Market Data

April 23, 2018

IMF: World Economy Shows Momentum

Written by Peter Wright

The International Monetary Fund has made an upward revision to its forecast for global GDP growth in 2018 and 2019.

The IMF updates its World Economic Outlook (WEO) in April and October each year. The IMF blog last Tuesday stated: “The world economy continues to show broad-based momentum. Against that positive backdrop, the prospect of a similarly broad-based conflict over trade presents a jarring picture. Three months ago, we updated our global growth forecast for this year and next substantially, to 3.9 percent in both years. That forecast is being borne out by continuing strong performance in the euro area, Japan, China and the United States, all of which grew above expectations last year. We also project near-term improvements for several other emerging-market and developing economies, including some recovery in commodity exporters. Continuing to power the world economy’s upswing are accelerations in investment and, notably, in trade. Looking at the largest economies, our 2018 growth projections, compared with our earlier October 2017 projections, are 2.4 percent for the euro area (up by 0.5 percentage point), 1.2 percent for Japan (up by 0.5 percentage point), 6.6 percent for China (up by 0.1 percentage point), and 2.9 percent for the United States (up by 0.6 percentage point). U.S. growth will be boosted in part by a largely temporary fiscal stimulus, which explains over one-third of our upgrade over last October for 2018 global growth. Despite the good near-term news, longer-term prospects are more sobering. Advanced economies—facing aging populations, falling rates of labor force participation, and low productivity growth—will likely not regain the per capita growth rates they enjoyed before the global financial crisis. Emerging and developing economies present a diverse picture and among those that are not commodity exporters, some can expect longer-term growth rates comparable to pre-crisis rates. Many commodity exporters will not be so lucky, however, despite some improvement in the outlook for commodity prices. Those countries will need to diversify their economies to boost future growth and resilience.”

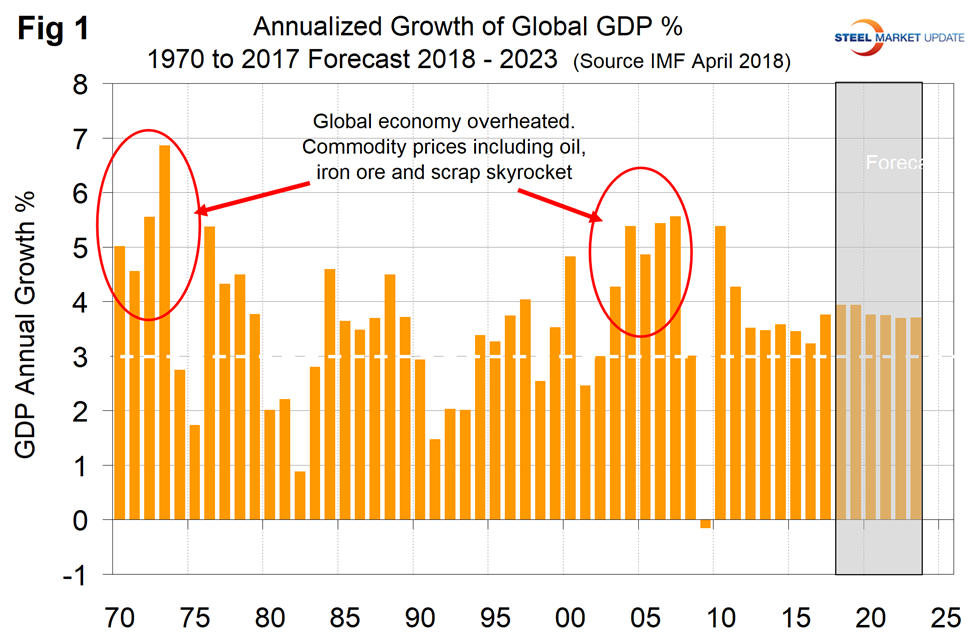

SMU Data Analysis: Figure 1 shows the growth of global GDP since 1970 with this month’s IMF forecast through 2023. We have highlighted the periods of the early 1970s and the mid-2000s when the commodity bubbles prevalent at those times were driven by unusually high and sustained global growth. The collapse of the commodity bubble in the last decade coincided with the U.S. banking and housing crisis setting up the perfect storm. After the rebound in 2010, global growth declined through 2016 and is now forecast to expand at close to 4.0 percent this year and next, then to decline through 2023.

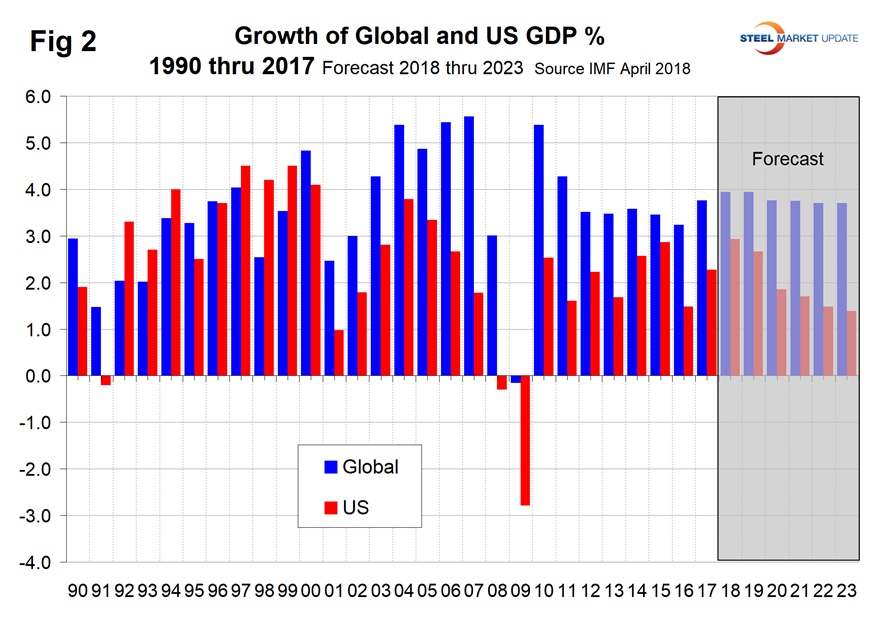

Prior to the 2001 recession, the U.S. held its own in the economic growth stakes. But between 2001 and 2008, growth in the U.S. averaged 1.84 percent less per year than the growth of the global economy as a whole (Figure 2). In the years 2011 through 2015, the gap narrowed to 0.76 percent. The difference is forecast to widen to 2.32 percent in 2023.

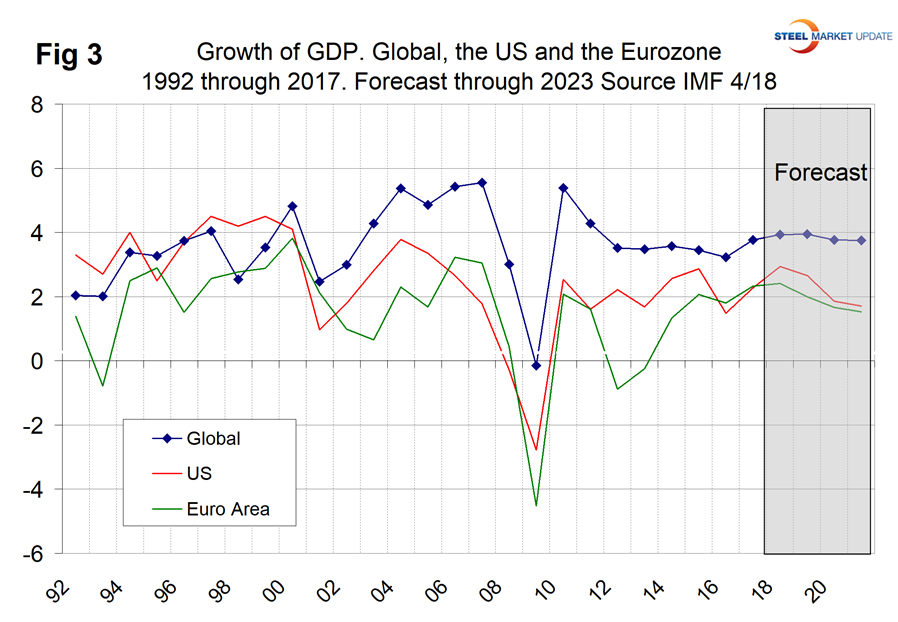

The U.S. has outperformed the Eurozone since 2010 and in 12 of the 15 years through 2023 will continue that trend (Figure 3).

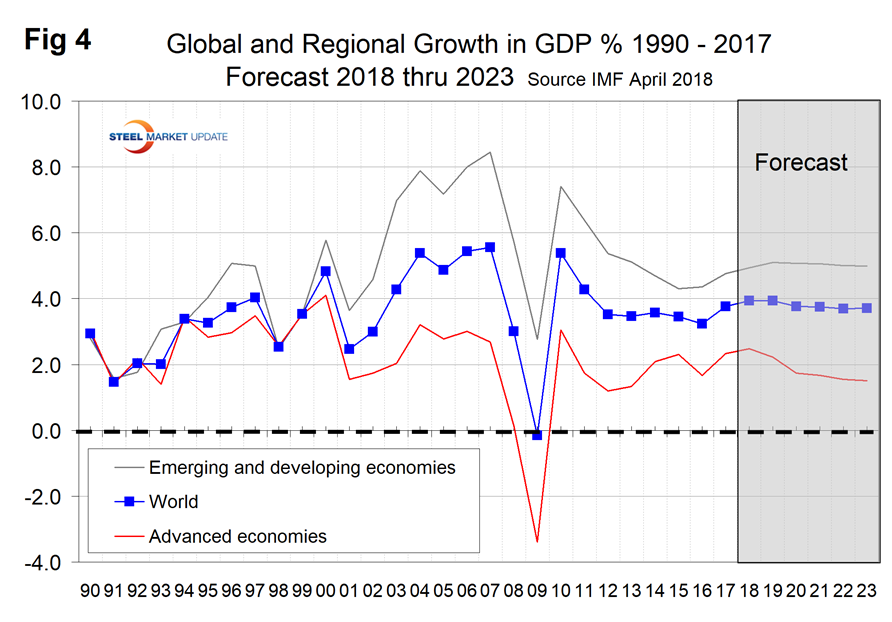

Figure 4 shows the growth comparison between emerging and developing economies and the advanced economies. That gap is projected to widen through 2023.

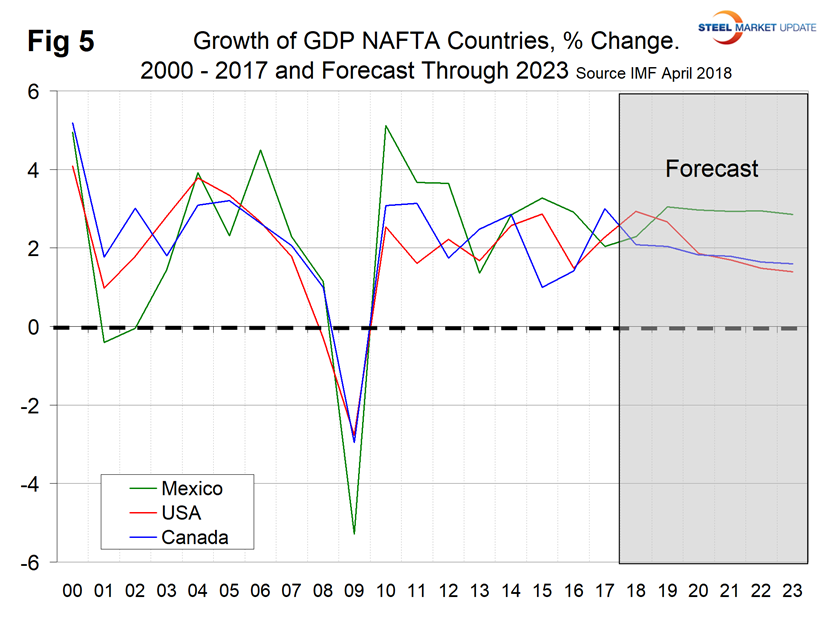

Within NAFTA, Canada had the highest rate of growth in 2017; the U.S. is forecast to lead in 2018 and Mexico to lead in the years 2019 through 2023. The U.S. is forecast to be in last place in the years 2021, 2022 and 2023 (Figure 5).

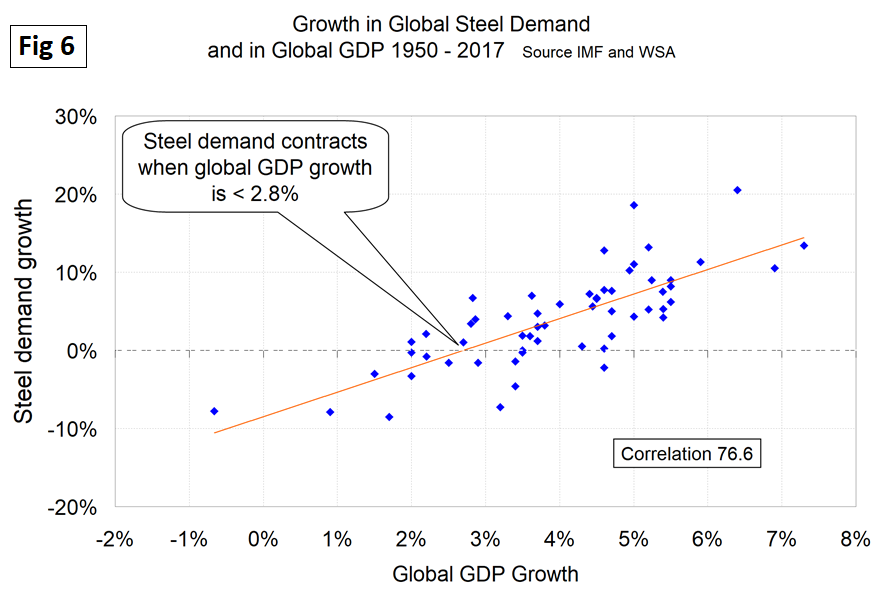

There is a relationship between the growth of GDP and steel demand at both the international and national levels, which also extends to other commodities such as cement. There are two interesting aspects to this relationship. First, the cyclical change in steel demand is vastly more volatile than the change in GDP, which we attribute to the inventory response throughout the supply chain. Secondly, as discovered by our friends at “Steel Guru,” 1 percent growth in GDP does not result in 1 percent growth in steel demand. At the global level, it takes a 2.8 percent increase in GDP to get any increase in steel demand (Figure 6). This is a long-term average over a period of 65 years and based on the added volatility of steel can be a predictor of the immediate future. For example, after the disastrous decline in steel demand in 2009, there was no doubt that a huge cyclical rebound would occur as inventory managers throughout the world began to react to the economic recovery. If the IMF forecast proves to be correct, then the growth in global steel demand will be around 3 percent annually through 2023.

In the U.S. steel market, it requires about 2.2 percent growth in GDP to generate growth in steel demand. Therefore, if current forecasts prove to be correct, we can expect steel demand to be relatively strong this year, then tail off through 2023.