Product

February 6, 2018

Construction Spending Shows 1.4% Growth in December

Written by Peter Wright

In December, total construction spending expanded by 1.4 percent year over year. Viewed in the longer term, however, the growth rate is slowing. The growth of total construction on a rolling 12-month basis year over year slowed every month in 2017. On a rolling three-months basis, growth improved in October and December. On this three-month basis, growth in August and September was the lowest since November 2011.

Construction expenditures data is developed by the Department of Commerce and is referred to as construction put in place (CPIP). Since construction is extremely seasonal, the growth or contraction we report in this analysis has had seasonality removed by providing only year-over-year comparisons.

![]() At SMU, we analyze the CPIP data to provide a clear description of construction activity, which accounts for about 45 percent of total U.S. steel consumption. See the end of this report for more detail on how we perform this analysis and structure the data. In particular, note that we present nonseasonally adjusted numbers. Much of what you will see in the press may differ from our presentation because others base their comments on adjusted values. Our rationale is that construction is highly seasonal and our businesses function in a seasonal world.

At SMU, we analyze the CPIP data to provide a clear description of construction activity, which accounts for about 45 percent of total U.S. steel consumption. See the end of this report for more detail on how we perform this analysis and structure the data. In particular, note that we present nonseasonally adjusted numbers. Much of what you will see in the press may differ from our presentation because others base their comments on adjusted values. Our rationale is that construction is highly seasonal and our businesses function in a seasonal world.

Total Construction

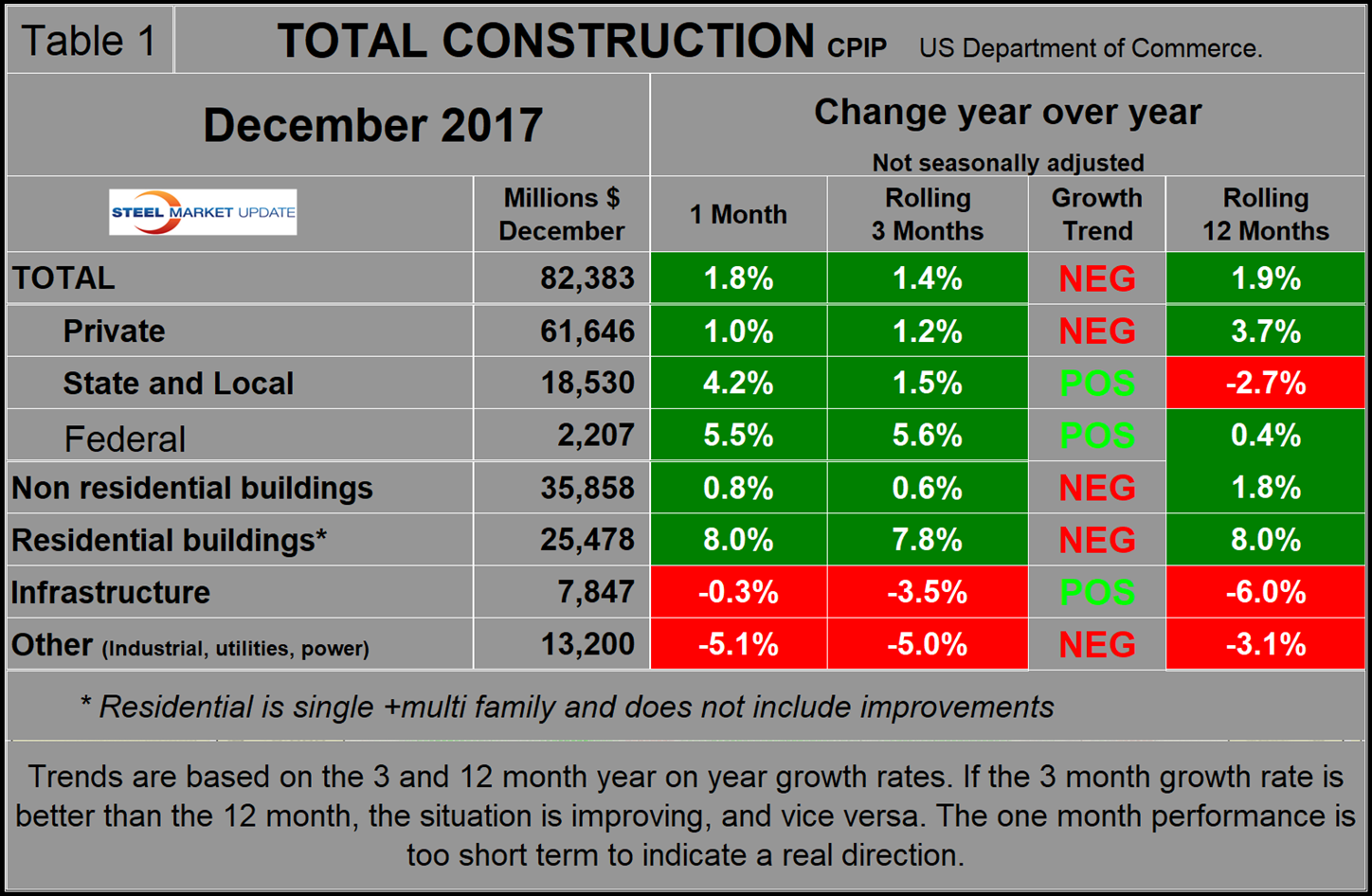

Total construction expanded by 1.4 percent in three months through December year over year, which was up from 1.1 percent in November. Growth slowed from 7.5 percent in January to 0.5 percent in August, which was the month with the lowest growth since November 2011. On a rolling 12-months basis year over year, growth in December was 1.9 percent, the lowest growth rate on a 12-month basis since March 2012. Since the three-month growth rate is lower than the 12-month rate, we conclude that in the long term the rate of growth is slowing. We describe this as negative momentum. December construction expenditures totaled $82.4 billion, which breaks down to about $61.6 billion of private work, $18.5 billion of state and locally funded (S&L) work, and $2.2 billion of federally funded work (Table 1). Growth trend columns in all four tables in this report show momentum.

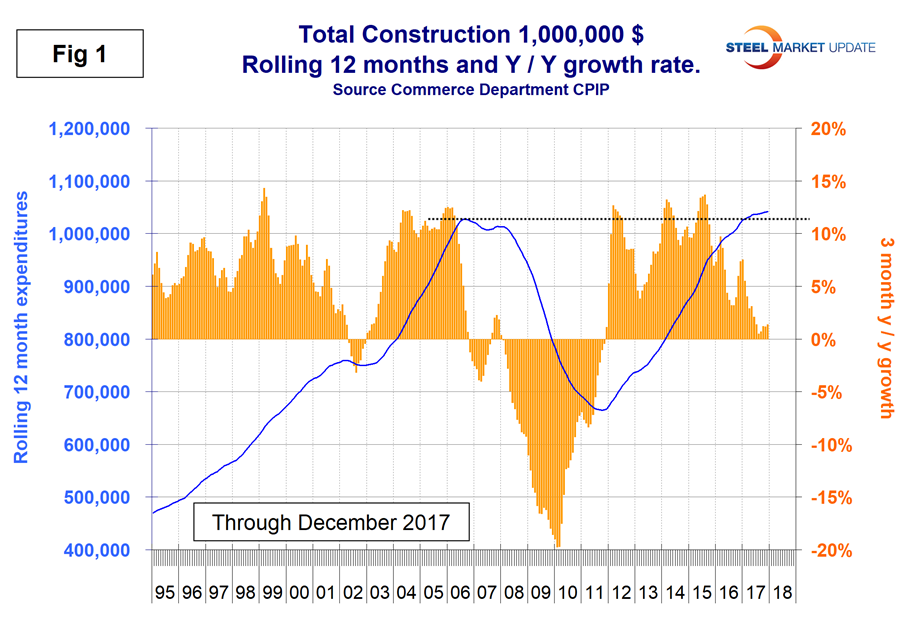

Figure 1 shows total construction expenditures on a rolling 12-month basis as the blue line and the rolling three-month year-over-year growth rate as the brown bars. Figures 1 through 4 in this analysis have the same format, the result of which is to smooth out variation and eliminate seasonality. We consider four sectors within total construction: nonresidential, residential, infrastructure and other. The latter is a catchall and includes industrial, utilities and power. Of these four sectors, residential buildings and infrastructure had positive momentum in the December data.

The pre-recession peak of total construction on a rolling 12-month basis was $1.028 trillion through November 2006. The low point was $665.1 billion in the 12 months through April 2011. The months August 2016 through December 2017 on a rolling 12-month basis each exceeded $1 trillion. In 12 months through December 2017, construction expenditures totaled $1.042 trillion. (This number excludes residential improvements; see explanation below.)

Private Construction

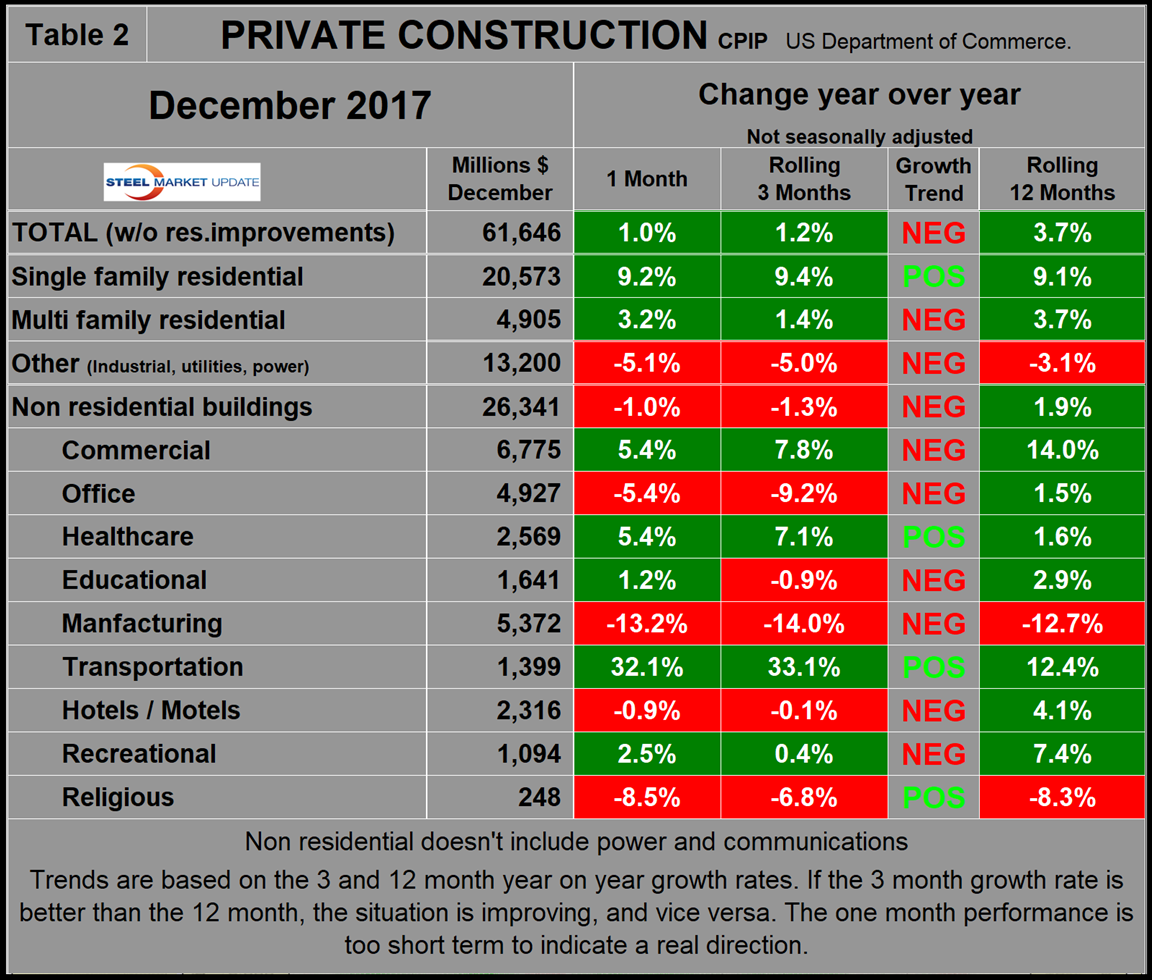

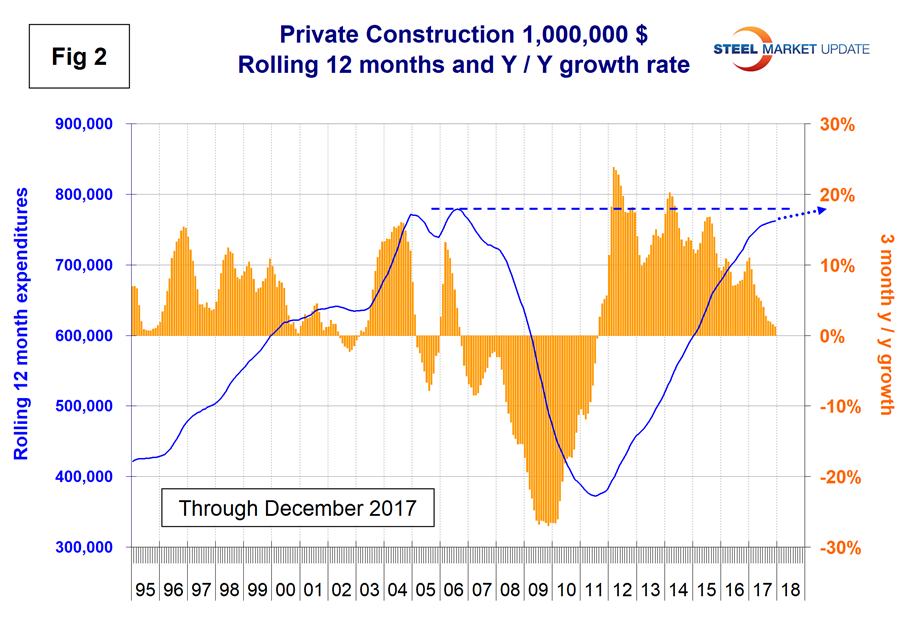

Table 2 shows the breakdown of private expenditures into residential and nonresidential and subsectors of both. The growth rate of private construction in three months through December 2017 was 1.2 percent, down from 11.0 percent in the three months through January 2017, as shown by the brown bars in Figure 2. At the present rate, it will be well into 2019 before private construction exceeds pre-recession expenditures.

Excluding property improvements, our report shows that single-family residential grew by 9.4 percent with positive momentum and multifamily residential contracted by 1.4 percent with negative momentum. Homebuilder sentiment is high, suggesting that the U.S. housing market is well-positioned for growth over the coming months. We have a problem with this conclusion because of the likely effect of the 2018 tax bill (see below). The NAHB housing market index stood at 74 in December—the highest level since July 1999 before declining to 72 in January. Expectations for the next six months and buyer traffic in January were high. On a three-month moving average basis, all four regional NAHB indexes are rising, particularly the North East which was lagging in mid-2017. In our last report, we quoted equities analyst Wolf Richter, whose insight is worth repeating: “The new tax law represents a momentous change for how housing will be promoted in the future. The relentless wisdom that buying a home is the smart tax-thing to do will no longer apply for most households. The new law also reduces or eliminates the highly touted tax benefits of debt. Over the years, this will gradually shape how homeownership is being perceived. And I think the enormity of this change has not been fully appreciated yet.”

The Census Bureau reports on construction starts in its analysis. In the starts data, the whole project is entered into the database when ground is broken. Construction put in place is based on spending work as it occurs; the value of a project is spread out from the project’s start to its completion. Single-family starts grew at 5.3 percent in the three months through December, which was less than the growth rate of CPIP, suggesting that housing will slow in coming months. Multifamily starts contracted by 13.0 percent in December, which was much worse than the small growth of CPIP, suggesting that multifamily will continue to see a slowing market in 2018.

Within private nonresidential buildings, commercial, healthcare, transportation terminals and religious buildings had positive momentum, but all the other sectors are slowing. The fourth-quarter Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Survey indicated there is currently a net decrease in demand for construction and land development loans, though terms for such loans are easing. The Fed survey reviews changes in the terms of, and demand for, bank loans to businesses on a quarterly basis based on the responses from 73 domestic banks and 24 U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks.

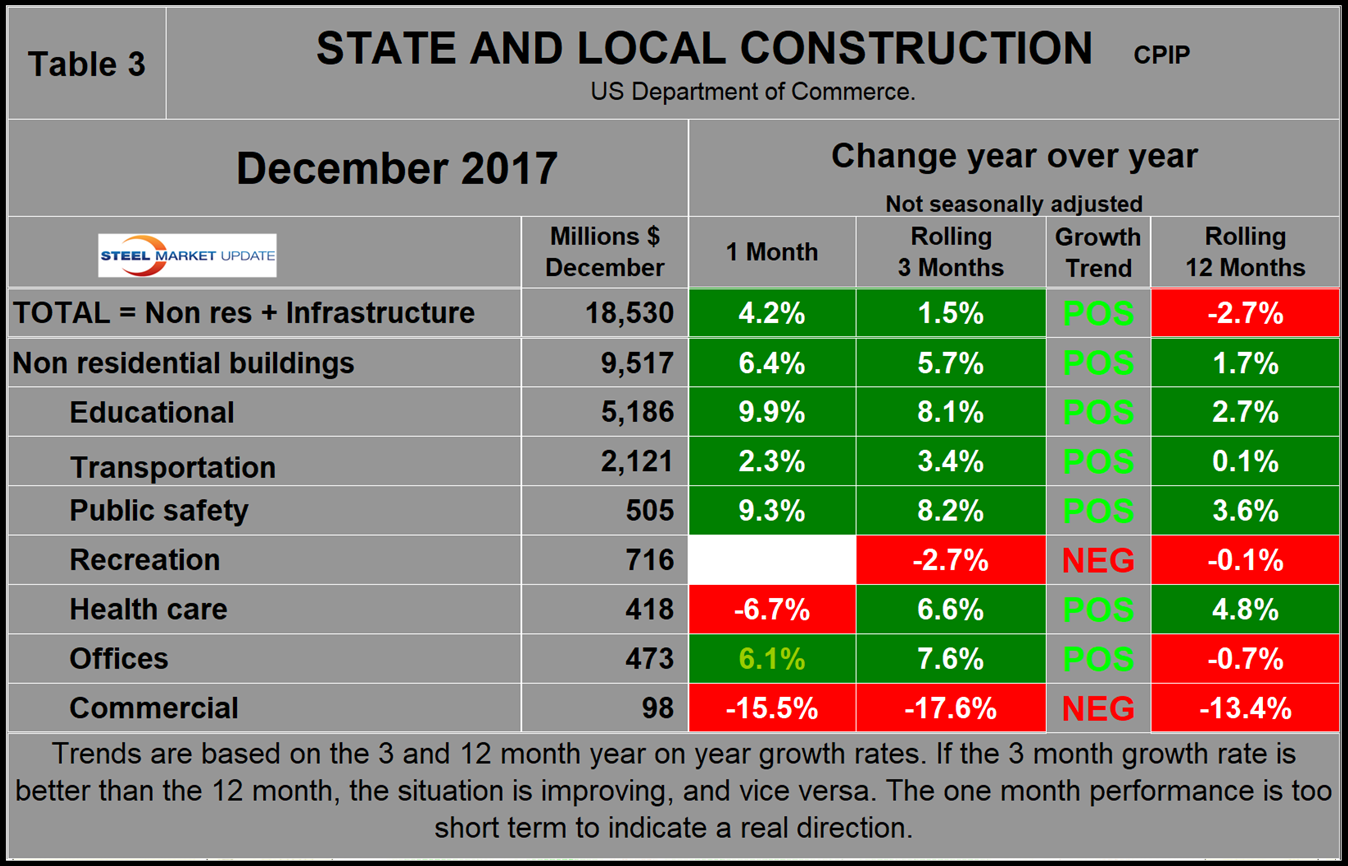

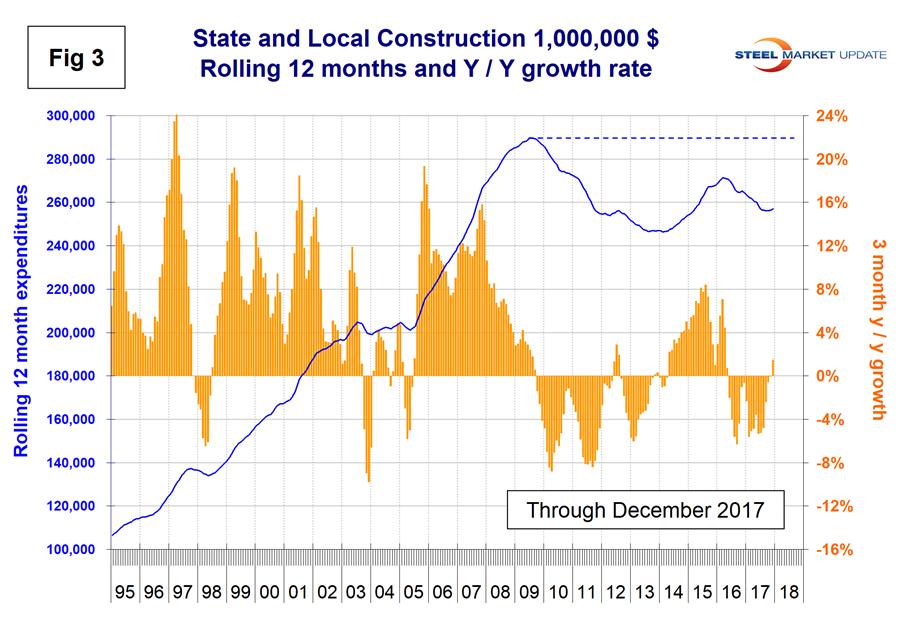

State and Local Construction

S&L work expanded by 1.5 percent in the rolling three months through December year over year with positive momentum. However, this was the first month with positive growth since May 2016 (Table 3). The improvement was driven by nonresidential buildings. The overall S&L figure includes both nonresidential buildings and infrastructure. Figure 3 shows growth as the brown bars and the rolling 12-month expenditures as the blue line. Nonresidential buildings expanded by 5.7 percent in three months through December, which was the best result since September 2015. Total S&L nonresidential buildings slumped in the period May 2016 through September 2017, therefore our year-over-year comparisons will probably look good for the next few months. Educational buildings, by far the largest subsector of S&L nonresidential at $5.2 billion in December, experienced 8.1 percent positive growth on a rolling three months basis with positive momentum.

Comparing Figures 2 and 3, S&L construction did not have as severe a decline as private work during the recession and private work bounced back faster. The downturn in S&L (including infrastructure) means that a full recovery to the pre-recession level of expenditures won’t be achieved until well into the next decade.

Drilling down into the private and S&L sectors as presented in Tables 2 and 3 shows which project types should be targeted for steel sales and which should be avoided. There are also regional differences to be considered, data for which is not available from the Commerce Department.

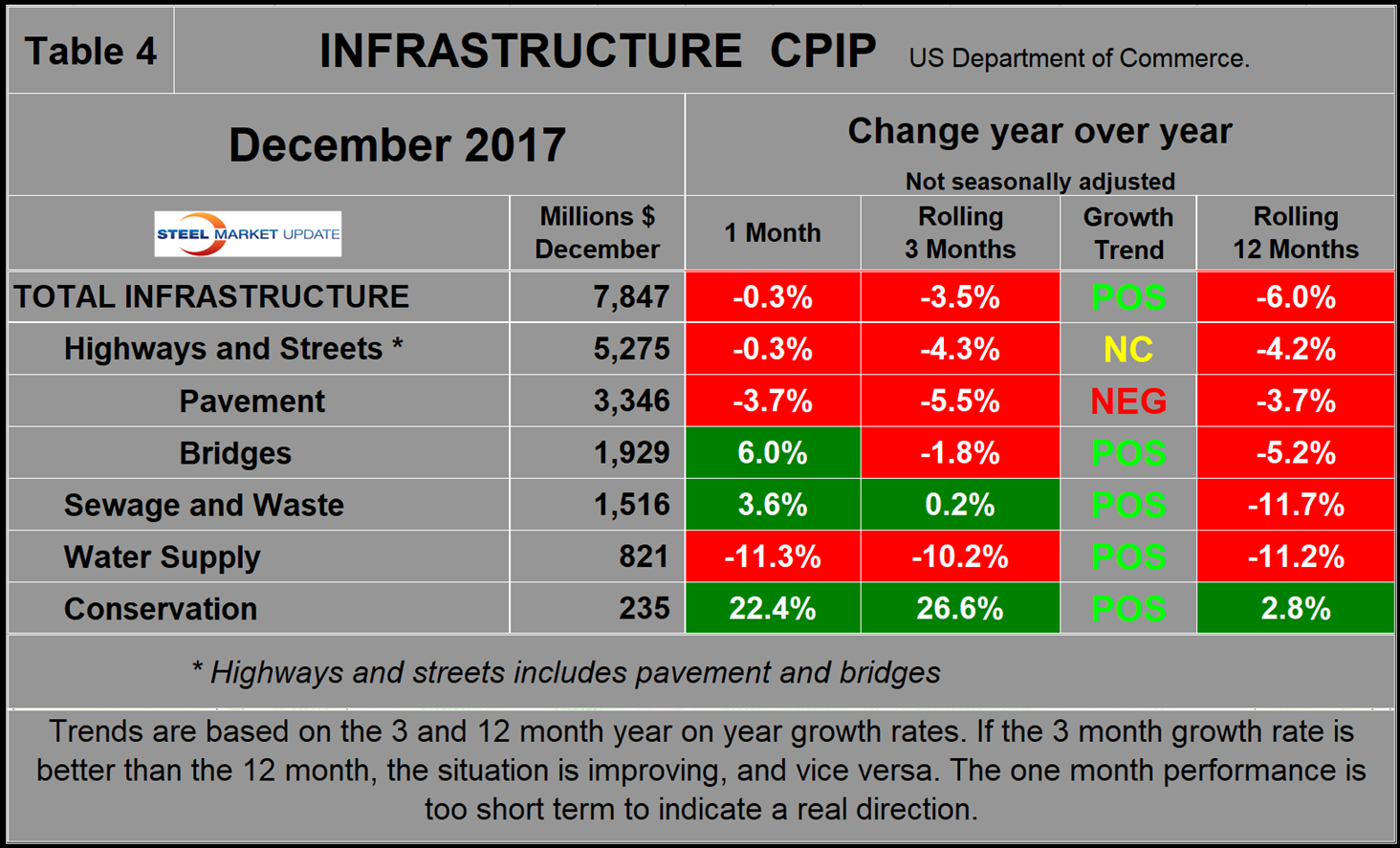

Infrastructure

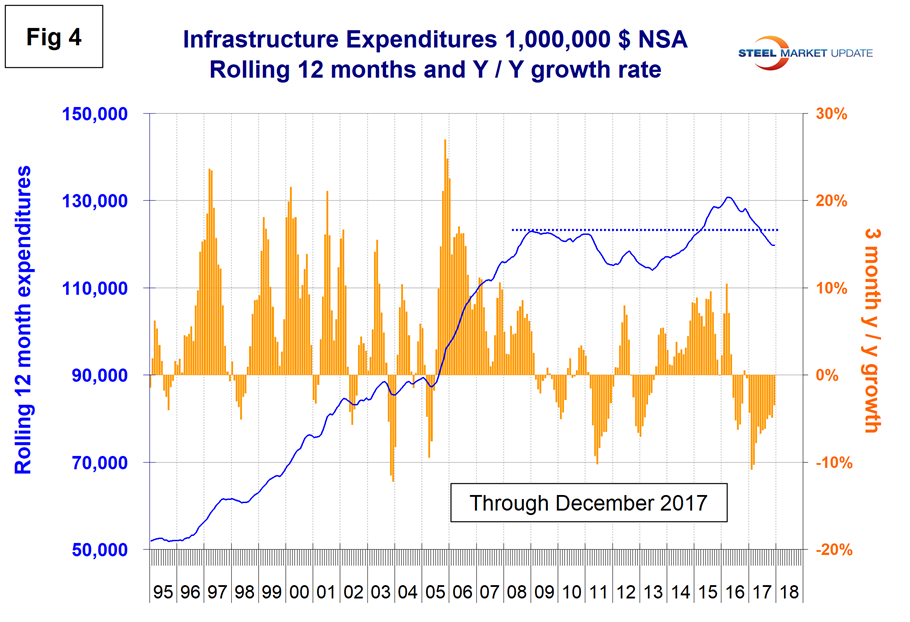

Infrastructure expenditures had positive growth in the first eight months of 2016 and have experienced negative growth since then. In the December data, every subsector of infrastructure except sewage and waste and conservation contracted. Highways and streets including pavement and bridges account for about two-thirds of total infrastructure expenditures. Highway pavement is the main subcomponent of highways and streets and had a 4.3 percent contraction in three months through December. Bridge work contracted by 1.8 percent, which was the 21st straight month of contraction (Table 4). In many categories such as health care, education and multifamily residential, the Commerce Department separates private and publicly funded projects. Unfortunately, they don’t do this with infrastructure, which is all lumped under S&L. If Texas (where this writer resides) is typical, there is a huge amount of private money going into infrastructure, which means that the contraction in the S&L component may be much more severe than the CPIP reports indicate.

Infrastructure expenditures peaked in the rolling 12 months through April 2016 and have since declined to a level lower than the previous peak in January 2009 (Figure 4). In this analysis, we have been asking ourselves for months why the $305 billion authorized in December 2015 by Congress to fund roads, bridges and rail lines had no beneficial effect on infrastructure expenditures. This month we came across a paper by the St. Louis Fed that asked why the Obama stimulus bill of 2009 had no effect on highway spending. We are extrapolating this thinking to include the 2015 authorization. Here is a synopsis of the St. Louis Fed’s conclusions: “So, why didn’t the Recovery Act substantially increase overall highway spending? The answer may lie in a concept economists call crowding out. In the context of infrastructure spending, crowding out occurs when increased government spending reduces spending from other sources. In effect, we would see federal funds replace—or crowd out—state funds. In the aftermath of the 2007-09 recession, state governments faced drastic declines in tax revenue and would have had ample incentives to repurpose additional highway funds elsewhere. Concerns about crowding out were central to the policy debate surrounding the bill, and a provision of the act, the Maintenance-of-Effort Requirement, was intended to address such concerns. The requirement stated that, as a condition of receiving funding, each state’s governor had to certify that state’s intention to maintain its contribution to each transportation category (e.g., highways, mass transit, airports) by May 19, 2009. However, states were not required to maintain pre-act spending levels. Rather, governors could commit to spending less than in recent years if the reduction was justifiable based on other fiscal considerations. Additionally, the act contained no requirements on the share of spending made up by state vs. federal funds. The act states, ‘the federal share payable on account of any project or activity carried out…shall be, at the option of the recipient, up to 100 percent of the total cost thereof.’ To assess the prevalence of crowding out, Dupor (2017) examines whether states that received relatively more Recovery Act highway aid spent relatively more on highway improvements. In the article, the estimated effect of FHWA aid received on highway spending is 0.19, meaning that a one dollar increase in FHWA raised highway spending by only 19 cents. This implies that for each dollar received, state governments cut their own contribution to highway infrastructure by 81 cents. Further, because the estimate is not statistically significant from zero, the hypothesis of a complete crowding out of state highway spending by Recovery Act highway funds cannot be rejected. In practice, little of the Recovery Act’s highway funds were actually spent on improving highways. The language of the act itself, as well as incentives for states to repurpose funds, led to overall highway spending levels that were very likely similar to what they would have been without the stimulus. The inability of the Recovery Act to substantially improve U.S. highways serves as a reminder that crowding out is a potential problem for any government stimulus and that seemingly small details in legislation can have significant economic consequences.”

The 2015 five-year infrastructure bill was the largest reauthorization of federal transportation programs approved by Congress in more than a decade, ending an era of stopgap bills and half-measures that left the Highway Trust Fund nearly broke and frustrated local governments and business groups.

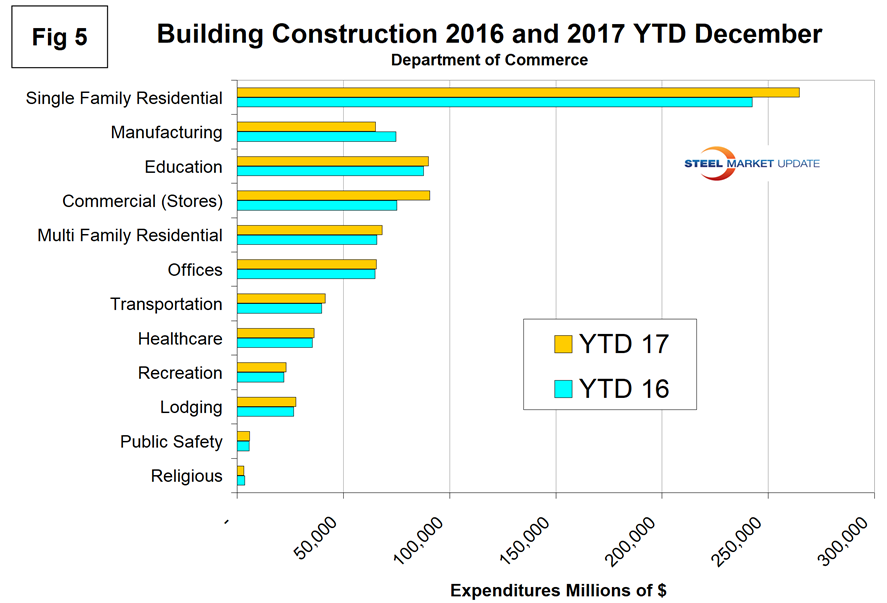

Total Building Construction Including Residential

Figure 5 compares year-to-date expenditures for building construction for 2016 and 2017. Single-family residential is dominant and in the 12 months of 2017 totaled $264.5 billion, up from $242.5 billion in 2016. It seems likely that the 2018 tax bill, by its reduction in the deductibility of mortgage interest and local taxes, will negatively affect single-family home construction.

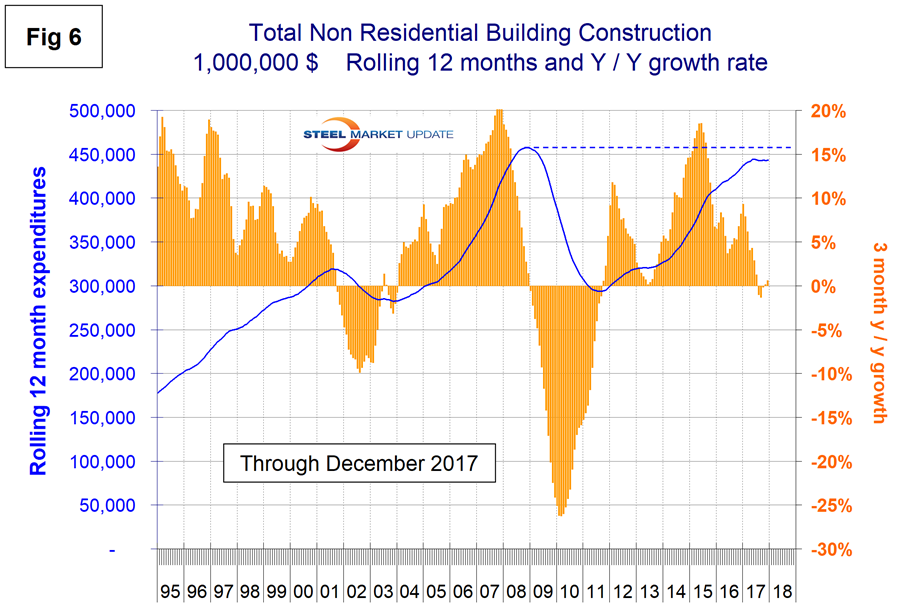

Figure 6 shows total expenditures and growth of nonresidential building construction. Growth has been slowing this year and went negative in the three months through August, September and October year over year for the first time since November 2011. November and December eked out small gains of 0.2 and 0.6 percent, respectively.

Explanation: Each month, the Commerce Department issues its construction put in place data, usually on the first working day covering activity one month and one day earlier. Construction put in place is based on spending work as it occurs, estimated for a given month from a sample of projects. In effect, the value of a project is spread out from the project’s start to its completion. This is different from the starts data published by the Census Bureau for residential construction, by Dodge Data & Analytics and Reed Construction for nonresidential, and Industrial Information Resources for industrial construction. In the case of starts data, the whole project is entered to the database when ground is broken. The result is that the starts data can be very spiky, which is not the case with CPIP.

The official CPIP press release gives no appreciation of trends on a historical basis and merely compares the current month with the previous one on a seasonally adjusted basis. The background data is provided as both seasonally adjusted and non-adjusted. The detail is hidden in the published tables, which SMU tracks and dissects to provide a long-term perspective. Our intent is to provide a route map for those subscribers who are dependent on this industry to “follow the money.” This is a very broad and complex subject, therefore to make this monthly write-up more comprehensible, we are keeping the information format as consistent as possible. In our opinion, the absolute value of the dollar expenditures presented are of little interest. What we are after is the magnitude of growth or contraction of the various sectors. In the SMU analysis, we consider only the non-seasonally adjusted data. We eliminate seasonal effects by comparing rolling three-month expenditures year over year. CPIP data also includes the category of residential improvements, which we have removed from our analysis because such expenditures are minor consumers of steel.

In the four tables included in this analysis, we present the non-seasonally adjusted expenditures for the most recent data release. Growth rates presented are all year over year and are the rate for the single month’s result, the rolling three months and the rolling 12 months. We ignore the single-month year-over-year result in our write-ups because these numbers are preliminary and can contain too much noise. The growth trend columns indicate momentum. If the rolling three-month growth rate is stronger than the rolling 12 months, we define that as positive momentum, or vice versa. In the text, when we refer to growth rate, we are describing the rolling three-month year-over-year rate. In Figures 1 through 4 and 6, the blue lines represent the rolling 12-month expenditures and the brown bars represent the rolling three-month year-over-year growth rates.