Prices

June 13, 2019

CRU: Mines and Projects at Risk from Lower Prices

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU Senior Analyst Christine Meilton

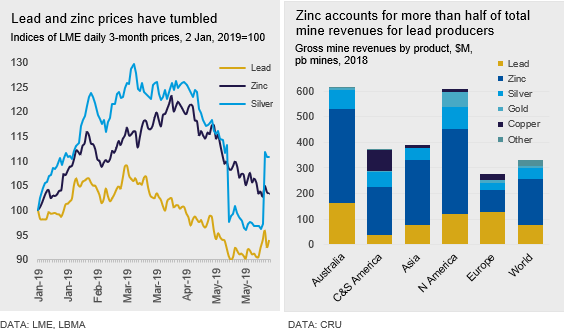

This month we’re looking at mine profitability and the tonnage at risk from lower metals prices and higher treatment charges, both for operating mines and new projects. Recent weeks have seen both zinc and lead prices tumble, and CRU believes that both metals have now passed a cyclical peak and will track lower over the medium-term. After peaking in mid-April at $3,000/t, zinc prices have lost more than 10 percent to trade around $2,600s/t, although they are still higher than at the start of this year. However, with demand still weak and production on the rise, they are only expected to trend further down. Sister mining metal lead peaked earlier, in February of this year, and although it has picked up in recent days on news of the outage at Port Pirie, it is not expected to make significant further gains. Indeed, after a seasonal recovery in the second half of this year it, too, is expected to track lower as the market moves into a surplus.

As zinc prices once more approach the level at which mine cutbacks and closures have occurred in the past, we have looked at the tonnage that is at risk from lower prices, particularly in a context of higher TCs. Furthermore, with mine supply growth for both zinc and lead beyond 2020 dependent on the development of as yet uncommitted projects, we look at the impact of lower prices on project approvals.

Our analysis is from the point of view of zinc mines and costs, but we also consider the impact of zinc cutbacks and closures on lead mine production. Much of lead mine output is as a by-product, or at best a co-product, of zinc and thus largely dependent on developments in the zinc market. While decisions are unlikely to be taken on the basis of zinc alone, it is the more dominant factor. As the right-hand chart below shows, zinc accounts for, on average, more than half of total mine revenues for lead mines, with lead accounting for only around 20 percent. This is partly geology and partly price. Many mines are zinc rich and lead poor, and are becoming increasingly so, with zinc ore grades typically 1.5 to 2 times those of lead ore grades. Moreover, zinc is the more valuable metal, and so revenues will inevitably be higher except in the case of the few main lead product mines, such as Doe Run’s Missouri mines.

Lower Prices Will Put Mines at Risk of Closure While Stifling Project Development

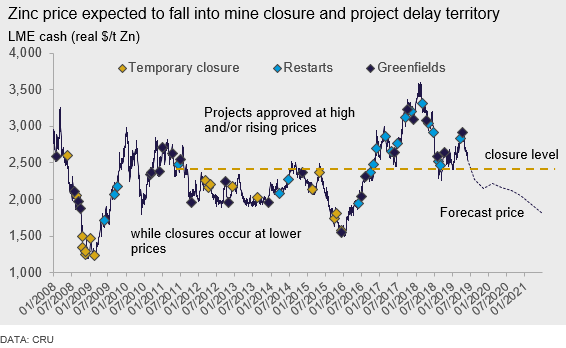

Before looking at mine cutbacks in more detail, we have done some recent historical analysis on the impact of the price environment on mine production decisions. The chart below indicates the prices at which closures have occurred and those at which project approvals have been given over the last 10 years.

While there will always be exceptions, it can be clearly seen that project approvals mostly occur at high and/or rising prices. This is particularly true of mine restarts; many of these mines were initially closed due to low prices and are thus price sensitive. The floor for project approvals is around the $2,000/t level, below which we would not expect to see projects given the green light, and in a falling price environment approvals will dry up at higher levels than this. The recent price rally saw a number of restarts approved and coming back on stream, including some which had previously closed due to low prices and are now again on the margins of profitability, for example Nyrstar’s Tennessee mines and Campo Morado in Mexico. Under our bearish price outlook for the next few years we would not expect to see many, if any, further approvals, even if the mines would be profitable at the lower prices, as producers will wait for the upturn in prices.

We have identified a total of 24 approvals since the beginning of 2016, of which 10 have been for greenfield projects and 14 for restarts. Ironically, having been approved during the upturn, the latest of these greenfield projects will be coming on stream during the downside of the price cycle. These include Asmara in Eritrea, Votorantim’s Aripuana in Brazil and Peñoles’ Juanicipio in Mexico, the latter having only been approved during the first quarter of this year. However, it is also a major gold and silver producer and so zinc prices are less significant for this operation. Asmara will also produce copper, silver and gold. Indeed, initial production will be of supergene and gold ore, and zinc production will not begin until the fourth year of operation when mining of the underlying primary ore begins.

We have also identified the price level at which closures begin to happen, which historically has been at around the $2,400/t level. However, closures do not occur straight away. In the 2008-09 slump, with the exception of one early closure, zinc prices had been declining for over six months before a flurry of closures occurred in the final few months of the year. Similarly, in 2011-12, although the price turned in mid-2011, slipping below $2,400/t in August, it wasn’t until March of 2012 that the first closures started to occur. Moreover, mines held out for longer during this period, perhaps because the price decline was less severe, and the final closures (Glencore’s mines) did not occur until the final quarter of 2015. However, it should be remembered that these mines were not actually loss making at the time, but the closures were for strategic reasons and were seen as an attempt (which was successful) to turn the market around. The final economic closure (Myra Falls) was in April 2015.

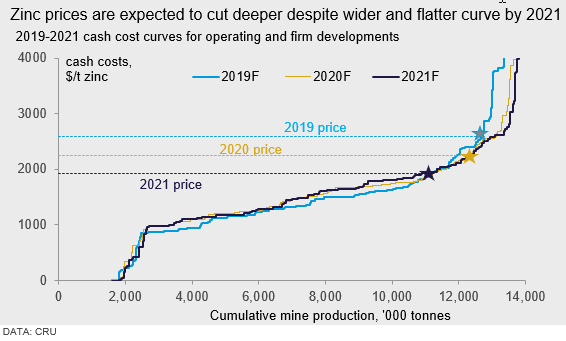

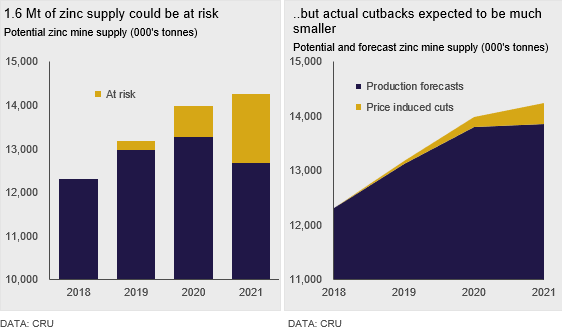

Lower Prices Will Put 1.6Mt of Zinc and 500kt of Lead Mine Production at Risk

Three-month zinc prices are now approaching the $2,400/t level and CRU’s forecast sees them dropping through and remaining below that level for the next two years and beyond. While we see the bottom of the price cycle occurring in mid-2021, we expect only a fairly gradual recovery thereafter. Meanwhile, cost inflation is expected to be a key feature of the zinc market over the next few years, as the U.S. dollar begins to normalize (and weaken), energy and consumable price inflation begins to pick up, and treatment charges continue to rise as a result of growing concentrate surpluses. Thus, at the same time as prices are expected to fall, the cost curve will rise, and prices will cut deeper into the curve by 2021.

However, one thing we can learn from the historical analysis above is that miners will continue to operate for many months at low or negative profitability before a closure (or mine plan adjustment i.e. raising cut-off grades) decision is taken. Thus, over the forecast horizon considered here, the risk of mine closures increases as low prices persist for longer, but we also believe that 2021 will be the peak year for closures.

Using CRU’s mine cost model, we have identified those mines for which the forecast price will be below cash costs, net of by-products, under CRU’s forecast prices for zinc, lead, silver, gold and copper. We are also forecasting lower prices for lead, alongside zinc, which has the effect of lifting the cost curve for zinc, although for a handful of mines this will be offset by the impact of relatively higher copper prices.

By 2020, we calculate that 1.8Mt, 13 percent, of potential zinc mine production at operating mines and committed projects, will be losing money, and by 2021 this rises to more than 3Mt, or nearly 25 percent as prices cut deeper into the cost curve, breaching the 80 percent percentile. Based on the historical analysis above we assume that none of these operations will close (or cut back) straight away but will continue to burn cash for several months. Producers may also be able to temporarily high grade or adjust their mine plans, defer spending or have price hedges in place. Taking all these factors into account, we assess the total tonnage at risk to be 0.7Mt in 2020 and 1.6Mt by 2021. However, our final production forecasts assume much more modest losses, 180,000t in 2020 rising to 400,000t by 2021, again based on the empirical analysis and actual losses seen in past periods of low prices.

Mines at the top end of the cost curve and at risk include those that have closed under previous periods of high prices: Nyrstar’s Tennessee mines (which closed in 2008-09 and again in 2015), Langlois (closed in 2008-09), Campo Morado (closed in 2015), CBH Resources’ Endeavor (cut back 2015), as well as small mines in South and Central America and China.

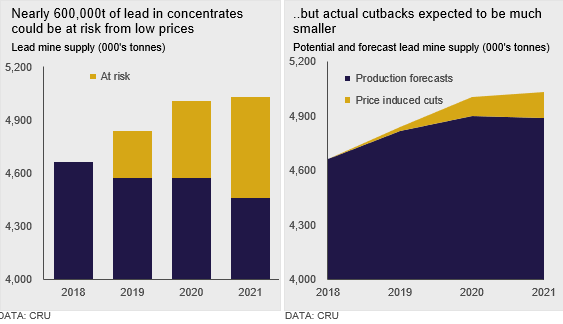

On the lead side, we have considered the lead production at those mines considered to be at risk from low zinc prices as well as any at-risk main product lead mines. By 2020, 0.5Mt or 11 percent of potential production will be losing money, rising to 1.1Mt (21 percent) in 2021. Using the same assumptions as above, we assess the tonnage at risk to be 0.4Mt in 2020 and 0.5Mt in 2021, almost all of which is as a by- or co-product with zinc. The only loss-making non-zinc producing mines are very small operations at which lead is a by-product. The final production losses used in our forecasts are 100,000t in 2020 and 145,000t in 2021.

Most Projects Will be Profitable at Forecast Prices

While we think it is unlikely that we will see any project approvals for the next couple of years, it is nevertheless interesting to consider the cost position of the portfolio of projects in our probable and possible categories, as this may indicate when the projects may be approved. Of our project portfolio, more than 90 percent of the potential production will be covering costs at our forecast prices, with just two potential zinc/lead mines and one lead mine not covering costs. This suggests that once prices are firmly back on an upward path, we should see project approvals starting to be made, subject to the necessary studies being completed, permits being received and financing being raised. Of course, the latter will depend on the project’s economics together with the prevailing price environment, both of which will be positive.