Overseas

April 7, 2019

CRU: Chinese VAT Reduction on Steel – Friend or Foe?

Written by Tim Triplett

By CRU China Analysts

China released a slew of stimulus measures during the NPC and CPPCC meeting in March in order to avoid a material slowdown in economic growth in the short term. Further and more substantial cuts to VAT rates were one of those measures. This followed an earlier VAT reduction from 17 percent to 16 percent for manufacturing industries in May 2018, partly to tackle the downside risks to growth from U.S.-China trade tensions emerging at that time.

While VAT has become one of China’s most important taxes and accounted for 39 percent of the entire Chinese tax take in 2017, the most recent cut underlines the focus on tax cuts rather than government spending to stimulate growth in the current stimulus round. It is also consistent with the overarching goal to transition the economy to a more balanced growth model – away from investment-led and toward consumption-led growth. We detail the most recent round of stimulus efforts, and compare with previous stimulus episodes, in our recent “China Stimulus 2018-19: Less is Not More” Special Feature.

Key findings:

• Domestic end consumers of goods made from steel stand to see prices fall, to their benefit, because we expect most of the VAT savings to be passed right through the value chain given current market conditions. This may encourage additional consumption of manufactured products, which is an intended outcome of the latest round of economic stimulus.

• All domestic supply chain participants then stand to benefit from greater demand for their products, output, improved capacity utilization and therefore profitability.

• There is a small theoretical direct uplift in margin available to supply chain participants stemming from the reduction in tax on their value added. However, this may also be passed along the supply chain in the form of lower prices.

• Some traders have sought a one-off win by claiming VAT refunds on input costs at 16 percent on purchases of raw materials made before April 1, and a lower VAT rate on sales of 13 percent by withholding such sales until after this date. This caused a one-off perturbation in the supply-demand balance, which boosted prices in late March as supply from stockholders was artificially limited, and their purchases from mills accelerated.

• Overseas buyers of Chinese steel stand to benefit from lower prices of up to 3 percent or around $15 /t. This should help Chinese export competitiveness against marginal suppliers to South East Asia, but is not transformative and will not result in a surge of exports.

Impact on Steel Market

We judge the outcomes of the change in VAT rates to be as follows:

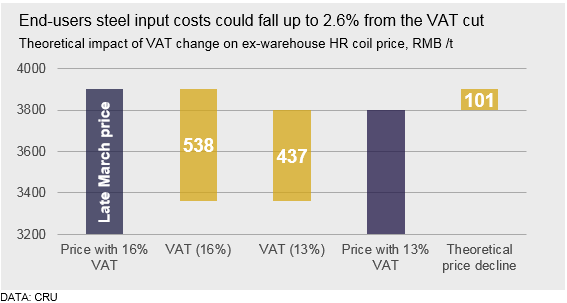

Domestic prices fall: A reduction in VAT rates means that domestic steel prices can be lower than they would otherwise have been if ignoring any other effects (see later), because the saving in tax, which would have been paid to the government, can be passed on to the customer. This is broadly the expectation in the steel supply chain given the market remains highly competitive and fragmented.

The price of steel is therefore reduced by up to the full extent of the change in VAT to the next firm in the supply chain. This is illustrated in the example case of a Chinese domestic stockholder chart below, but equally applies for a mill-direct sale to an end-user, or mill to stockholder sale. In this case, using end-March ex-warehouse prices, the maximum theoretical price reduction that could be attributed to the VAT change in isolation is around 2.6 percent or RMB100 /t ($15 /t), assuming that the stockholder passes on the full saving to their customers.

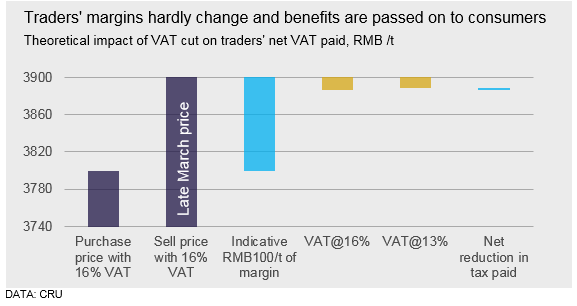

Margins may rise for supply chain participants: VAT is based on the increase in value of a product or service at each stage of production or distribution. There can therefore be a small uplift in margin available to a supply chain participant, which stems from the fact that VAT can be reclaimed on certain input costs. In our stockholder example:

• VAT on input costs (i.e. purchased steel from mills) can be claimed back. This claim was reduced from 16 percent to 13 percent of eligible input costs;

• The stockholder pays less VAT on its sales, 13 percent not 16 percent;

• Steel purchase costs are lower than selling prices (by approximately the amount of margin the stockholder makes on each tonne sold);

• 3 percentage points (the difference between 16 percent and 13 percent) on VAT claimed back on input costs is less than 3 percentage points saved on selling prices because the former is a smaller number (by the amount of the margin);

• Therefore, a net gain is realized equal to around 3 percent of the margin i.e. the value-added. This example is an approximation given VAT does not apply to all costs (e.g. does not apply to labor).

This effect is illustrated below. The stockholder, in this example, may then choose to retain that small additional margin or pass to customers in the form of marginally lower prices (above and beyond the direct impact of the cut in VAT on sales). Either way the impact is very small for a stockholder or trader, but may be larger for other supply chain participants where a greater proportion of input costs are not VAT-deductible and/or margins are very high.

One-off win for some traders and stockholders: Some stockholders and traders have sought to benefit from this mechanism by withholding sales of material purchased before April 1 until April or later. This allows for reclamation of VAT on input materials at the 16 percent rate, but payment of VAT at only 13 percent on their sales, effectively boosting margins. This, where seen, created short-term ex-warehouse price support due to artificially-limited supply and some volatility in the second half of March.

At the same time, traders were keen to buy from mills in order to qualify for the 16 percent VAT deductibles on material they knew could be sold attracting the new 13 percent VAT rate. And so steel mills started to increase their offer prices by RMB20-30 /t as their orderbooks strengthened. In other words, the VAT change caused a short-term perturbation in the supply/demand balance, which had the effect of applying upward pressure to prices.

This is obviously a one-off effect, but we believe has been exploited to some extent. It is limited as this tactic requires an increase in working capital and raises price risk. This case, where deployed, is illustrated below.

Why have domestic prices risen in reality? While the VAT cut implies prices are lower than they would otherwise have been, ex-warehouse prices increased in the first week of April – why? Firstly, underlying demand has improved, including in the infrastructure sector and with some seasonal demand improvement in construction activity. This has, in turn, meant inventories are lower. Sentiment has also been buoyed by the cut in VAT, with the promise (see below) but not yet reality of improved demand from machinery, transport and other mainly flat product-consuming sectors. At the same time, some mills are still undertaking maintenance in April, a view confirmed recently by CRU analysts who were present at CISA’s 17th International Steel Market and Trade Conference in Nanjing.

Modest demand improvement for all supply chain participants: In a competitive market such as steel, VAT savings are likely to be passed through the supply chain with little or no margin benefit to upstream and mid-stream firms. This means the majority of price benefit will wash right through the value chain to the end-consumer i.e. a purchaser of a washing machine, car or other good manufactured with steel.

This may encourage greater consumption of such goods than would have otherwise been the case, and is therefore the mechanism by which demand for the manufactured good and all upstream intermediate products, including steel, is intended to be stimulated. CRU will write more on this in the coming month, though this effect is already incorporated into our base case steel demand forecasts.

Export prices will fall, at least at first: Like domestic prices, the cut in VAT means that Chinese export prices will be lower than they would otherwise have been for the majority of steel products. The mechanism by which export prices are lowered and demand for Chinese-origin steel stimulated is the same as described above. However, there is an additional variable: the VAT rebate.

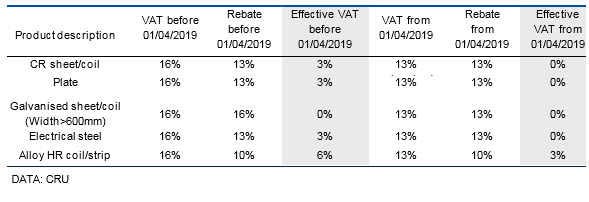

What is the VAT rebate and is it changing? VAT is levied on both domestic and, unusually compared with most countries, export sales. However, rebates of varying amounts can be applied to VAT on exports. The rebate is effectively money that can be claimed back from the government to offset a VAT charge. This means that there is an effective VAT rate equal to the gross VAT rate less the rebate.

Changes in the rebate have been used to manage exports of steel: in general, to encourage exports of high value-added products and to control those of low value-added and sensitive commodities i.e. those which consume much recourse to produce but are of low value, or where there is a judgement that avoiding trade tensions in specific product areas is desirable. For example, HDG coil, a more value-added product, has enjoyed a full rebate, whereas that on HR coil has been 0 percent (and an export tax applies to certain even less value-added semi-finished products).

Changes to VAT and VAT rebates for selected products are summarized in the table below:

VAT rebates on export sales have remained unchanged for most products, meaning that the VAT reductions translate directly to a reduction in the effective VAT rebate (i.e. VAT less any rebate) and therefore have the potential to make export prices lower than they otherwise would have been, by the amount of change in effective VAT – around 3 percent.

Wide HDG coil is an exception, as there was formerly a full (16 percent) rebate, and this is still the case (a full 13 percent rebate), meaning the effective VAT of 0 percent remains unchanged. Therefore, HDG coil export prices would not, in theory, change due to the VAT rate change.

Overall, the implication is that export prices, with the exception of cases such as HDG coil, will be around 3 percent lower than they would have otherwise been had there been no change in VAT rates. This equates to around $15-17 t/ depending on the product i.e. most Chinese steel exports gain in price competitiveness by up to this amount. Current market conditions are such that it is likely that exporters will choose to pass on most of the VAT saving to their overseas customers, rather than improve their margins. Price-sensitive buyers in Southeast Asian markets have seen that VAT rates on exports have fallen, and are therefore asking for lower prices from their Chinese suppliers as a result.

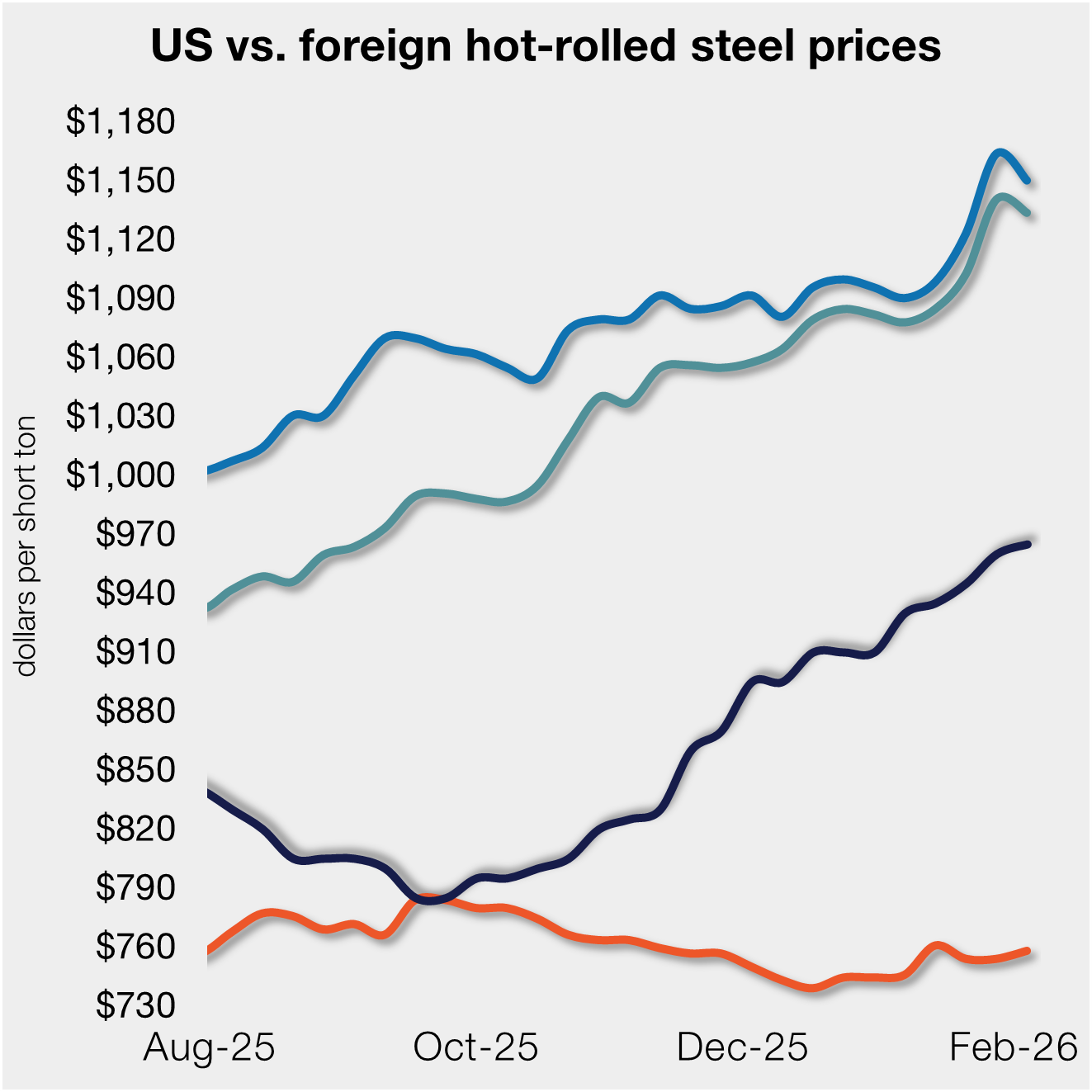

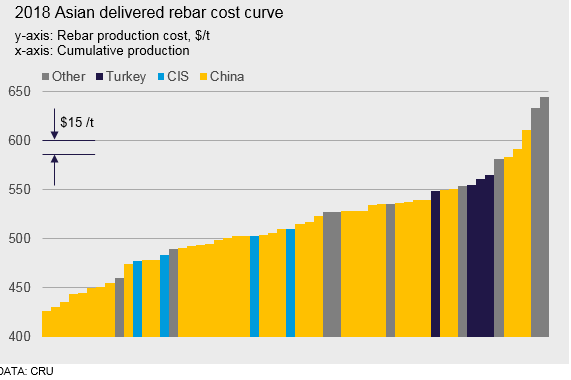

Does this give China a competitiveness boost? Yes, by up to $15 /t. However, this is not transformative in the sense that this would bring a large incremental volume of new competitive Chinese supply to the market, and the delivered Southeast Asia cost gap with other potential suppliers is much greater – the gap between the highest cost Chinese and CIS-origin rebar supply is around $100 /t by comparison as shown in the chart below. On the other hand, marginal supply from Turkey, as was seen in late 2018 and early 2019, can be more easily fended off. Without a commensurate relative fall in scrap vs. hot metal costs, Turkish steel will have a much more difficult or impossible task in penetrating Asian markets, especially in times of Chinese domestic market weakness.

Overall, lower VAT on exports is just one part of the reasoning behind CRU’s forecast of an increase in Chinese net exports of steel in 2019. But it will not in itself facilitate a surge in export volumes. Indeed, the boost, albeit modest, to domestic demand from stimulus measures this year should also help limit the rise in Chinese exports.

However, according to the Chinese tax bureau, further revisions to VAT rebates may be made before June 30, as we are not in the usual window for the government to make such changes. Rebate increases, if seen, have the potential to reduce export prices further.