Market Data

November 5, 2019

Net Job Creation Through October 2019

Written by Peter Wright

The rate of job creation in October slowed, partly due to the GM strike. Net job creation in October declined to 128,000 from an upwardly revised 180,000 in September. August was revised up by 51,000 and September up by 44,000. In combination, this was the highest upwards two-month revision that we can remember.

Rising employment and wages are the main contributors to GDP growth because personal consumption accounts for almost 70 percent of GDP. Steel consumption is related to GDP; therefore, this is one of the indicators that help us understand the reality of the steel market.

![]()

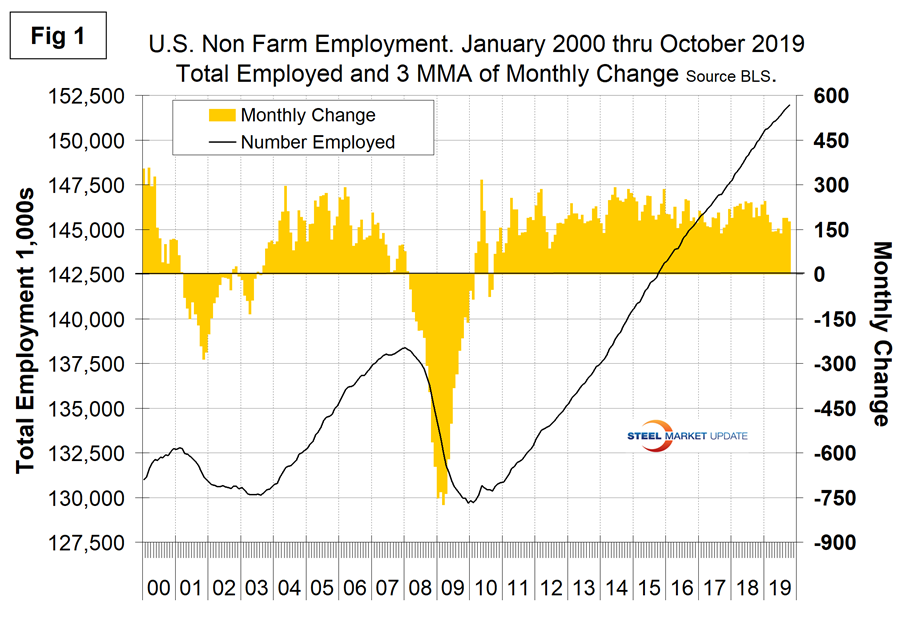

Figure 1 shows the three-month moving average (3MMA) of the number of jobs created monthly since 2000 as the brown bars and the total number employed as the black line. Economy.com reported as follows: “The U.S. labor market did even better than it appears in October, and there is nothing not to like in the employment report. Nonfarm payrolls rose 128,000, better than either we or the consensus anticipated. There were also upward revisions to prior months. The gain in employment would have been even larger if not for the United Auto Workers strike that subtracted 42,000 from employment. The spillover effect appears to have been much smaller than anticipated. Also, layoffs of temporary Census Bureau workers reduced employment by 17,000. The unemployment rate increased from 3.5 percent to 3.6 percent, but it rose for all the right reasons. Average hourly earnings were up 0.2 percent between September and October. All told, the job market is in good shape, and odds of a Fed rate cut in December are falling.”

We prefer to use three-month moving averages in our analyses to reduce short-term variability. In averaging employment statistics in this way, we even out what is notoriously volatile data.

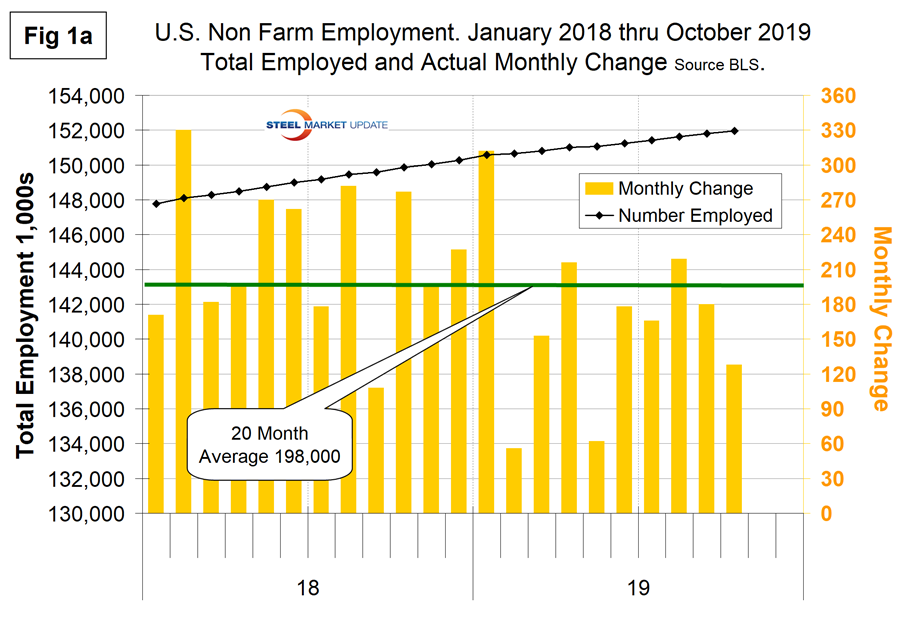

Figure 1a shows the raw monthly data since January last year and that the variability has been worse in 2019 than it was in 2018. The average monthly job creation in the last 22 months has been 198,000. In 2018, the average rate of job creation was 223,300 per month. In the first 10 months of 2019, the average monthly rate was 167,000 jobs.

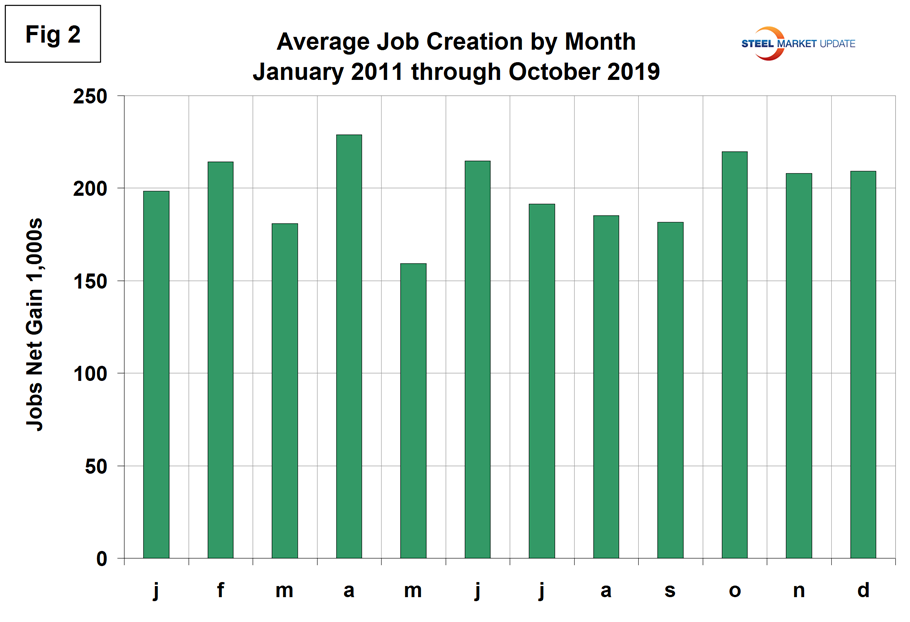

The employment data has been seasonally adjusted. We have developed Figure 2 to examine if any seasonality is left in the data after adjustment. In the nine years since and including 2011, the average month-on-month change from September to October has been positive 21.0 percent. This year the change was negative 29.0 percent, therefore worse than normal. Only about half of this discrepancy can be attributed to the GM strike, thus as Octobers go, this was not a good result. We think it’s significant to look at the results this way because there is so much variability in the numbers that a long-term context is necessary and it doesn’t look as though the BLS seasonal adjustment is very effective.

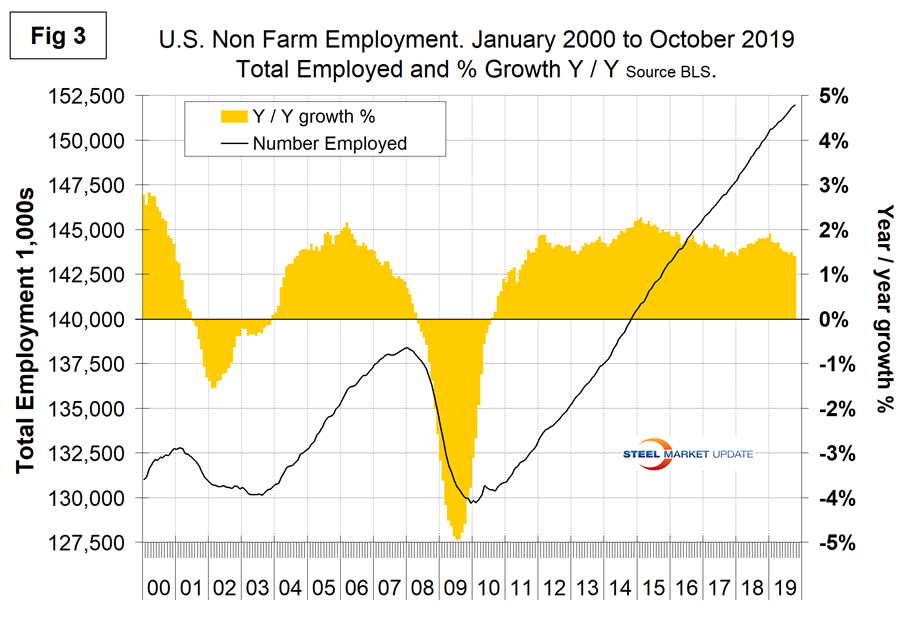

In order to get another look at the degree of change, we have developed Figure 3. This shows the same total employment line as Figure 1, but includes the year-over-year growth on a percentage basis and shows more clearly the steady improvement that occurred during 2018 and the slowdown in 2019. The year-over-year growth of the total number employed has slowed from 1.9 percent in January 2019 to 1.4 percent in October. Considering the variability of the raw monthly data, we think the year-over-year view is the best way to evaluate what’s really going on.

November 2018 was the first month ever for total nonfarm payrolls to exceed 150 million and in October 2019 was 151.945 million, which was 13.580 million more than the pre-recession high of January 2008.

According to the latest BLS economic news release for October, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 6 cents to $28.18. Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 3.0 percent. In October, average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 4 cents to $23.70. The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls was unchanged at 34.4 hours. In manufacturing, the average workweek decreased by 0.2 hour to 40.3 hours, while overtime was unchanged at 3.2 hours. The average workweek of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees held at 33.6 hours in October.

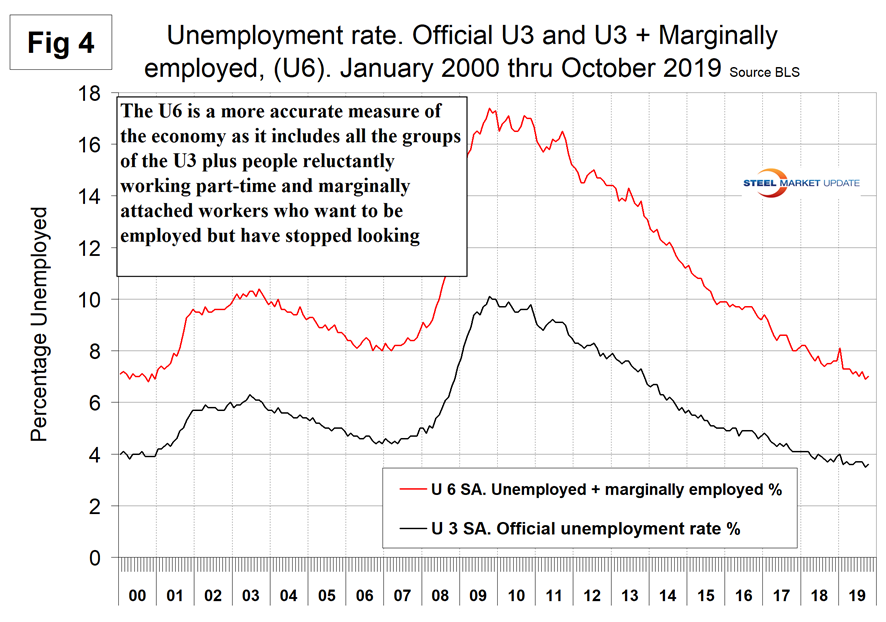

The official unemployment rate, U3, reported in the BLS Household survey (see explanation below) declined from 3.7 percent in June, July and August to 3.5 percent in September and 3.6 percent in October. U3 has ranged from 3.5 to 4.0 percent in each of the last 17 months. This is not a very representative number. The more comprehensive U6 unemployment rate at 7.0 percent was down from 8.1 in January (Figure 4). The difference between these two measures in September and October was 3.4 percent, which is historically excellent and the lowest since August 2001. U6 includes individuals working part time who desire full-time work and those who want to work but are so discouraged they have stopped looking.

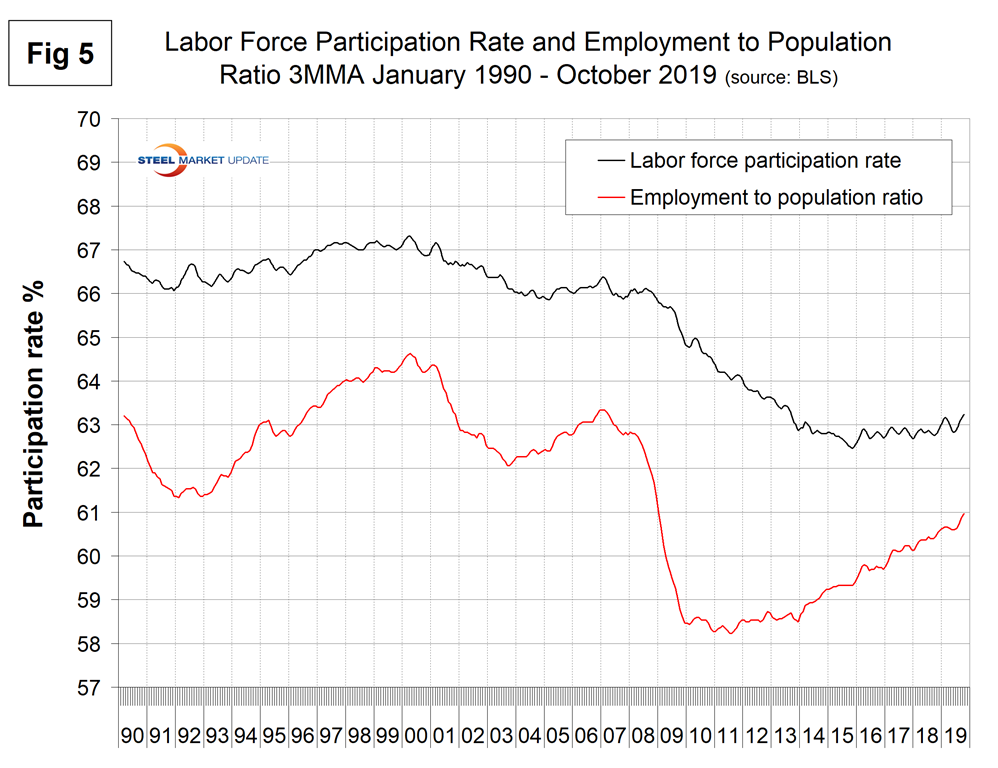

The labor force participation rate is calculated by dividing the number of people actively participating in the labor force by the total number of people eligible to participate. This measure was 63.2 percent in October and hasn’t changed much in three years. Another gauge is the number employed as a percentage of the population, which we think is more definitive. In October, the employment-to-population ratio was 61.0 percent, the highest since November 2008. Figure 5 shows both measures on one graph.

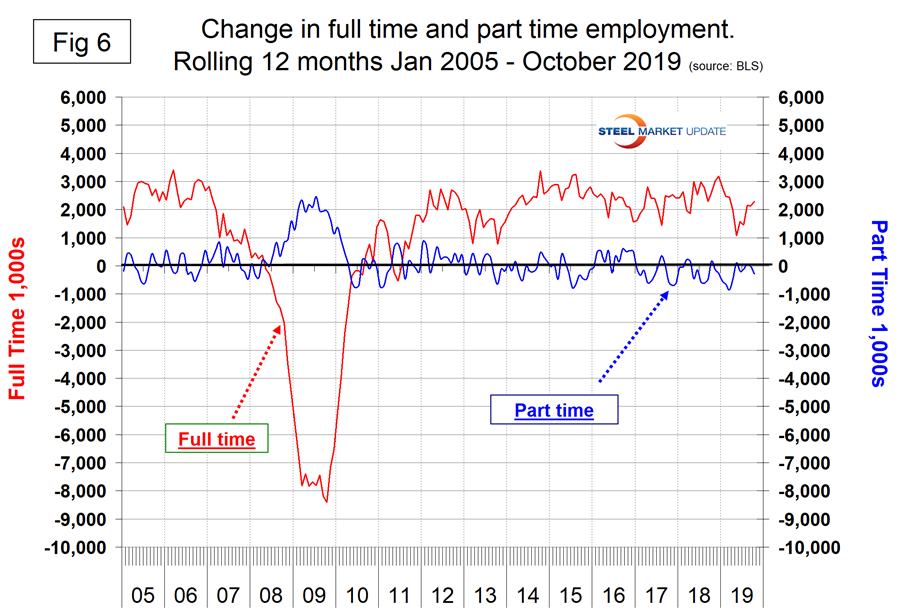

In the 46 months since and including January 2016, there has been an increase of 8,805,000 full-time and a decrease of 357,000 part-time jobs. Figure 6 shows the rolling 12-month change in both part-time and full-time employment. This data comes from the Household survey and part-time is defined as less than 35 hours per week. Because the full-time/part-time data comes from the Household survey and the headline job creation number comes from the Establishment survey, the two cannot be compared in any given month. To overcome the volatility in the part-time numbers, we look at a rolling 12 months for the full-time and part-time employment picture shown in Figure 6.

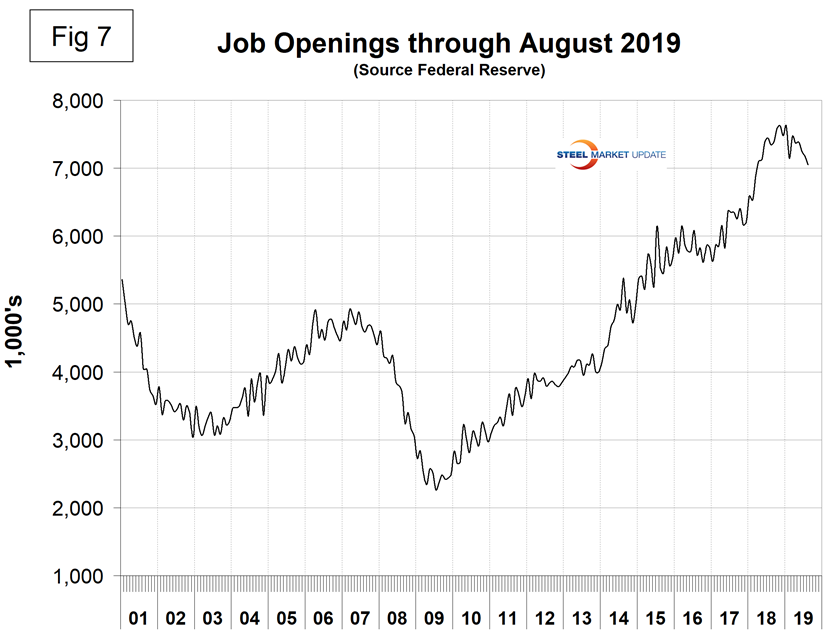

The job openings report known as JOLTS is reported on about the 10th of the month by the Federal Reserve and is over a month in arrears. In the October employment report, JOLTS data was reported for August. Figure 7 shows the history of unfilled jobs. In August, openings stood at 7,051,000, which was still historically high but down from 7,626,000 in November 2018. There are still more job openings than there are people counted as unemployed.

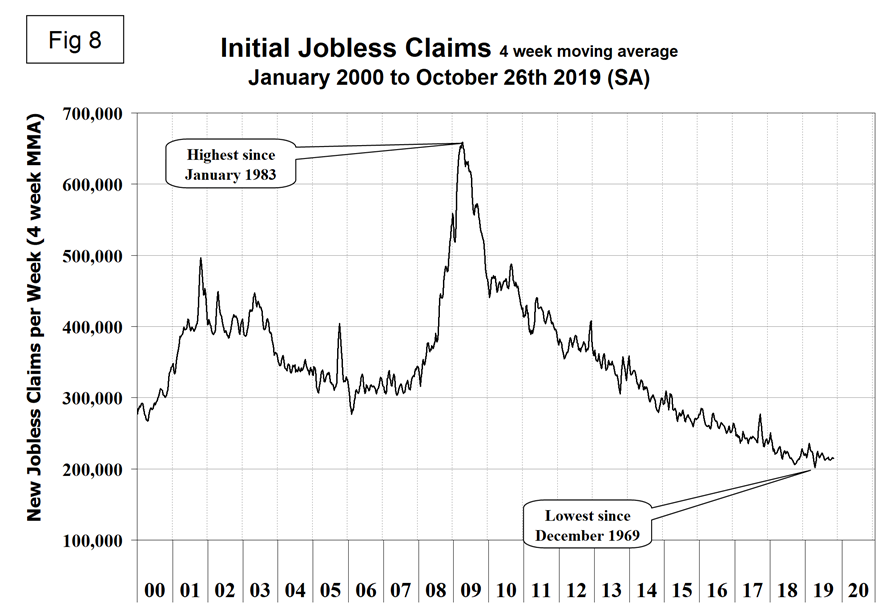

Initial claims for unemployment insurance, reported weekly by the Department of Labor, have been exceptionally low since 2014. The U.S. is enjoying the longest streak since 1973 of initial claims below 300,000 (Figure 8). This data stream is part of our recession outlook report and at present shows no sign of an imminent problem.

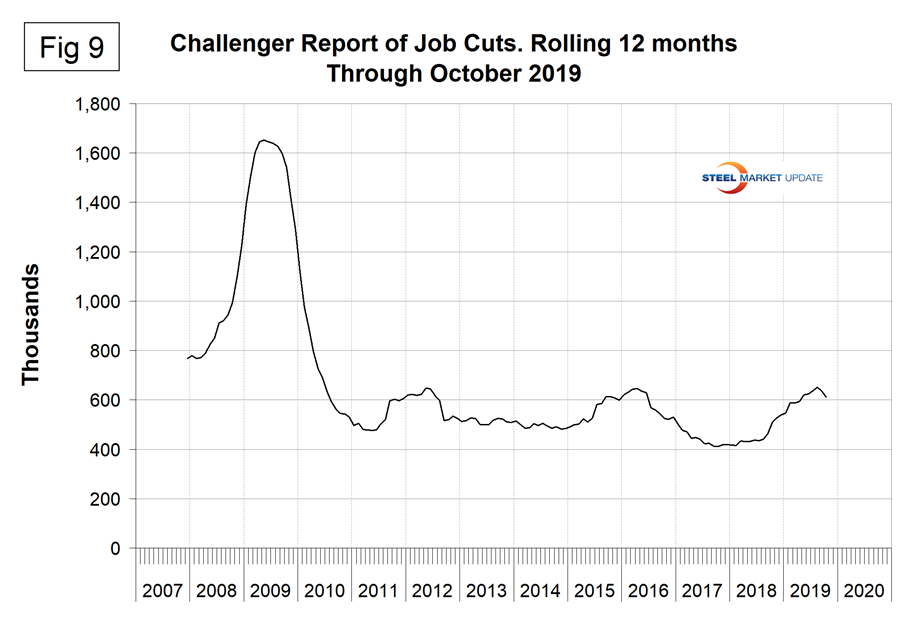

Challenger Grey and Christmas Inc. produces a monthly report of job cuts in the U.S. Job cuts were 50,300 in October, which was up from September, but the rolling 12-months total has declined for the last two months (Figure 9). Economy.com reported: “Technology and retail topped the industry list in terms of most layoffs. Firms reported branch closings and restructuring as the most prevalent reasons for job cuts in October. Announced hiring plans were lower than last month but stronger than a year ago.”

SMU Comment: This report was mixed. Evidently it exceeded economists’ expectations and the upward revisions for August and September were unusually high. Nevertheless, even after taking the GM strike into account, this was a poor result by October standards. There is no doubt that the job market has slowed this year.

Explanation: On the first Friday of each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the employment data for the previous month. Data is available at www.bls.gov. The BLS reports on the results of two surveys. The Establishment survey reports the actual number employed by industry. The Household survey reports on the unemployment rate, participation rate, earnings, average workweek, the breakout into full-time and part-time workers and lots more details describing the age breakdown of the unemployed, reasons for and duration of unemployment. At Steel Market Update, we track the job creation numbers by many different categories. The BLS database is a reality check for other economic data streams such as manufacturing and construction. We include the net job creation figures for those two sectors in our “Key Indicators” report. It is easy to drill down into the BLS database to obtain employment data for many subsectors of the economy. For example, among hundreds of sub-indexes are truck transportation, auto production and primary metals production. The important point about all these data streams is the direction in which they are headed. Whenever possible, we try to track three separate data sources for a given steel-related sector of the economy. We believe this gives a reasonable picture of market direction. The BLS data is one of the most important sources of fine-grained economic data that we use in our analyses. The states also collect their own employment numbers independently of the BLS. The compiled state data compares well with the federal data. Every three months, SMU examines the state data and provides a regional report, which indicates strength or weakness on a geographic basis. Reports by individual state can be produced on request.