Market Data

September 8, 2020

Net Job Creation Through August: Only Halfway Back

Written by Peter Wright

Steel Market Update is please to share this Premium content with Executive members. For information on upgrading to a Premium-level membership, email Info@SteelMarketUpdate.com.

Nonfarm employment is improving, but made back less than half the losses seen in the two months of March and April in the four-month period from May through August.

![]()

The August jobs report was released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Friday and met consensus expectations by adding 1.4 million jobs. June and July were both revised down slightly. In May through August, 10.6 million jobs were created, just less than half the 22.2 million lost in March and April.

Figure 1 shows the total number of nonfarm employed people in the U.S. since 2000. The net loss since February’s all-time high result stands at 11.5 million.

Stated the BLS on Sept. 4: “Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 1.4 million in August, and the unemployment rate fell to 8.4 percent. These improvements in the labor market reflect the continued resumption of economic activity that had been curtailed due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and efforts to contain it. In August, an increase in government employment largely reflected temporary hiring for the 2020 Census. Notable job gains also occurred in retail trade, in professional and business services, in leisure and hospitality, and in education and health services.”

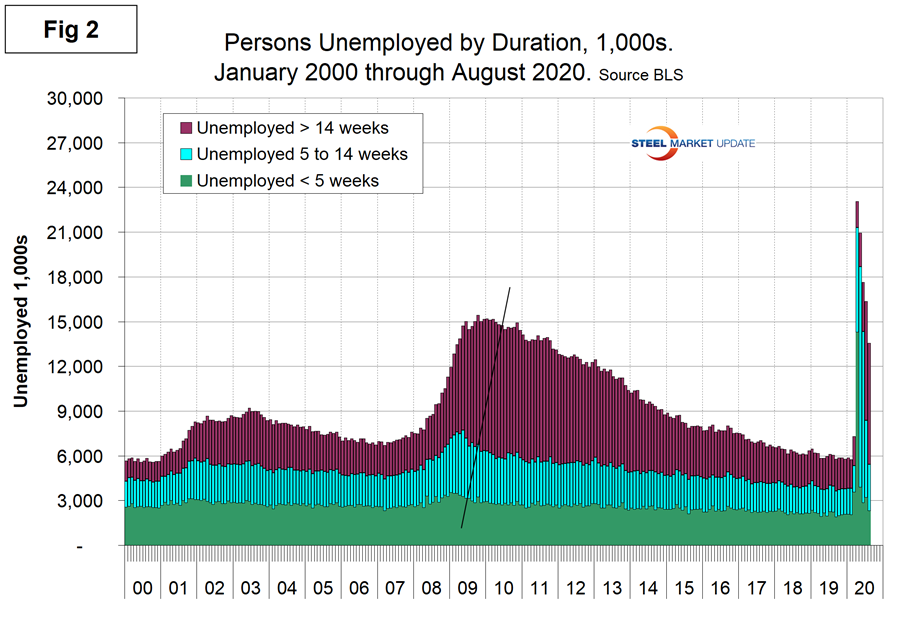

Figure 2 shows the historical picture for the duration of unemployment since January 2000 broken down into < 5 weeks, 5 to 14 weeks and > 14 weeks. The total number unemployed was 13,555,000 at the end of August, down from 23,059,000 at the end of April.

The official unemployment rate, U3, reported in the BLS Household survey (see explanation below) increased from 3.5 percent in February to 14.7 percent in April and declined to 8.4 percent in August. The more comprehensive U6 unemployment rate, at 14.2 percent in August, improved from 22.8 percent in April (Figure 3). U6 includes individuals working part time who desire full-time work and those who want to work but are so discouraged they have stopped looking.

The labor force participation rate is calculated by dividing the number of people actively participating in the labor force by the total number of people eligible to participate. This measure was 61.7 percent in August, up from 60.2 percent in April but down from 63.4 percent in January and February. Another gauge is the number employed as a percentage of the population, which we think is more definitive. In August, the employment-to-population ratio was 56.5 percent, up from the low point of 51.3 percent in April. Figure 4 shows both measures on one graph.

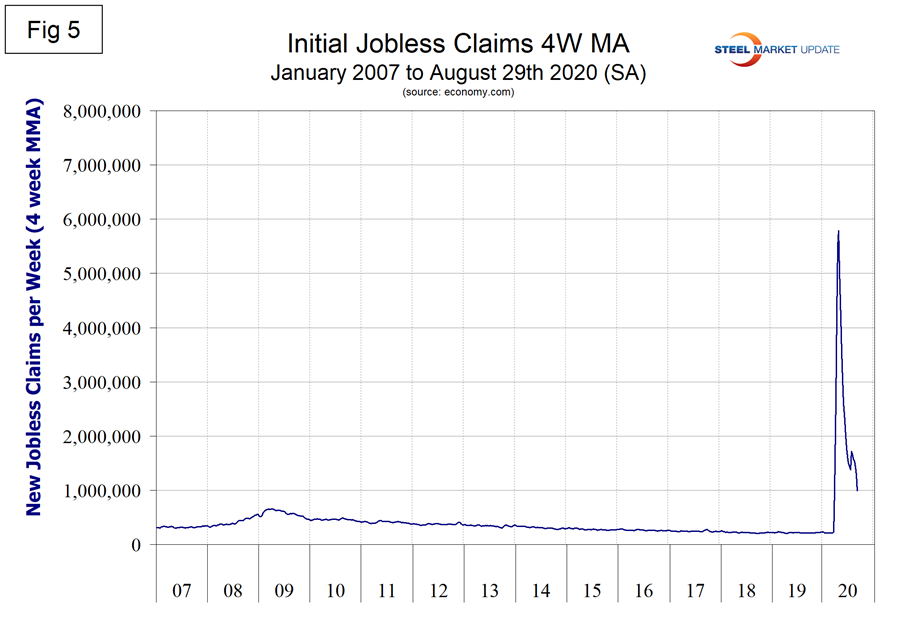

Initial claims for unemployment insurance, reported weekly by the Department of Labor, exploded in the two weeks ending March 21 and March 28 by a total of 6.6 million. Since then in the week ending Aug. 29, new claims have declined to 881,000. This improvement was partly due to revisions in the BEA’s seasonal adjustment procedure and in how new filings for pandemic unemployment assistance are processed. New filings are still much higher than they were at the peak of the Great Recession. Figure 5 shows the four-week moving average of new claims since January 2007.

Challenger, Gray and Christmas Inc. produces a monthly employment update for the U.S. and reported that job cuts in August decreased by 56 percent from July. As Challenger stated Sept. 3: “Job cuts announced by U.S.-based employers in August totaled 115,762, 116 percent higher than the August 2019 total of 53,480. August’s total is 56 percent lower than the 262,649 job cuts announced in July. It is the highest total in August since 2002 when 118,067 job cuts were announced. The leading sector for job cuts last month was transportation, as airlines begin to make staffing decisions in the wake of decreased travel and uncertain federal intervention. An increasing number of companies that initially had temporary job cuts or furloughs are now making them permanent.”

Figure 6 shows the monthly job cuts reported by Challenger on a 3MMA basis since January 2007.

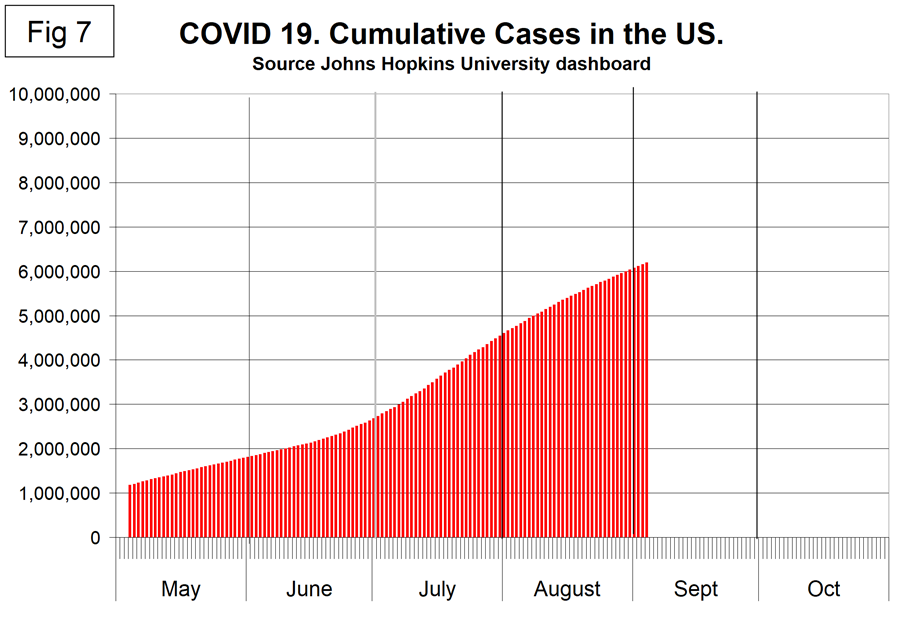

SMU Comment: February 2020 was the all-time high for nonfarm employment in the U.S. Since then the economy has given back all the gains that occurred since March 2015. The unemployment rate has improved, but is still dismal, and the root cause is flattening only slightly. Figure 7 shows the cumulative COVID-19 case count through Sept. 4. It appears that in many industries employment patterns may be changing permanently as companies adapt, learn and re-consider past practices.

Explanation: On the first Friday of each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the employment data for the previous month. Data is available at www.bls.gov. The BLS reports on the results of two surveys. The Establishment survey reports the actual number employed by industry. The Household survey reports on the unemployment rate, participation rate, earnings, average workweek, the breakout into full-time and part-time workers and lots more details describing the age breakdown of the unemployed, reasons for and duration of unemployment. It’s important to understand that none of these numbers is an actual count of everyone employed across the country. No one keeps comprehensive records, and they’re certainly not processed centrally on a monthly basis. All the reported numbers are based on samples of the population. At Steel Market Update, we track the job creation numbers by many different categories. The BLS database is a reality check for other economic data streams such as manufacturing and construction. We include the net job creation figures for those two sectors in our “Key Indicators” report. It is easy to drill down into the BLS database to obtain employment data for many subsectors of the economy. For example, among hundreds of sub-indexes are truck transportation, auto production and primary metals production. The important point about all these data streams is the direction in which they are headed. Whenever possible, we try to track three separate data sources for a given steel-related sector of the economy. We believe this gives a reasonable picture of market direction. The BLS data is one of the most important sources of fine-grained economic data that we use in our analyses. The states also collect their own employment numbers independently of the BLS. The compiled state data compares well with the federal data. Every three months, SMU examines the state data and provides a regional report, which indicates strength or weakness on a geographic basis. Reports by individual state can be produced on request.