than the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), and six times faster.

When states started to reopen, the U.S. economy demonstrated a fast and better-than-expected rebound. Three main factors can explain such a strong recovery:

• Large fiscal stimulus (U.S. $2.3 trillion, around 11 percent of GDP)

• Flexible labor market, helping the economy to add jobs quickly

• Release of pent-up demand that had built up during lockdown

Looking forward, the recovery will be slower. We expect U.S. GDP to fall by 3.8 percent y/y in 2020 and grow by 4.1 percent in 2021. We also expect GDP to return to pre-pandemic levels in Q3 2021. A slower recovery from here on is partly the result of continued uncertainty about future job and growth prospects. This uncertainty will weigh on consumption and business investment. Moreover, the effects of the factors propping up demand thus far—pent-up demand and fiscal stimulus—are already fading.

Overall, the shape of the recession displays three key features: first a deep fall, then a quick rebound and finally a slow long recovery. We define this profile as a U-shaped recovery (Figure 1).

Return to Pre-Covid-19 Levels from 2021

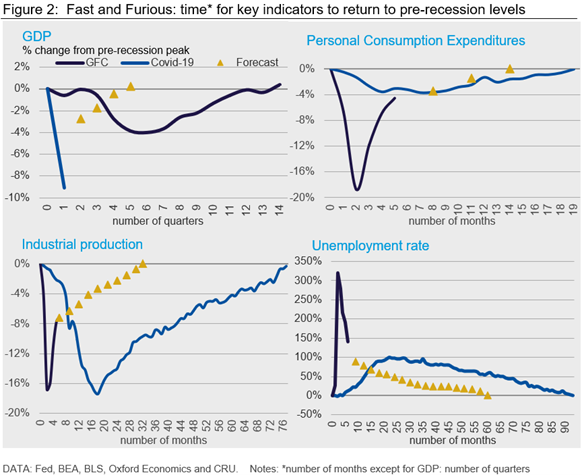

The sharp rebound in the U.S. economy thus far has led to speculation about when the economy will return to pre-Covid-19 levels. The charts below (Figure 2) show the speed of this relative to the experience of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

As noted above, in our forecast, GDP (yellow triangles) is expected to return to pre-Covid-19 levels in five quarters, in Q3 2021. During the pandemic, the fall in GDP was tremendously fast, taking only two months to reach the trough, while it took six quarters during the GFC.

Looking at the drivers of the recession, U.S. personal consumption fell sharply but quickly bounced back. Again, the path during the GFC was much slower on the way down as well as on the way up. We expect consumption to go back to pre-recession levels after 14 months, in Q2 2021. Consumption is now slowing due to uncertainties about the future, including job prospects, decreasing personal income (-2.7 percent m/m in August), fading unemployment insurance benefits (weekly supplemental payment of $600 expired on July 31) and social distancing that will be endured for longer than expected.

The peak to trough drop in industrial production (IP) was -17 percent during the GFC, and took 1.5 years. The identical peak to trough drop in IP during the pandemic took only two months. We forecast IP to return to pre-Covid-19 levels by the end of 2022. The recovery in IP is slowing as it is following demand.

The unemployment story is similar; the unemployment rate rocketed to 14.7 percent in April, returning to 7.9 percent in just five months. We believe the unemployment rate will fall to 5.8 percent in 2021, and below 5 percent by Q2 2022. It is expected to return to the pre-Covid-19 rates of 3.8 percent by 2025.

Worrying Signs in the Labor Market Threatens Spending

It is very clear that after a strong recovery the economy is now losing momentum. For example, the pace of recovery in retail sales and consumer sentiment has started to slow. In August, retail sales rose by only 0.6 percent m/m, personal income decreased by 2.7 percent m/m and consumer spending grew by only 1 percent m/m.

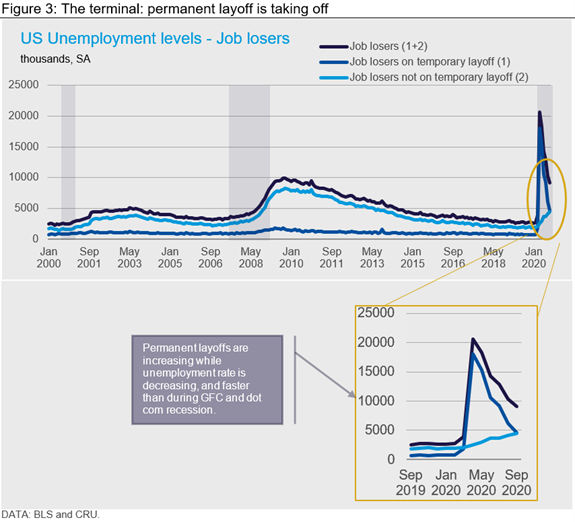

Due to the pandemic, 20 million people lost their jobs in April. The sheer volume of these job losses has thrust the labor market into the spotlight. Although the fall in the headline unemployment rate has been impressive, if we look below the surface there are some worrying signs. First, the rise in unemployment is unprecedented relative to the past two recessions shown on the chart: the dot com recession and the GFC (shaded areas).

Second, the chart shows that while the number of people on temporary layoff has continued to fall, the number of permanent layoffs is increasing, faster than during previous recessions. This is concerning. Should this trend continue, the unemployment rate is likely to stay high for longer. This is because it typically takes longer for those on permanent layoff to find jobs. It also means that businesses are implementing irreversible changes such as closing down or definitively cutting staff in the medium to long run. This will negatively impact consumption (e.g. spending on autos and housing) and overall economic activity. The need of a second fiscal stimulus, expected after the presidential election and including extended UI benefits, is necessary to avoid consumer spending dropping again.

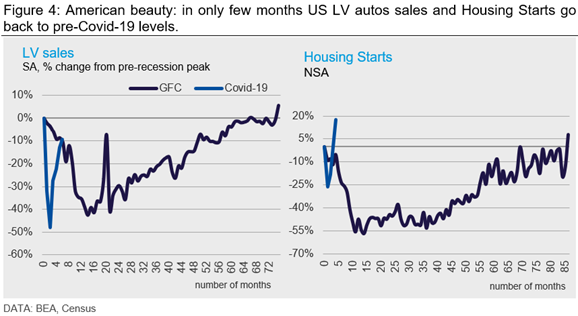

Construction Resilient; Autos Recover Faster Than Expected

Residential construction has been resilient over the past six months. Housing starts dropped from 1.25 mn saar in March to 0.9 mn saar in April, but rebounded to 1.4 mn saar in August, i.e. above pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4). This fast rebound despite poor economic conditions is mainly explained by the fact that households suffering most severely from unemployment constitute only a small proportion of the new homeownership pool. Home buyers tend to be higher-wage workers, who have retained their jobs and benefitted from the government stimulus checks and record low mortgage rates. We expect broad stability around the current level as housing starts remain stable into 2021.

To date, non-residential construction has not drastically fluctuated. However, social distancing restrictions have given rise to increased working from home and a fall in retail footfall. This has pushed up property vacancy, led to a contraction in commercial real estate sales, and slowed the increase in rent. The recession has also put pressure on state level finances that will reduce state investment into new buildings in 2021. In August, the Architecture Billings Index—a leading indicator of where the sector is heading—was at 40 for the third month running (anything below 50 is a contraction). This suggests commercial construction will remain on the decline as fewer companies will invest in new buildings. We expect the sector to weaken in H1 2021.

The auto sector has suffered a big blow. Total light vehicle sales (LV) fell from 16.8 mn saar units, to 8.7 mn saar units in February. This recovered to 15.2 mn saar in August, just shy of the pre-Covid-19 levels.

We forecast LV production to fall by 20 percent y/y in 2020, rising to 14.1 percent 2021. In our forecast, quarterly LV production returns to pre-Covid-19 levels by Q3 2020. The chances of a “cash for clunkers” scheme, however, appear low at this stage. This is not only because sales have been resilient, but also because a second stimulus package makes such a scheme less likely.

Conclusion

This crisis is distinctive because the exogenous shock to the economy is a global pandemic. The shape of the recovery is likely to be unusual—first a deep downturn, then a quick rebound followed by slow momentum. The U.S. recovery is already running out of steam and will continue to do so into 2021. This base case view assumes that the pandemic does not lead to further economic disruptions, and that a second federal stimulus will sustain the recovery next year. The availability of a vaccine, and the outcome of the U.S. presidential election are two important uncertainties that could either weigh or boost sentiment and economic activity in the future. The good news is that metal end-use sectors bounced back relatively well—residential construction has remained resilient, and auto demand is returning quickly.

Request more information about this topic.

Learn more about CRU’s services at www.crugroup.com