Market Data

January 14, 2019

SMU Recession Monitor: Markets Becoming More Nervous

Written by Peter Wright

Indicators of economic activity in the U.S. do not predict an imminent recession, but the yield curve and housing permits should be on our radar screen.

Recessions are defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the organization tasked with identifying when a recession starts and ends, as back-to-back quarters of negative economic growth.

This is a report we have been producing every three months. We are now increasing the frequency to monthly as the pundits are discussing the timing of the next recession. Viewed individually, the leading indicators we track offer some insight into future economic expansion or contraction. Viewed collectively, they give subscribers a better idea of present and future business activity. Since World War II, most recessions have been preceded by an overheated economy as indicated by low unemployment, tighter monetary policy and rising long-term interest rates.

![]()

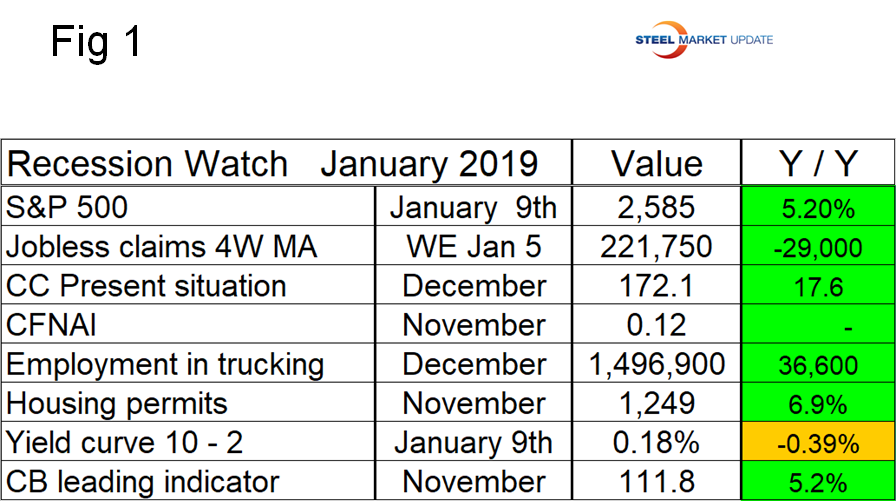

Figure 1 is a heat map of the eight indicators tracked in this analysis. Only the yield curve, which has been a strong predictive indicator in the past, is showing signs of distress.

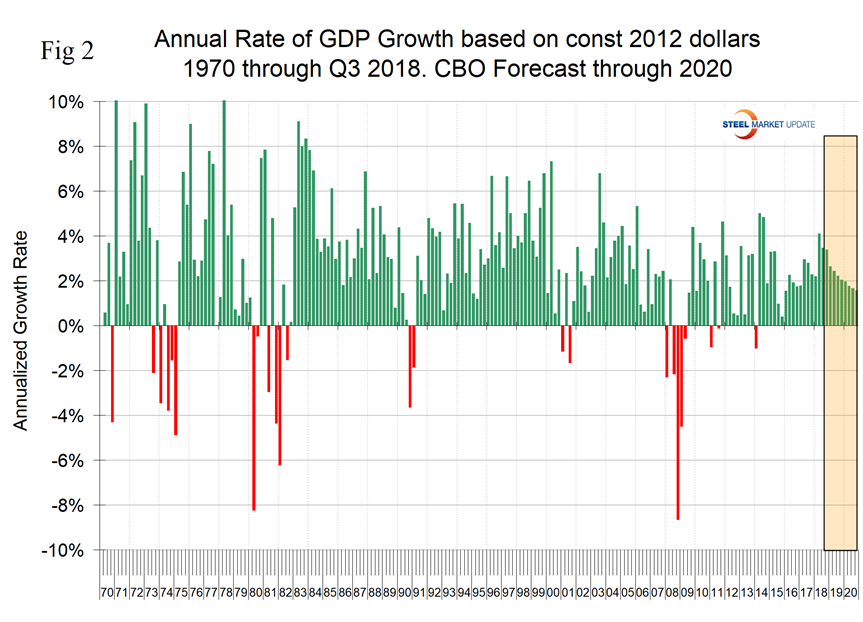

Figure 2 provides a history of U.S. recessions since 1970. Recessions occurred in 1974, 1980, 1981, 1990, 2001 and 2008. In its third estimate of the growth of U.S. GDP for Q3 2018, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported the growth of GDP to be 3.36 percent. This is a quarter-on-quarter result. On a trailing 12-month basis, GDP grew 3.0 percent in Q3. This was the first quarter to reach 3.0 percent on that basis since Q2 2015. Congressional Budget Office economists expect economic growth to decline in upcoming quarters, but not to become negative through 2020.

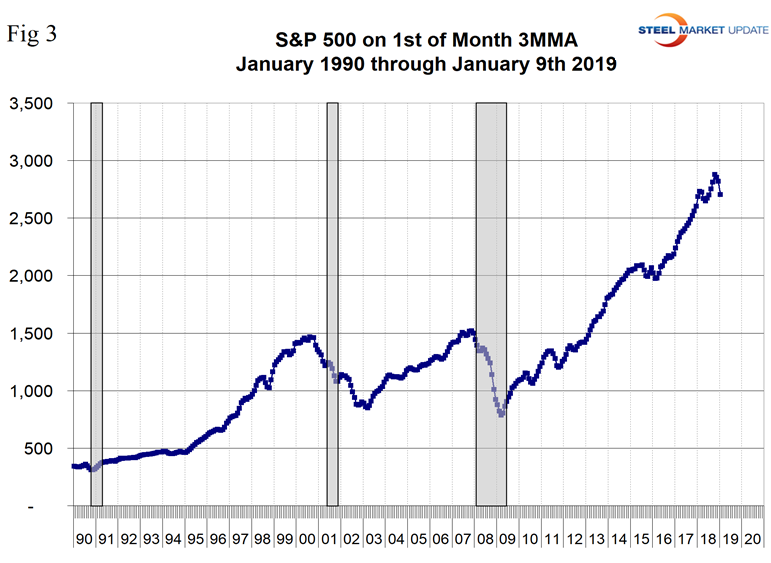

Figure 3 shows the three-month moving average of the S&P 500 at the beginning of each month from January 1990 through January 2019. The stock market did predict the recession of 2001, but failed in 2008. Since then there have been several blips, which proved of little significance. The tendency is that stock prices decline as investors anticipate a weakening economy and flagging corporate earnings. Fed tightening is also a factor in today’s world.

On Dec.17, the Royal Bank of Canada wrote: “The U.S. stock market has been in a correction since early October, joining many of its global peers that had been weak for months before that. The major U.S. averages have given up 12% to 13% from their peak levels so far. There have been bouts of heavy selling followed by rallies, but prices have not yet reached down to levels that have attracted sustained new buying. As investors look to 2019 and beyond, the underpinnings that gave them such confidence—big fiscal spending budgeted for 2018 and 2019, corporate and personal tax cuts, and upbeat management guidance—now have given way to concerns about the impact of Fed tightening on the 2020 economy and earnings. That said, we regard this as a correction and not something more; we think the market advance that began in 2009 has further to run. Our principal reason for holding this view is that the U.S. economic expansion remains in gear, as do those of most important economies. The overt tightening of credit conditions and deterioration in the labor market that would tell you a recession is on the way are not yet in evidence.”

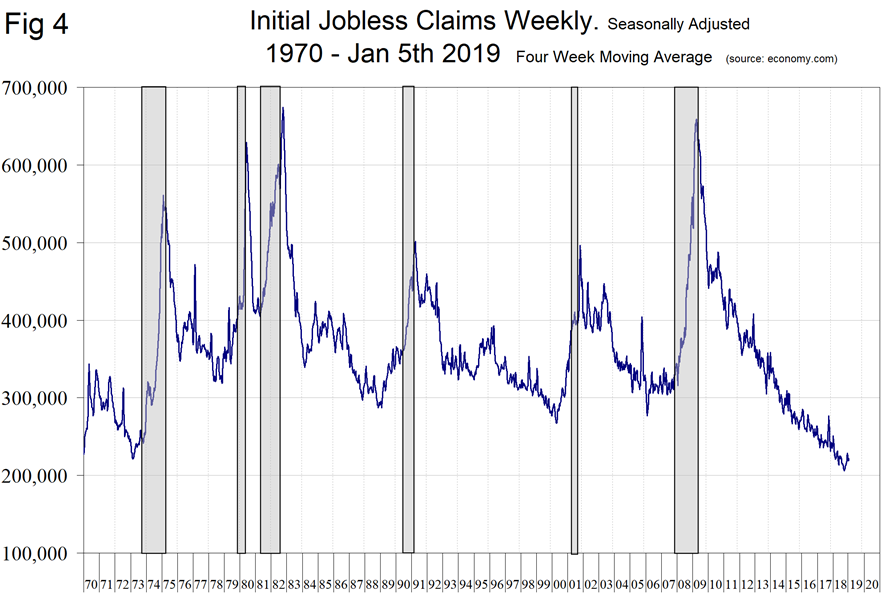

Figure 4 records new weekly claims for unemployment compensation. This indicator failed to predict the 1981 and 2008 recessions. It had a lead of over a year on the other four. Initial claims for unemployment insurance, reported weekly, are a sensitive measure of layoffs. Initial claims are currently at a 50-year low.

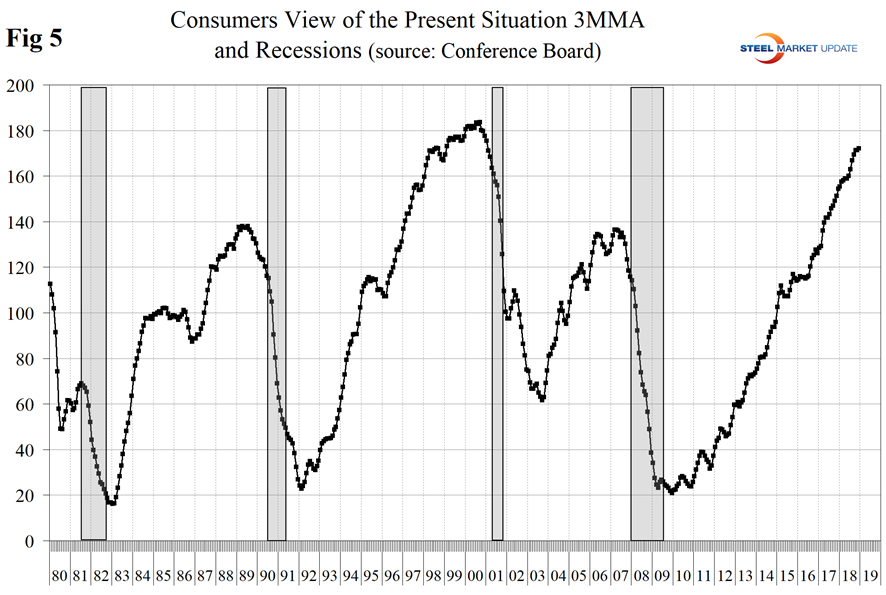

Consumer Confidence: When consumers, businesses and investors lose confidence, it sets up a downward self-reinforcing spiral of reduced spending and investment, causing even higher unemployment and further depressing confidence. This month we have taken a closer look at this data stream. Consumer confidence is reported as sentiment indexes of the present situation and as expectations and a composite of the two. It appears that the consumer’s view of the present situation is the best predictor of future recessions and this is shown in Figure 5.

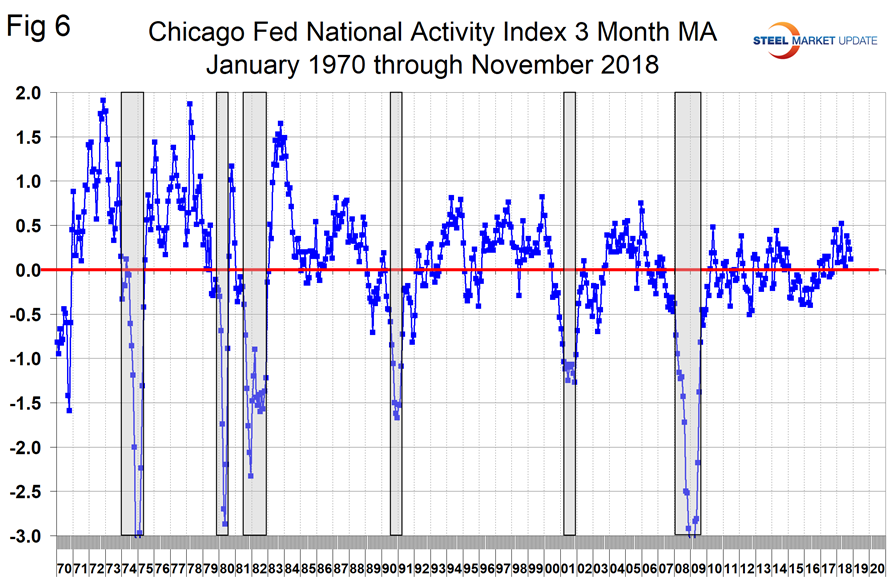

Chicago Fed National Activity Index: “This index is a weighted average of 85 indicators of national economic activity drawn from four broad categories of data: 1) production and income; 2) employment, unemployment and hours; 3) personal consumption and housing; and 4) sales, orders and inventories (Figure 6). A zero value for the index indicates that the national economy is expanding at its historical trend rate of growth; negative values indicate below-average growth; and positive values indicate above-average growth. When the CFNAI-MA3 (three-month moving average) value moves below –0.70 following a period of economic expansion, there is an increasing likelihood that a recession has begun. Conversely, when the CFNAI-MA3 value moves above –0.70 following a period of economic contraction, there is an increasing likelihood that a recession has ended.

Since our data stream began in January 1970, the CFNAI has predicted every recession, but in-between there have been stumbles and false alarms. Figure 1 does not show a year-over-year comparison for the CFNAI because it is not a progressive indicator.

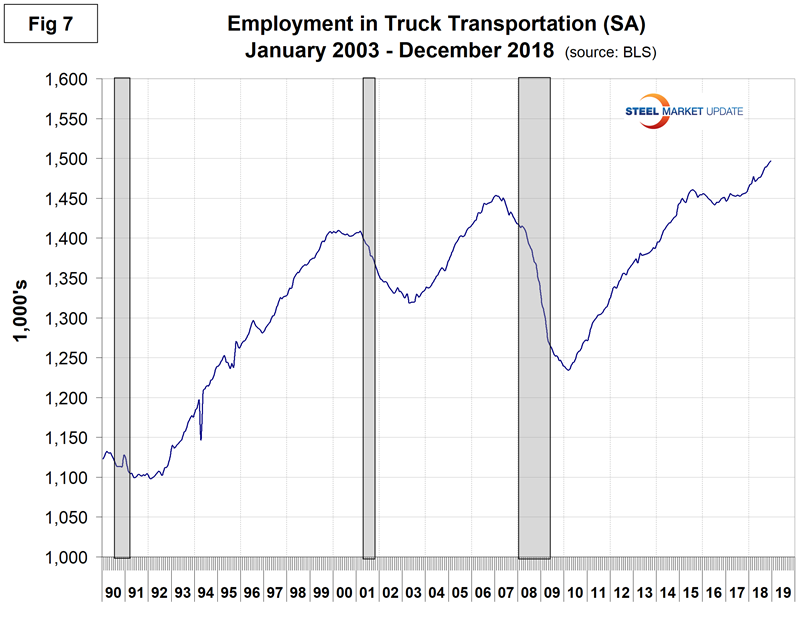

Employment in Trucking: Figure 7 shows total truck driver employment as reported monthly by the BEA. As a measure of economic activity, this indicator has predicted the last three recessions and at present is showing no sign of a slowdown.

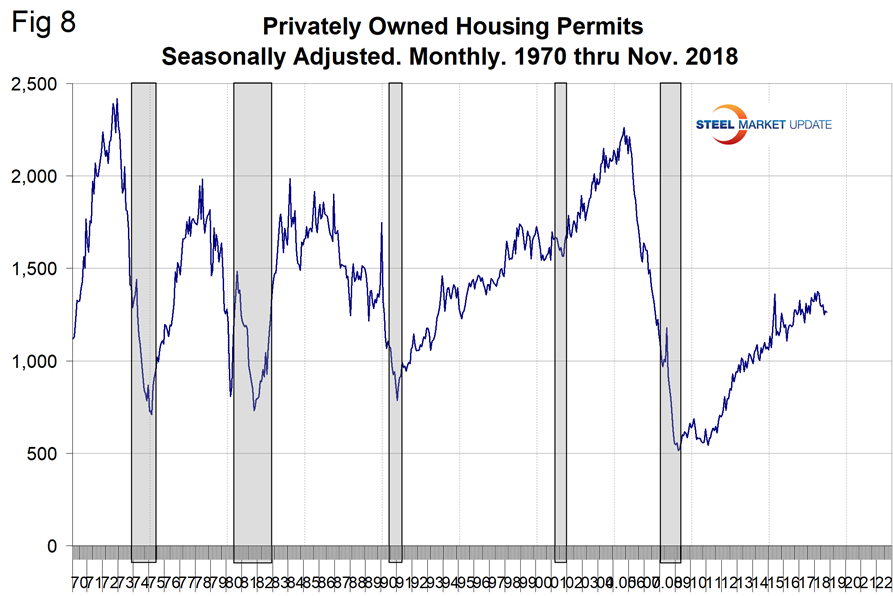

A decline in housing starts has led every recession since 1970. This seems to be a very prescient indicator. At present there is evidence of slowing, but no sustained decline. In our last report, we changed our analysis from starts to permits to try to be ahead of the game. On a year-over-year basis, growth still looks good, but in the shorter term a slowdown is beginning to appear (Figure 8)

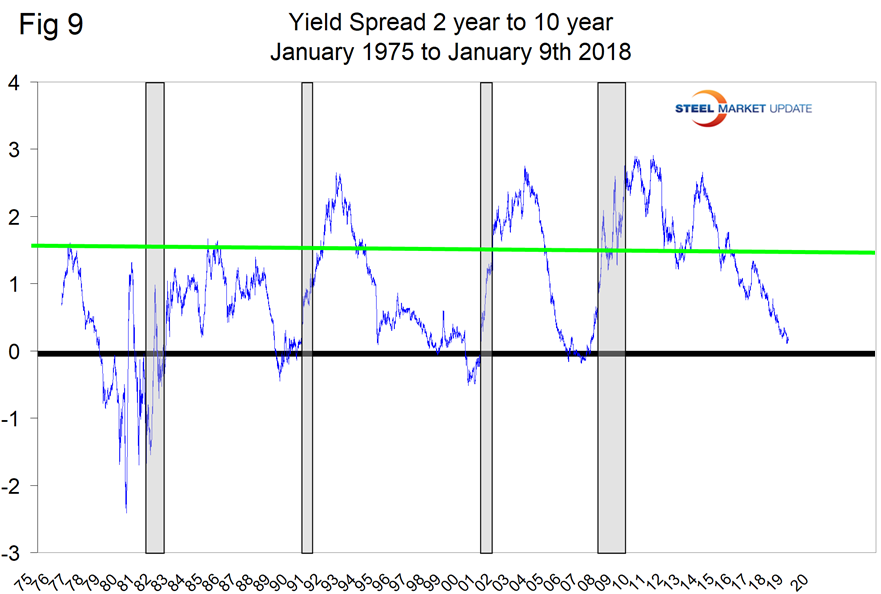

Historically, the most accurate recession predictor has been the bond market, because this massive capital market determines government and business borrowing rates. This is why the famous yield curve has been able to predict every recession since the mid ’60s with a 6- to 24-month lead time (and just one false positive). Or to put another way, if the 2/10 yield curve inverts, there’s a 90 percent historical probability that a recession is coming in the next two years.

Recently, John Rubino, a long horizon equities analyst wrote: “Banks–the main driver of our hyper-financialized society–still make at least some of their money by borrowing short and lending long. They take money that’s deposited into savings accounts and short-term CDs (or borrowed in the money markets) and lend it to businesses and home buyers for years or decades. In normal times, long-term rates are higher than short-term to compensate lenders for tying their money up for longer periods. The banks earn that spread, which can be substantial if borrowers make their payments. When the yield curve flattens and then inverts–that is, when short rates exceed long rates–banks lose the ability to make money this way. They lend less, which restricts building and buying and spooks the broader markets.”

The Treasury spread is developed by subtracting a shorter-term from a longer-term Treasury yield. Ten-year interest rates minus two-year interest rates, for example, as shown in Figure 9. A spread that is increasing is a sign of higher growth and inflation as bank lending becomes more profitable (borrow short and lend long) and loan growth is expected to accelerate. A declining or contracting yield spread foreshadows lower growth and inflation as a result of contractions in bank loan growth due to reduced profitability. The current forecast predicts lower growth and inflation will materialize in 2019. That thesis has been unfolding as the yield curve is contracting. Prior to the last few weeks, the Fed was signaling that it would raise rates several more times in 2019. This policy is now being re-examined.

According to a Reuters poll of more than 70 bond market strategists taken Dec. 6-12, the U.S. Treasury yield curve will invert in 2019, possibly within the next six months, much earlier than forecast just three months ago, with a recession to follow as soon as a year after that. Those expectations come on the heels of a deep sell-off in global stocks and the flattening of the U.S. yield curve, with the gap between longer-dated and shorter-dated yields narrowing to its smallest in more than a decade. Some maturities on the curve, notably yields on 2- to 5-year notes have already flipped. An inversion between 2- and 10-year yields is a closely watched signal as that has preceded almost all the American recessions of the past half century. The U.S. economy, currently in its second-longest expansion on record, has been juiced late in the cycle by the Trump administration’s tax cuts, and is expected to slow sharply by the end of next year as that stimulus fades. “We are going to experience or will get closer to yield inversion by the middle of next year or maybe even a little bit earlier,” said Elwin de Groot, head of macro strategy at Rabobank. “We already see growth slowing down next year and further in 2020. We are not yet forecasting a recession in the United States, but the risks have clearly increased and that is going to be reflected in the shape of the yield curve.” The two-year Treasury yield is forecast to rise to 3.20 percent in the next 12 months, from around 2.78 percent in early December. The 10-year bond yield was expected to rise to 3.30 percent from about 2.90 in a year. While there is no set pattern on how long it takes for a recession to hit once the yield curve has flipped, it took about 18 months before the last deep recession about a decade ago. Just in the last three months, the yield spread has collapsed by two-thirds from just over 30 basis points. That has coincided with one of the most tumultuous periods on global equity markets since late August. Thirty of more than 40 strategists who answered an extra question in the Reuters poll expect the 2s-10s yield spread to become negative in the next 12 months, including 15 who said within the next six months. The other 10 strategists said it would take two years or more.

Half of 26 strategists in the poll expect a U.S. recession to follow that inversion within the next two years. The other half said it would take three years or more.

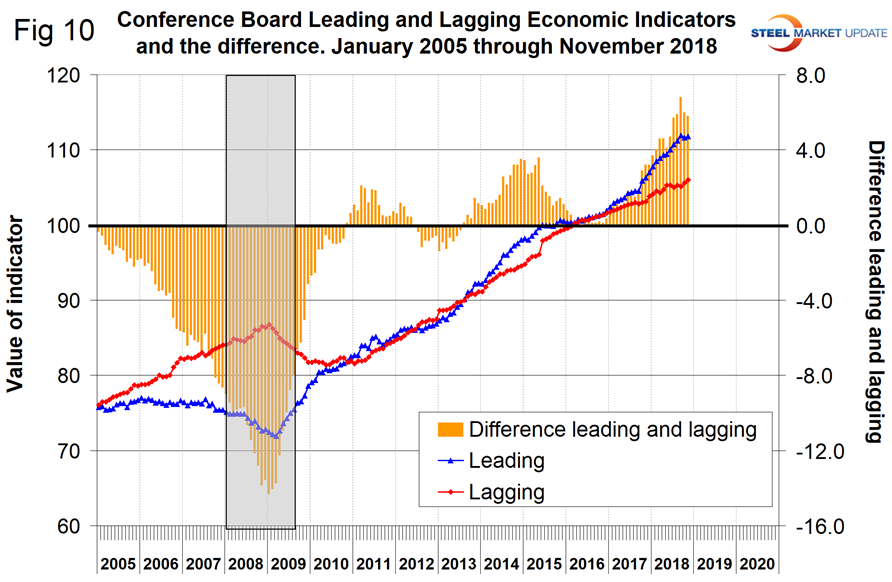

Figure 10 is the chart we like the best, though we have no history before 2008. This is The Conference Board leading and lagging economic index. We have subtracted one from the other in the rationale that if the lead is better than the lag, the situation is improving, or vice versa. The lead minus lag inverted three years in advance of the 2008 recession; certainly by 18 months before the big event it was clear something was happening. Through November, the spread was very healthy and has been widening for almost two years.

SMU Comment: Clearly, markets are becoming more nervous, but taken as a whole our eight indicators don’t signal a recession for at least the next six months. The U.S. economy is generally healthy, but the yield spread and housing market bear watching.