Analysis

August 2, 2019

SMU Analysis: State and Locally Funded Construction Continues to Boom

Written by Peter Wright

Private construction contracted in three months through June, but state and locally funded work, including infrastructure, is continuing to boom.

Construction Put in Place (CPIP) expenditures data for June was released on Aug. 1. Through June, total construction has had negative momentum every month since October last year. This was entirely a result of contracting privately funded work. Infrastructure and state and locally funded projects are booming, according to Steel Market Update’s analysis of Commerce Department data

![]()

At SMU, we analyze the CPIP data to provide a clear description of activity that accounts for about 45 percent of total U.S. steel consumption. See the end of this report for more detail on how we perform this analysis and structure the data. The growth or contraction that we report in this analysis has had seasonality removed by providing only year-over-year comparisons.

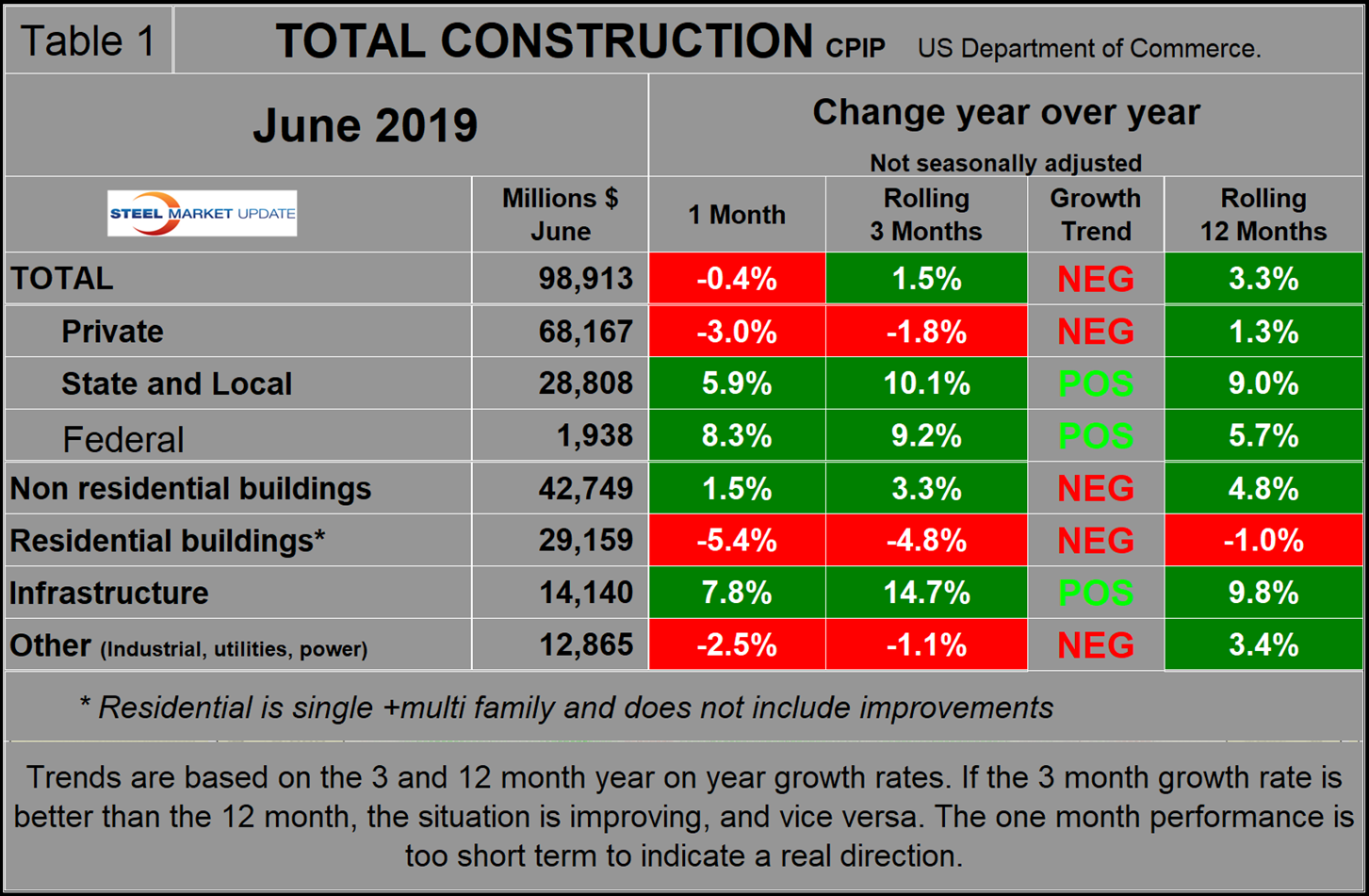

Total Construction

Total construction expanded by 1.5 percent in three months through June and by 3.3 percent in 12 months through June, both year over year. Since the three-month growth rate is lower than the 12-month rate, we conclude that momentum is negative. June construction expenditures totaled $98.9 billion, which breaks down to $68.2 billion of private work, $28.8 billion of state and locally funded (S&L) work, and $1.9 billion of federally funded work (Table 1). Growth trend columns in all four tables in this report show momentum.

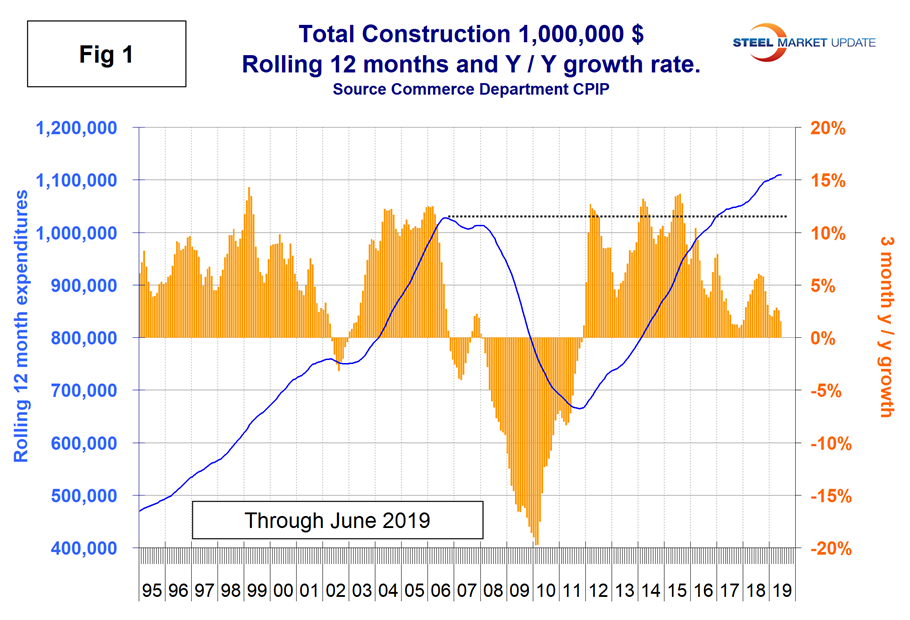

Figure 1 shows total construction expenditures on a rolling 12-month basis as the blue line and the rolling three-month year-over-year growth rate as the brown bars. Total construction in the 12 months through June was at an all-time high, but the brown bars show growth is lackluster.

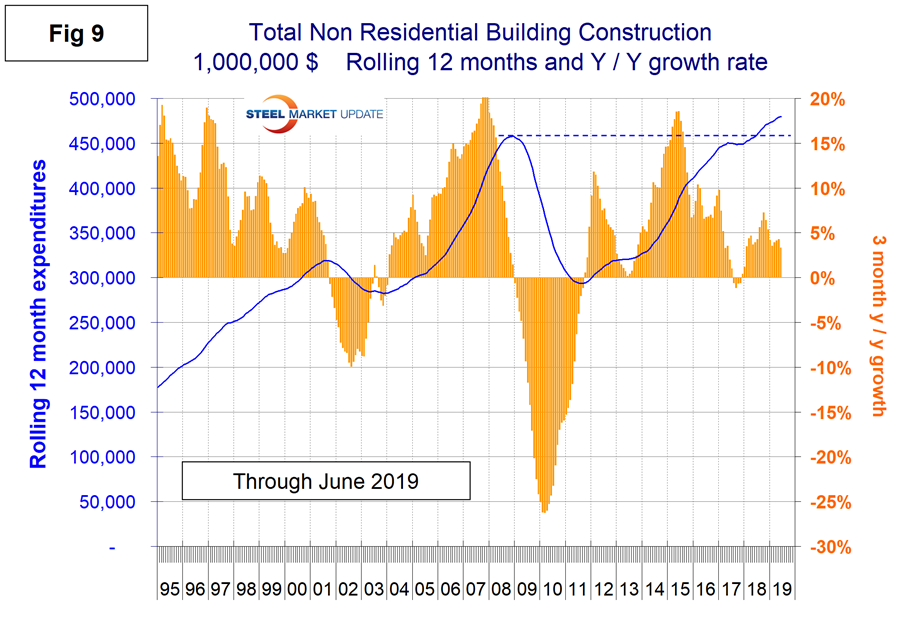

Figures 1, 2, 6, 7 and 9 in this analysis have the same format, the result of which is to smooth out variation and eliminate seasonality. We consider four sectors within total construction: nonresidential, residential, infrastructure and other. The latter is a catchall and includes industrial, utilities and power. Of these four sectors, S&L, infrastructure and federal had positive momentum in June.

The pre-recession peak of total construction on a rolling 12-month basis was $1.028 trillion through November 2006. The low point was $665.1 billion in the 12 months through March 2011. In 12 months through June 2019, construction expenditures totaled $1.109 trillion. (This number excludes residential improvements; see explanation below.)

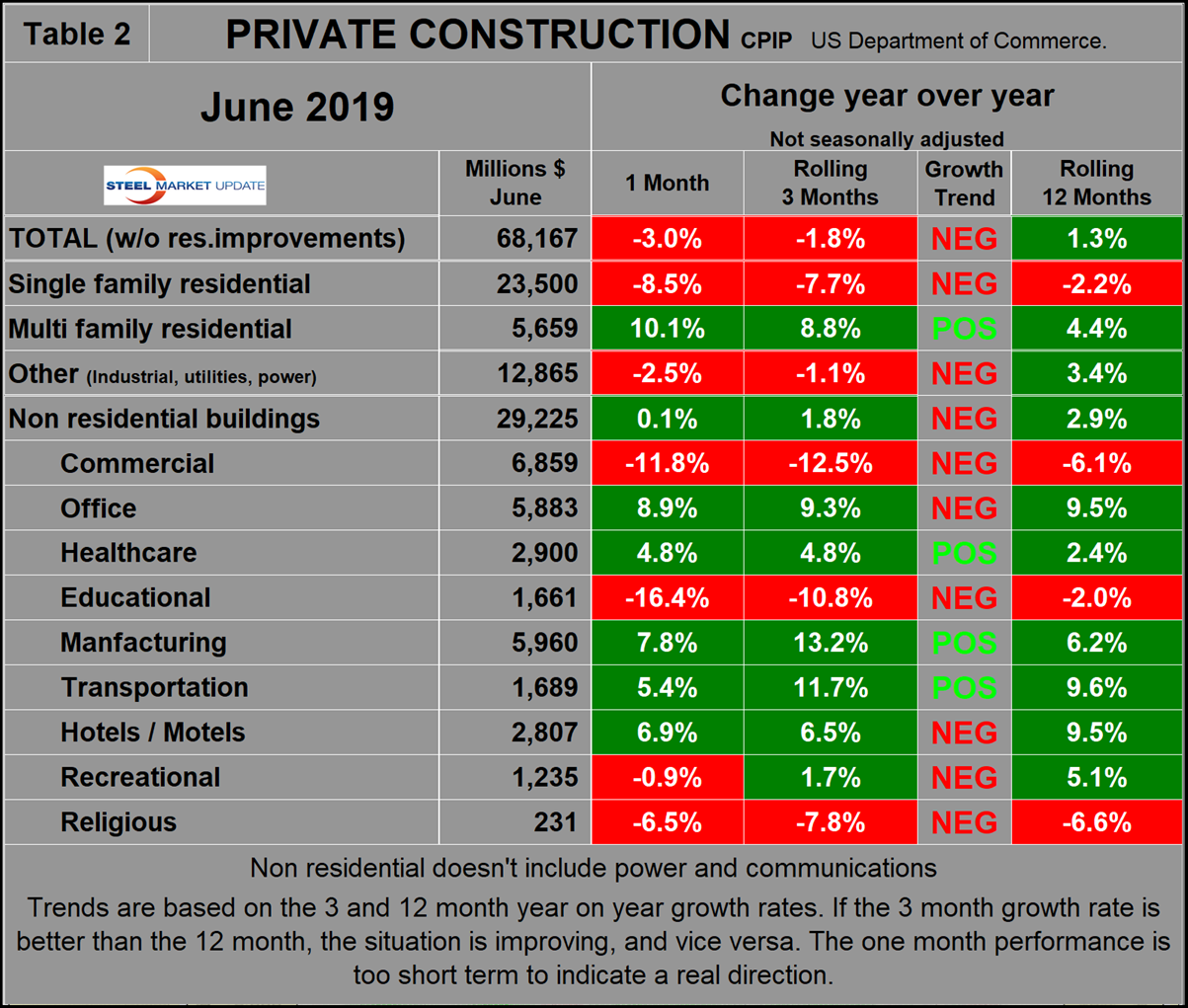

Private Construction

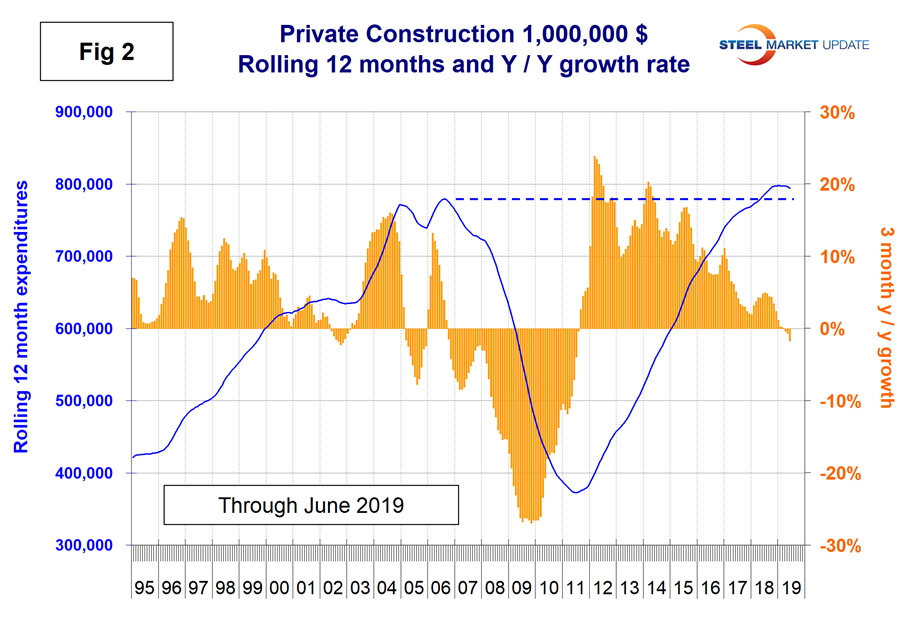

Table 2 shows the breakdown of private expenditures into residential and nonresidential and subsectors of both. The growth rate of private construction in three months through June 2019 was negative 1.8 percent, down from positive 4.8 percent in three months through June last year. Growth has declined continuously in every one of those months as shown by the brown bars in Figure 2. April, May and June were the first months for private construction to experience negative growth since July 2011.

Within the nine sectors of private nonresidential buildings, momentum was mixed with three positive sectors and six negative.

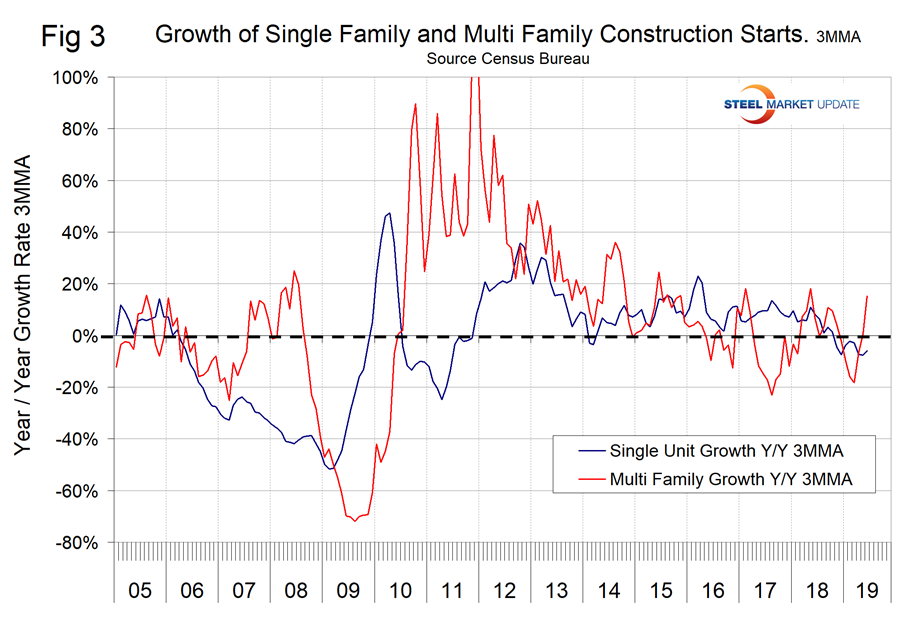

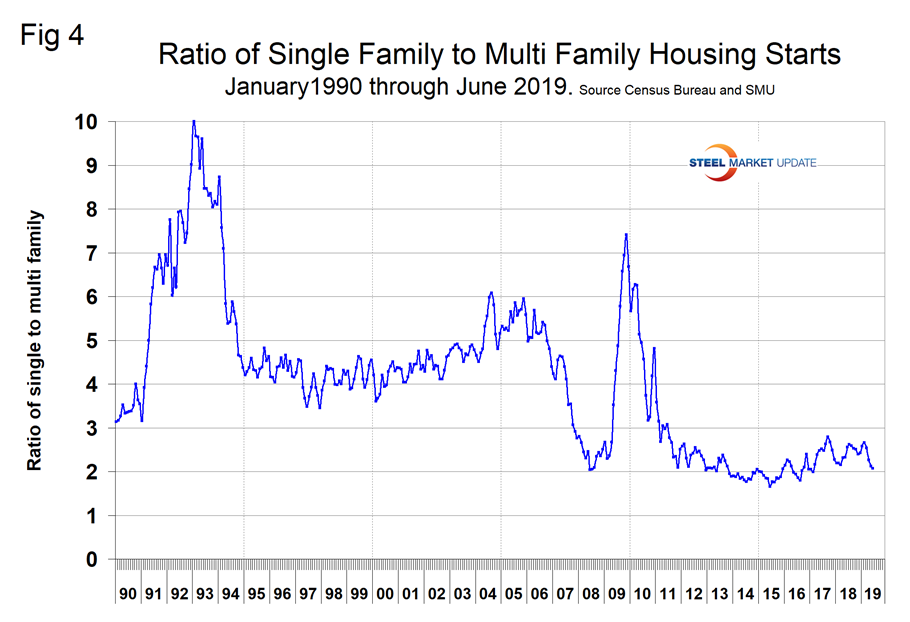

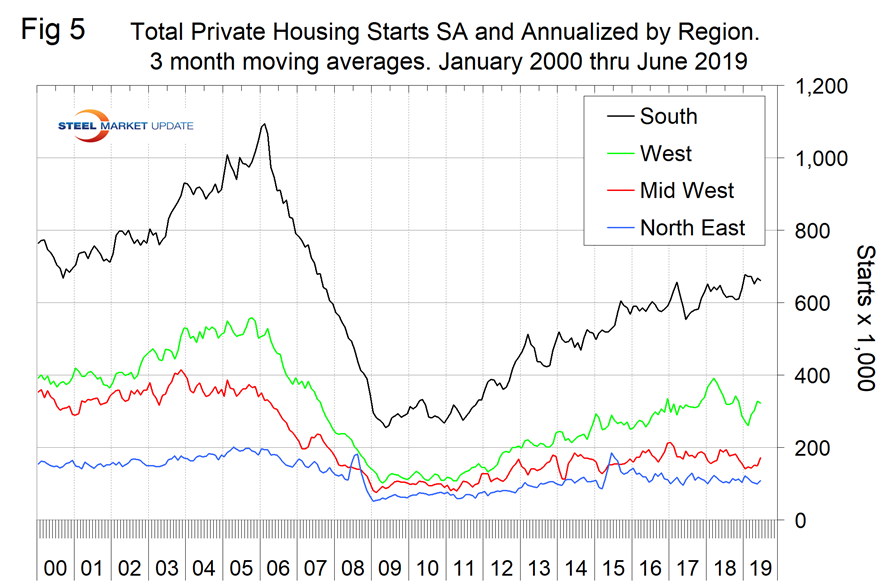

Excluding property improvements, single-family residential contracted by 7.7 percent in three months through June with negative momentum and multifamily residential grew by 8.8 percent with positive momentum. Total housing starts, as reported by Census Bureau, have been contracting on a year-over-year basis since October last year. The National Association of Home Builders optimism index improved in each of the months January through May this year and was stable in June and July, which conflicts with the negative data for CPIP and starts. The Census Bureau reports on construction starts in its housing analysis. In the starts data, the whole project is entered into the database when ground is broken. Construction put in place is based on spending work as it proceeds; the value of a project is spread out from the project’s start to its completion. Single-family starts declined by 6.0 percent in the three months through June year over year, which was about the same as the contraction rate of CPIP. Multifamily starts expanded by 15.2 percent, which was better than the rate of expansion indicated by the CPIP data. Figure 3 shows the growth of both housing sectors since January 2005 and Figure 4 shows the ratio of single-family to multifamily starts. The proportion of single-family gradually increased from January 2015 when the ratio was 1.66 in favor of single units to 2.66 in February before declining to 2.07 in June 2019. Figure 5 shows total housing starts in four regions with the South being the strongest and the Northeast the weakest.

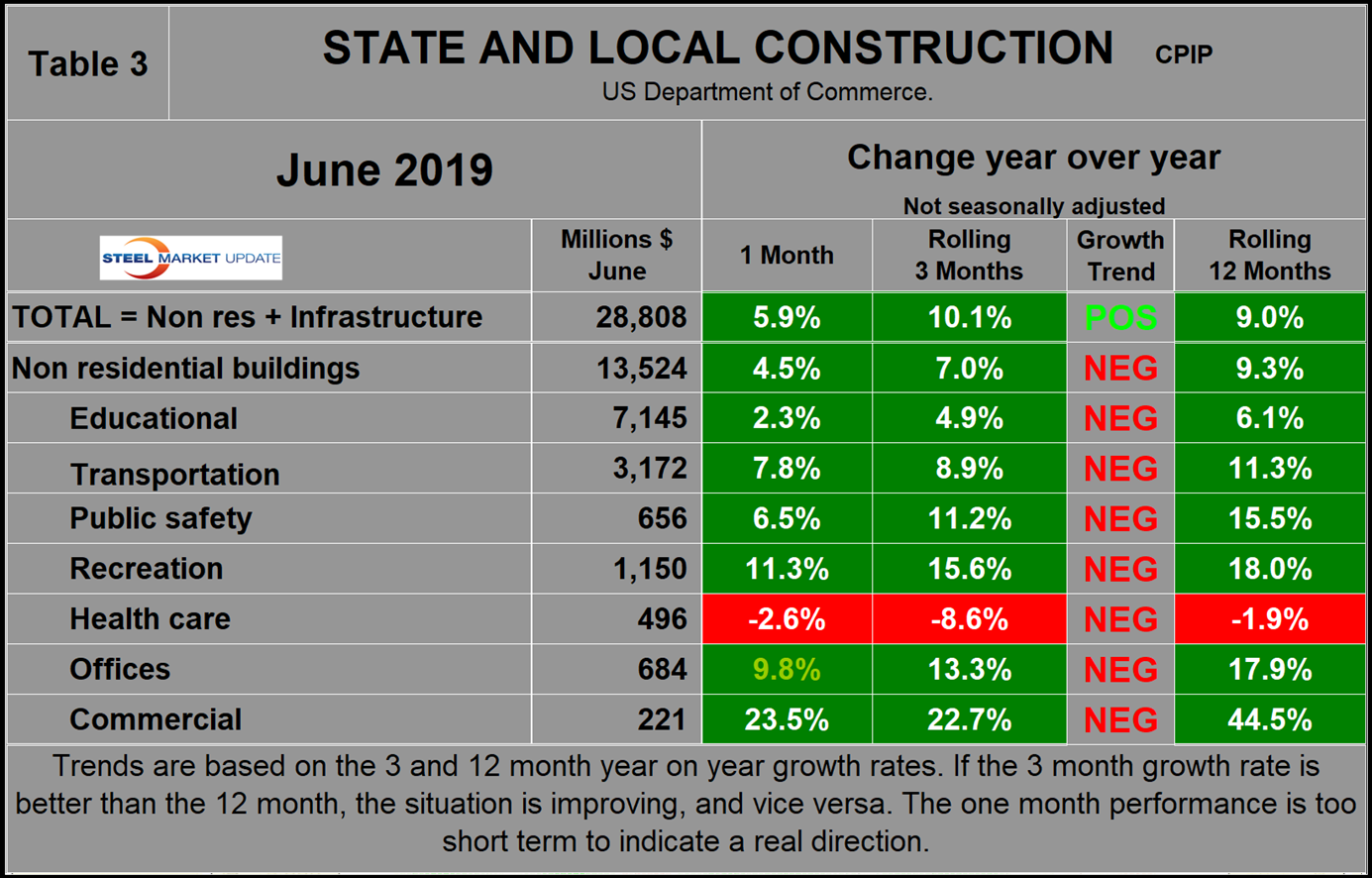

State and Local Construction

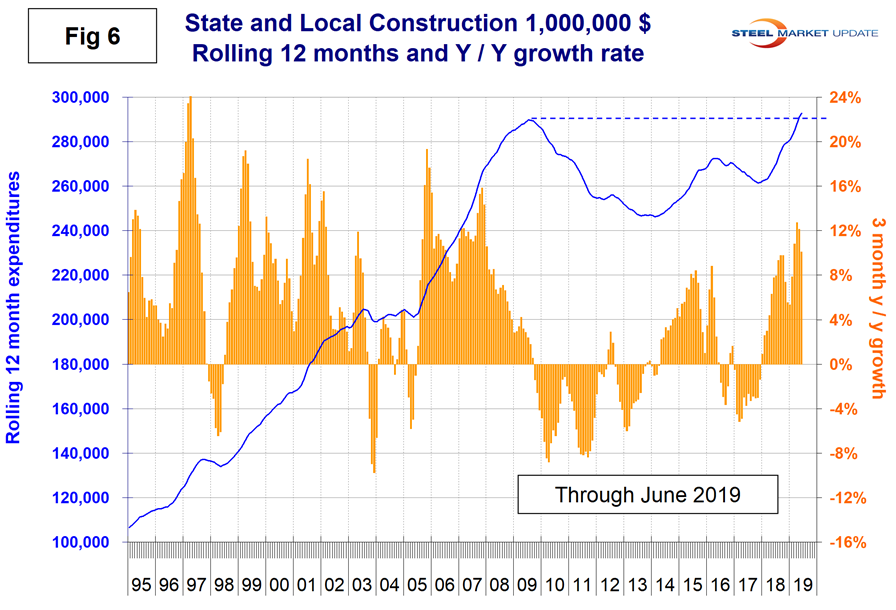

The growth rate of S&L work was in double digits from February through May this year before declining to 5.9 percent in June (Table 3). This includes both infrastructure and nonresidential buildings. S&L nonresidential buildings had slightly negative momentum in June, but still grew at 7.0 percent year over year. Educational is by far the largest subsector of S&L nonresidential buildings at $7.1 billion in June and experienced a 4.9 percent positive growth on a rolling three months basis with negative momentum. Figure 6 shows the history of total S&L expenditures. There has been an abrupt turnaround since the end of 2017.

Drilling down into the private and S&L sectors as presented in Tables 2 and 3 shows which project types should be targeted for steel sales and which should be avoided. There are also regional differences to be considered, data for which is not available from the Commerce Department.

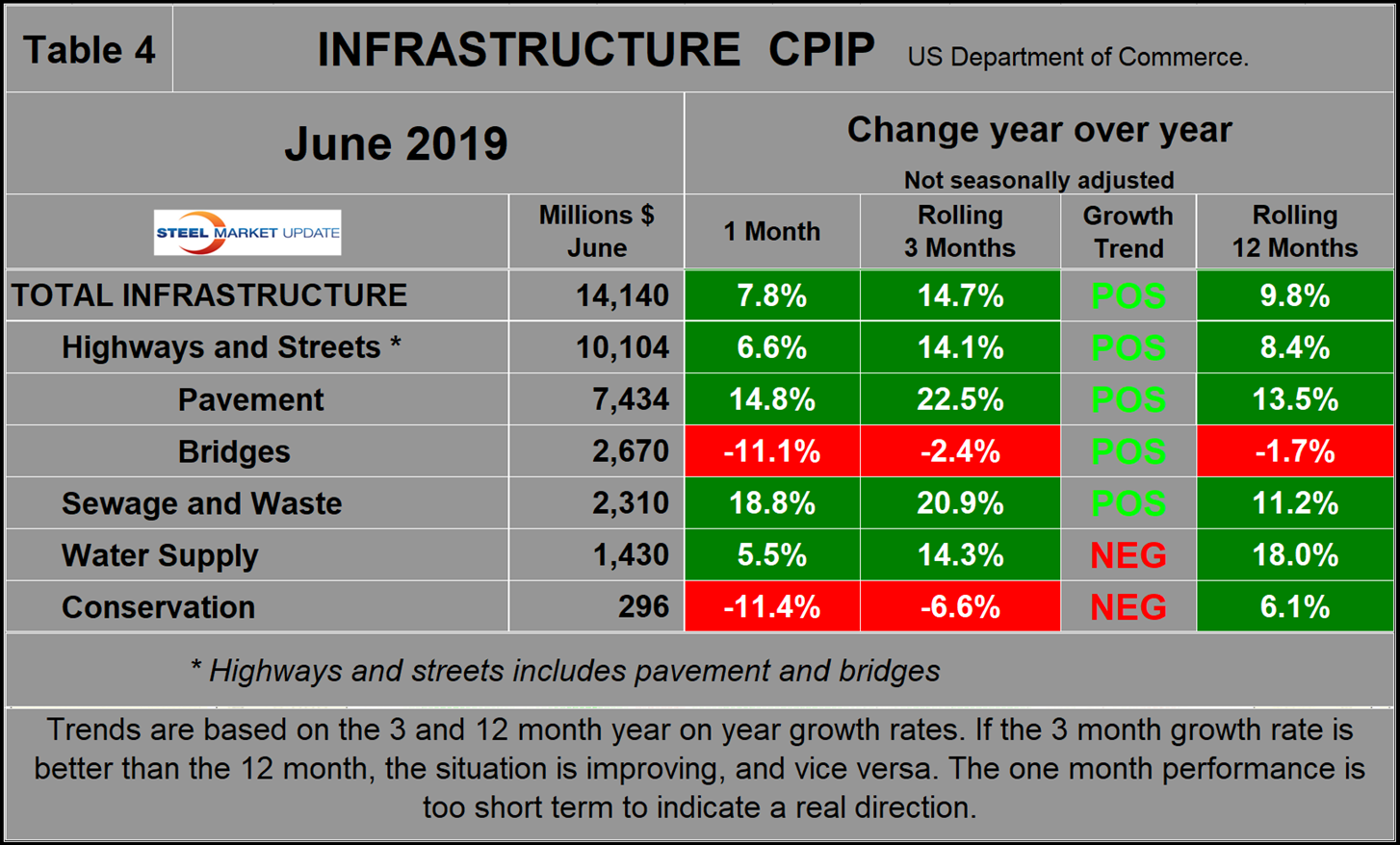

Infrastructure

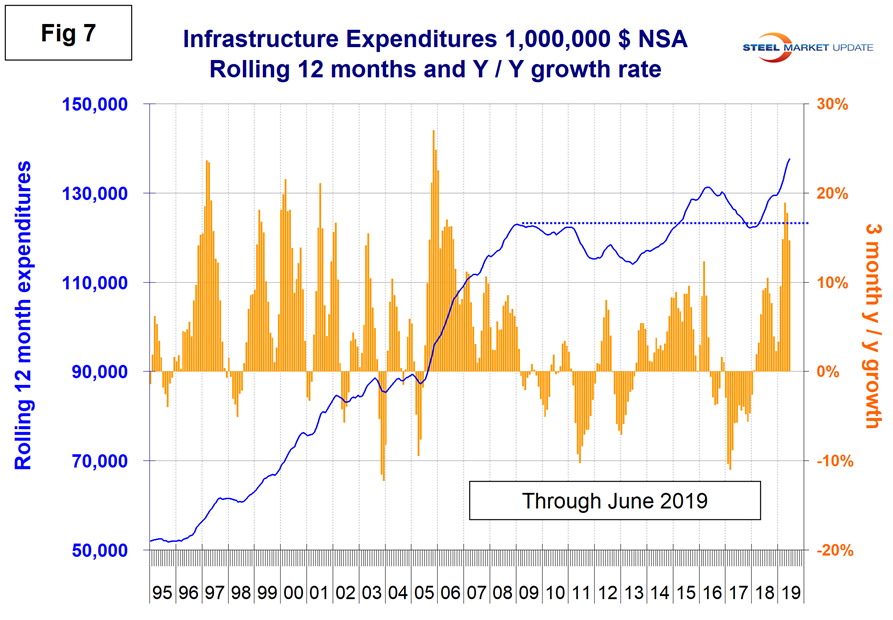

Infrastructure expenditures have had very robust growth in 2019. Year over year, the growth of infrastructure expenditures in three months through June was 14.7 percent with double-digit expansion in each of the last four months of data. On a rolling 12 months basis, infrastructure expenditures in June were at an all-time high. (Note: This is not seasonal as we are considering year over year data.) Highways and streets including pavement and bridges account for about two-thirds of total infrastructure expenditures. Highway pavement is the main subcomponent of highways and streets and had a 22.5 percent growth in three months through June. Bridge expenditures had negative growth in September through January, improved to positive 8.3 percent in March before declining to negative 2.4 percent in this latest data for June (Table 4).

Figure 7 shows the history of infrastructure expenditures and the year-over-year growth rate.

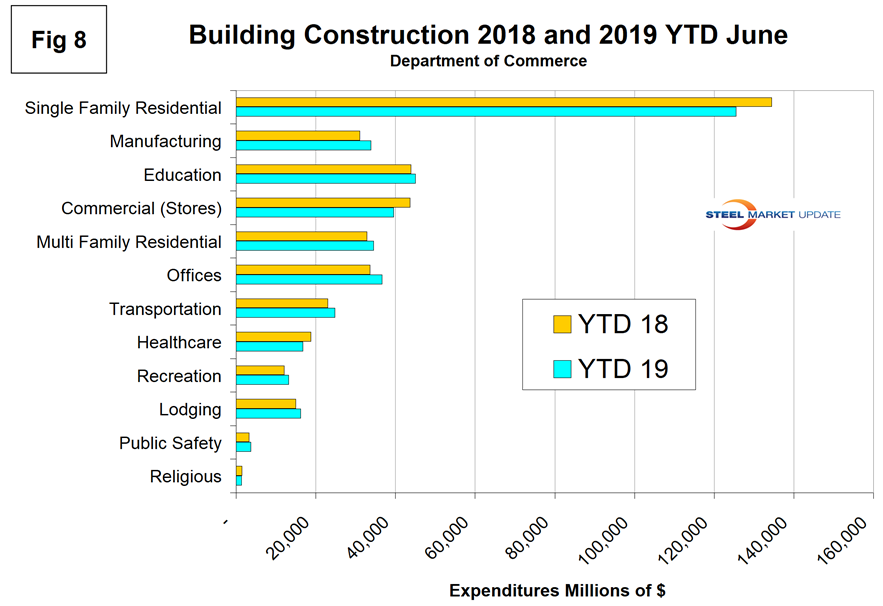

Total Building Construction Including Residential

Figure 8 compares year-to-date expenditures for the construction of the various building sectors for 2018 and 2019. Single-family residential is dominant and in the 12 months of 2018 totaled $281.8 billion. In the first six months of 2019, the annual rate of expenditures was $250.9 billion.

Figure 9 shows total expenditures and growth of nonresidential building construction. On a rolling 12 months basis, expenditures on nonresidential buildings including both private and S&L are at an all-time high and growth has been in the 5 percent range for a year and a half.

Explanation: Each month, the Commerce Department issues its Construction Put In Place (CPIP) data, usually on the first working day covering activity one month and one day earlier. There are three major categories based on funding source: private, state and local, and federal. Within these three groups are about 120 subcategories of construction projects. At SMU, we slice and dice the expenditures from the three funding categories to provide as concise a summary as possible of steel consuming sectors. For example, we combine all three to reach a total of nonresidential building expenditures. CPIP is based on spending work as it occurs and is estimated each month from a sample of projects. In effect, the value of a project is spread out from the project’s start to its completion. This is different from the starts data published by the Census Bureau for residential construction, by Dodge Data & Analytics and by Reed Construction for nonresidential construction, and by Industrial Information Resources for industrial construction. In the case of starts data, the whole project is entered into the database when ground is broken. The result is that the starts data can be very spiky, which is not the case with CPIP.

The official CPIP press release gives no appreciation of trends on a historical basis and merely compares the current month with the previous one on a seasonally adjusted basis. The background data is provided as both seasonally adjusted and non-adjusted. The detail is hidden in the published tables, which SMU tracks and dissects to provide a long-term perspective. Our intent is to provide a route map for those subscribers who are dependent on this industry to “follow the money.” This is a very broad and complex subject, therefore to make this monthly write-up more comprehensible, we are keeping the information format as consistent as possible. In our opinion, the absolute value of the dollar expenditures presented are of little interest. What we are after is the magnitude of growth or contraction of the various sectors. In the SMU analysis, we consider only the non-seasonally adjusted data. We eliminate seasonal effects by comparing rolling three-month expenditures year over year. CPIP data also includes the category of residential improvements, which we have removed from our analysis because such expenditures are minor consumers of steel.

In the four tables included in this analysis, we present the non-seasonally adjusted expenditures for the most recent data release. Growth rates presented are all year over year and are the rate for the single month’s result, the rolling three months and the rolling 12 months. We ignore the single month year-over-year result in our write-ups because these numbers are preliminary and can contain too much noise. The growth trend columns indicate momentum. If the rolling three-month growth rate is stronger than the rolling 12 months, we define that as positive momentum, and vice versa. In the text, when we refer to growth rate, we are describing the rolling three-month year-over-year rate. In Figures 1, 2, 6, 7 and 9 the blue lines represent the rolling 12-month expenditures and the brown bars represent the rolling three-month year-over-year growth rates.