Market Data

January 26, 2018

WSA: Global Steel Output Near 1.7 Billion Tons in 2017

Written by Peter Wright

Global steel production grew significantly in 2017, though the pace of growth slowed somewhat in December due to pollution control cutbacks in China, according to the latest Steel Market Update analysis of World Steel Association data.

“Global growth has been accelerating since mid-2016, and all signs point to a further strengthening both this year and next. This is very welcome news,” said Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), on Jan. 22.

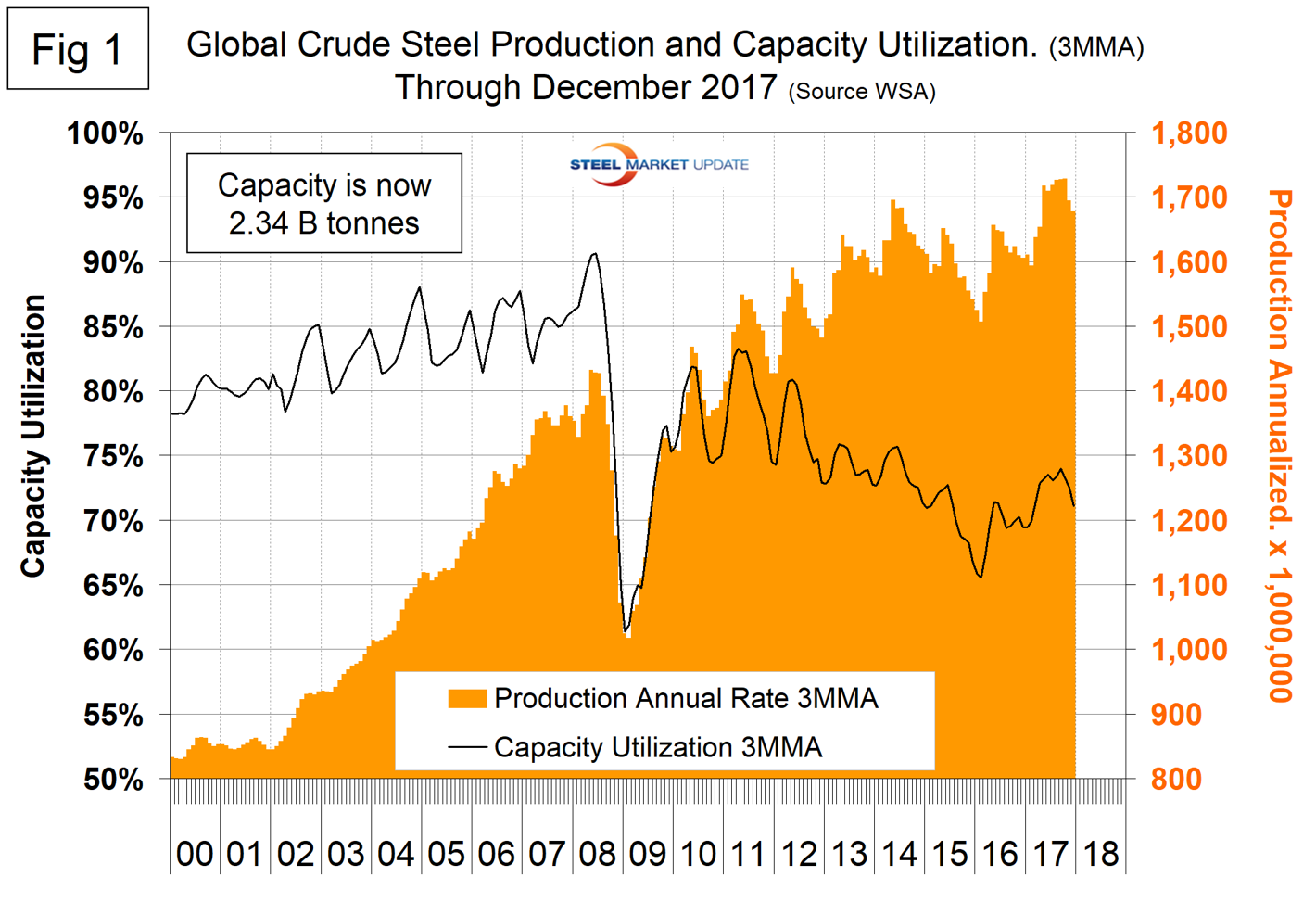

In 2017, global steel production totaled 1.688 billion metric tons, up by 5.2 percent from 2016. Production in the month of December was 138,059,000 metric tons, up from 136,543,000 in November. Capacity utilization decreased from 70.9 percent to 69.5 percent. The three-month moving averages (3MMA) that we prefer to use were 139,807,000 metric tons and 71.1 percent, respectively. Tonnage was up, and capacity utilization was down, because of the extra day in December, which resulted in tons per day declining. Figure 1 shows monthly production and capacity utilization since January 2000.

The summer slowdown that has occurred in each of the last seven years was delayed until November this year. On a tons-per-day basis, production in December was 4.454 million metric tons with a 3MMA of 4.559 million metric tons. The all-time high was in June 2017 at 4.695 million metric tons. In three months through December, production was up by 4.5 percent year over year. Capacity utilization took an erratically downward trajectory from mid-2011 through February 2016 when it bottomed out at 65.5 percent. Apart from the normal end-of-year seasonal decline, there has been a steady improvement since then. In each of the last 10 months, the 3MMA of capacity utilization has been greater than 71 percent for the first time since June 2015. Last December, the OECD’s steel committee estimated that global capacity would increase by almost 58 million metric tons per year between 2016 and 2018 bringing the total to 2.43 billion tons. That forecast is coming to pass as capacity is now 2.38 billion tons.

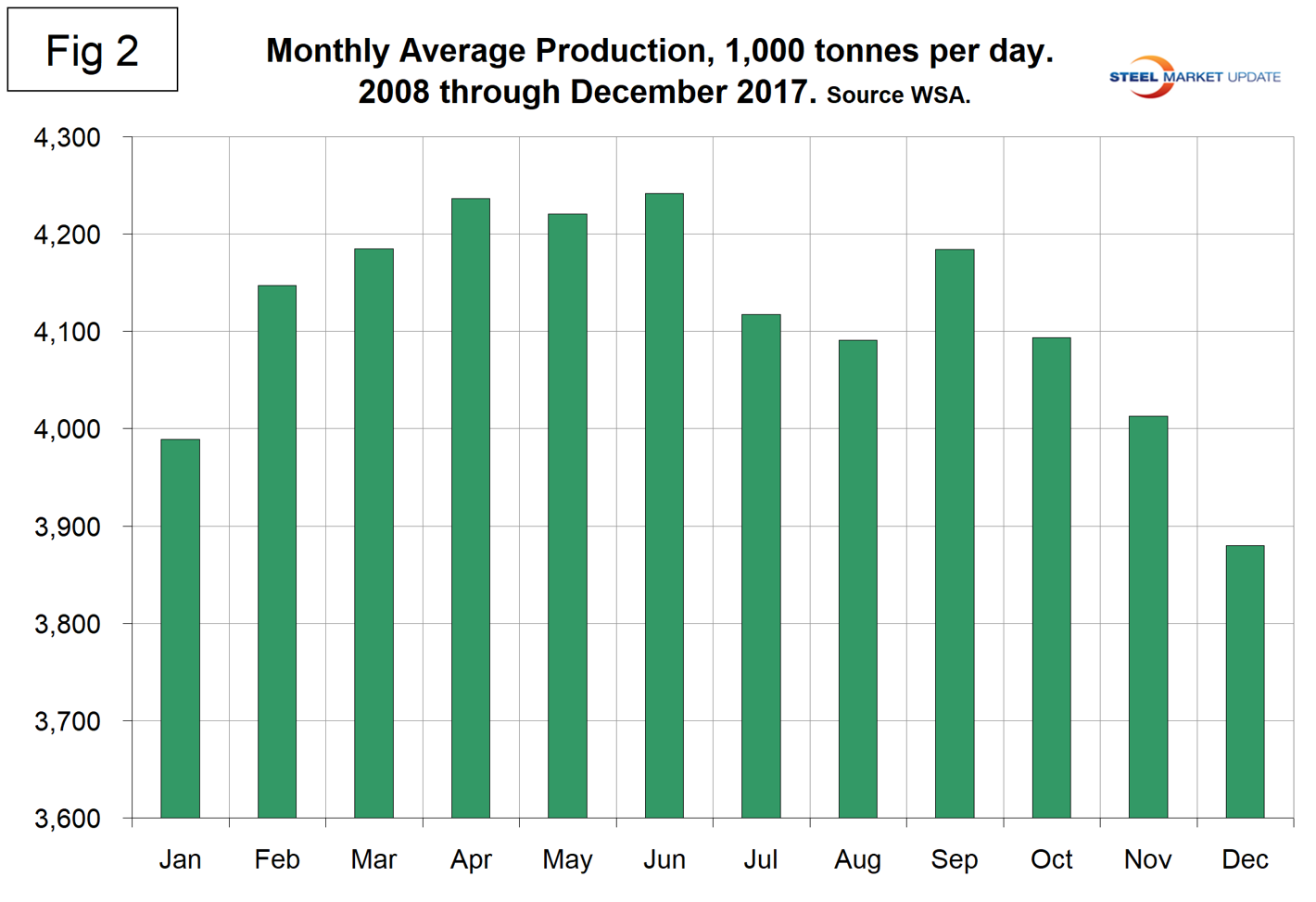

Digging deeper into what’s going on, we start with seasonality. On average, global production has peaked in the early summer for the last seven years with April and June having the highest average volume. Figure 2 shows the average tons-per-day production for each month since 2008. In those 10 years on average, December has been down by 3.3 percent. This year, December was down by 2.15 percent.

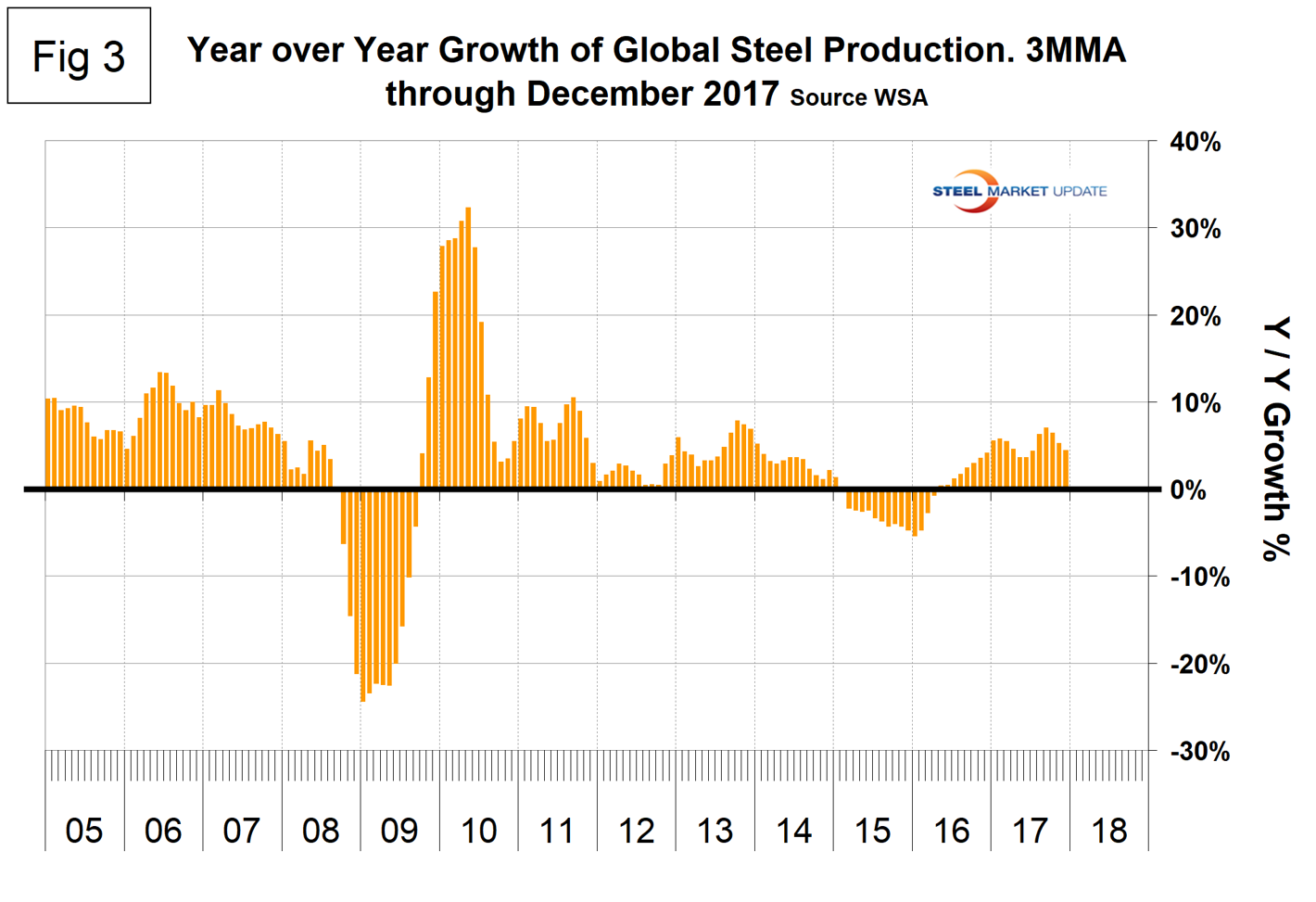

Figure 3 shows the monthly year-over-year growth rate of steel production on a 3MMA basis since January 2005. Production began to contract in March 2015, and the contraction accelerated through January 2016 when it reached negative 5.4 percent. Growth became positive in May 2016 and averaged 5.2 percent in the 12 months of 2017. In the 14 months through May 2017, China’s growth rate was lower than the rest of the world. That changed in the five months through October when China began to pull away again. In November and December, China once again expanded by less than the rest of the world with a growth rate of 2.0 percent compared to 5.7 percent for other nations. In December, China produced 48.6 percent of the global total for steel, down from 51.6 percent in June.

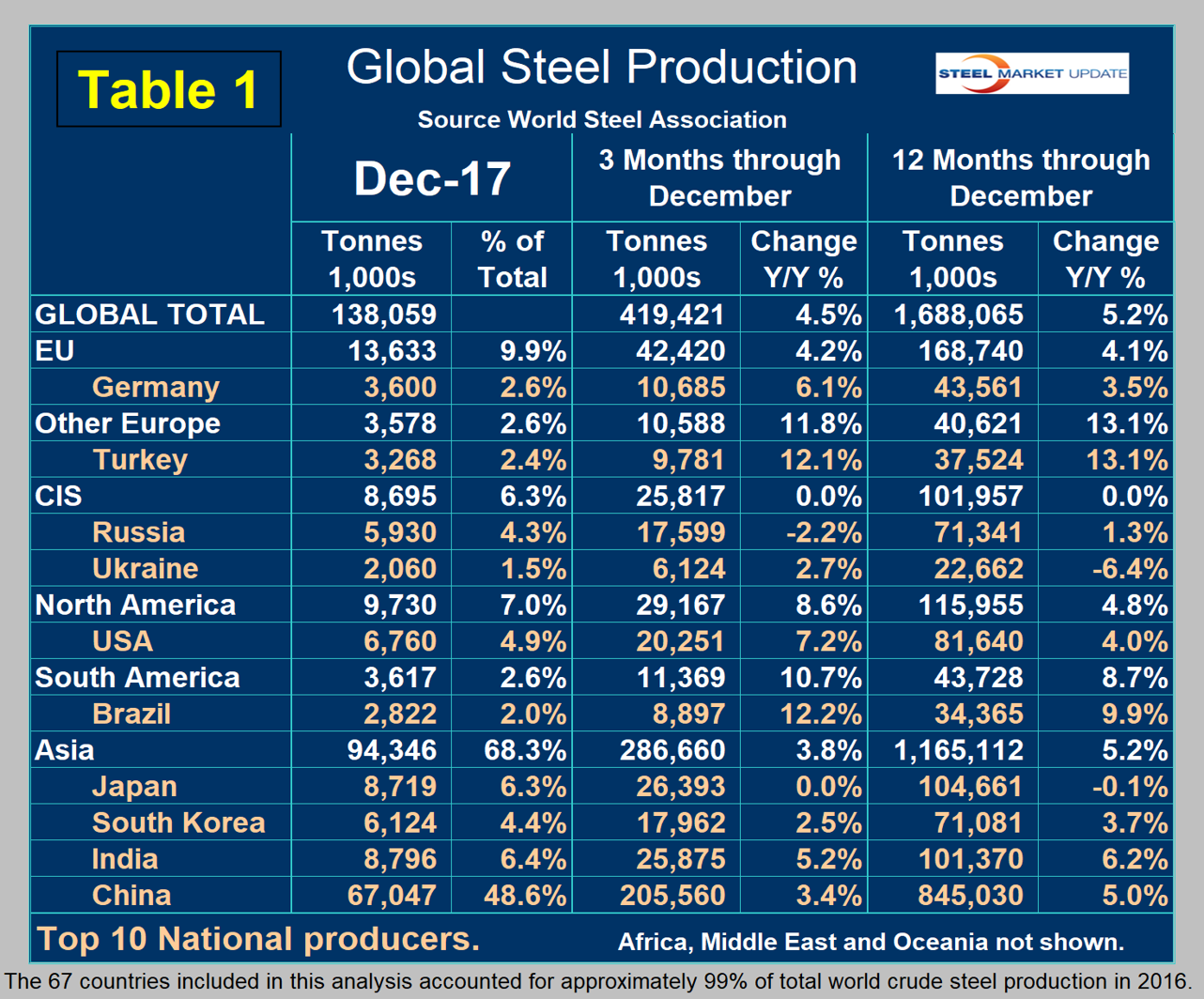

Table 1 shows global steel production broken down into regions, along with the production of the top 10 nations in the single month of December and their share of the global total. It also shows the latest three months and 12 months of production through December with year-over-year growth rates for each period. Regions are shown in white font and individual nations in beige. The world as a whole had positive growth of 4.5 percent in three months and 5.2 percent in 12 months through December. When the three-month growth rate is lower than the 12-month growth rate, as it was in December, we interpret this to be a sign of negative momentum, which is entirely due to China’s pollution-control-driven cutback.

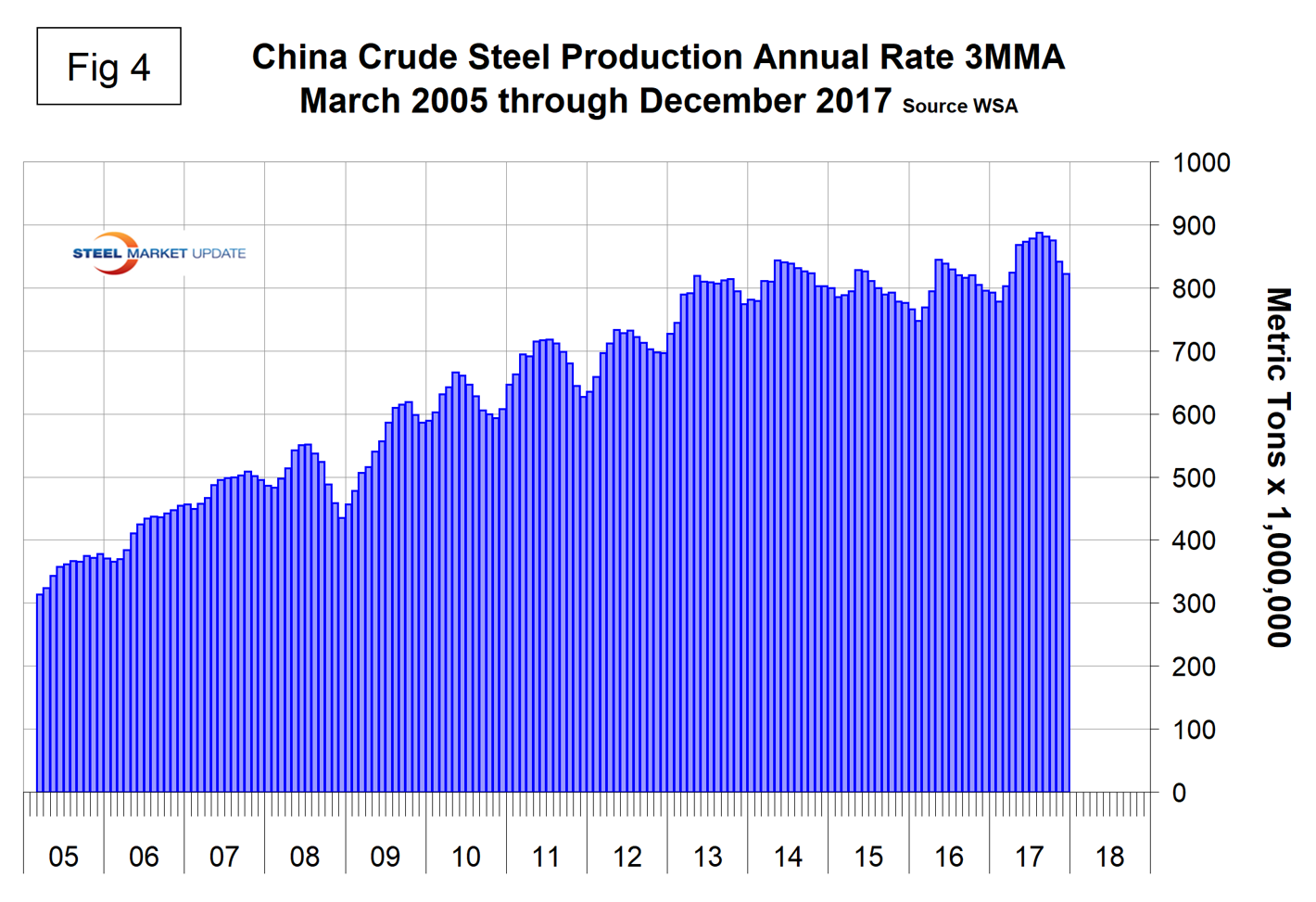

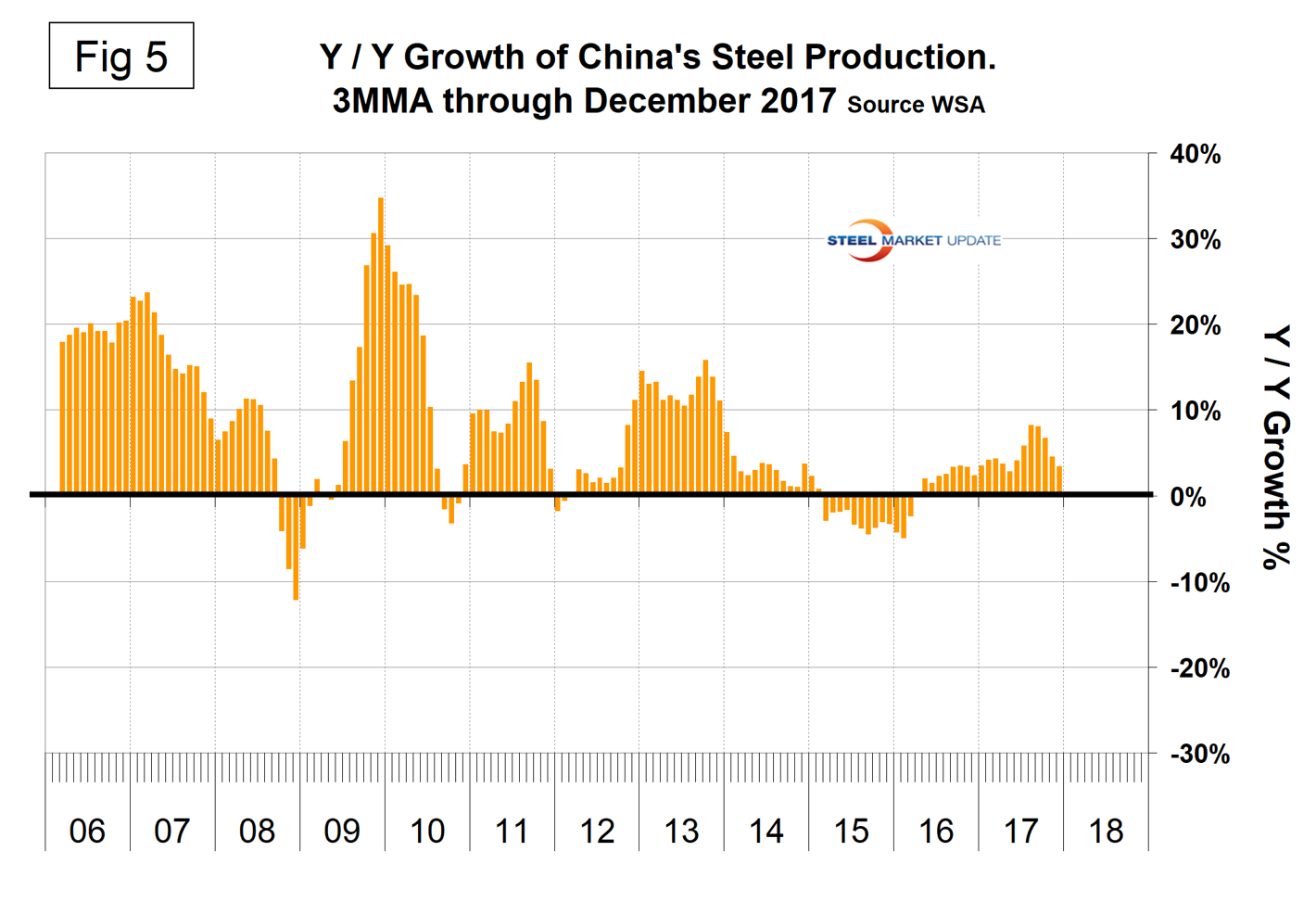

Figure 4 shows China’s production since 2005 and Figure 5 shows the year-over-year year growth. China’s production, after slowing for 13 straight months year over year, returned to positive growth each month in May 2016 through December 2017. Chinese production may slow again as a result of government-mandated cutbacks that began Dec. 15 in Tangshan and surrounding cities to improve air quality.

Table 1 shows that in three months through December year over year, every region except the CIS had positive growth in steel production. At the national level, only Russia contracted. Turkish production was at an all-time high in 2017 at 37.5 million metric tons. EAF output rose by 19 percent to 25.96 million tons and BOF production rose by 2.2 percent to 11.56 million tons.

North American steel production jumped by 8.6 percent in the three months. Within North America, the U.S. was up by 7.2 percent, Canada was up by 26.9 percent and Mexico by 2.9 percent. From October through December, Canada had the highest production since Steel Market update began tracking the data in January 2012. In the 12 months of 2017, 115.3 million metric tons of steel were produced in NAFTA of which 70.8 percent was made in the U.S., 11.9 percent in Canada and 17.3 percent in Mexico. Other Europe led by Turkey had the highest regional growth rate in three months through December year over year. Asia as a whole was up by 3.8 percent.

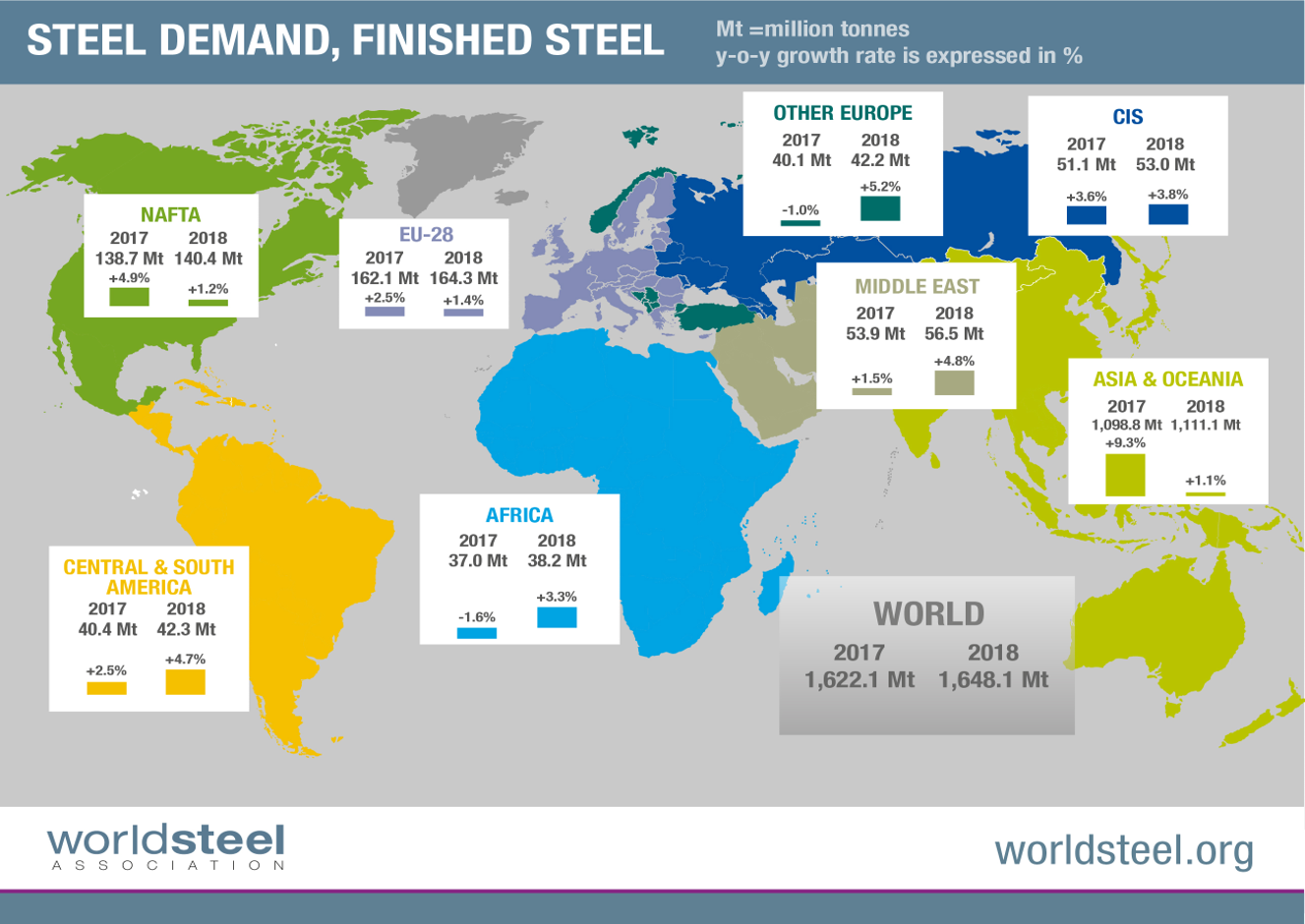

The World Steel Association Short Range Outlook for apparent steel consumption in 2017 and 2018 was revised and published on Oct. 14, 2017 (Figure 6).

Commenting on the outlook, T.V. Narendran, chairman of the World Steel Economics Committee said: “Progress in the global steel market in 2017 has been encouraging. We have seen the cyclical upturn broadening and firming throughout the year, leading to better than expected performances for both developed and developing economies, although the MENA region and Turkey have been an exception. The risks to the global economy that we referred to in our April 2017 outlook, such as rising populism/protectionism, U.S. policy shifts, EU election uncertainties and China deceleration, although remaining, have to some extent abated. This leads us to conclude that we now see the best balance of risks since the 2008 economic crisis. However, escalating geopolitical tension in the Korean peninsula, China’s debt problem, and rising protectionism in many locations continue to remain risk factors. In 2018, we expect global growth to moderate, mainly due to slower growth in China, while in the rest of the world steel demand will continue to maintain its current momentum.”

SMU Comment: WSA increased its April forecast for production in 2018 from 1,548.5 million metric tons to 1,648.1 million metric tons in its October forecast. This would be a projected growth of 1.6 percent in 2018, which based on the present momentum seems low. Globally, steel is back on a roll, driven primarily by construction in the developing world. The emerging and developing economies saw their GDP decline from 2010 through 2015, after which there was a turnaround that the IMF believes will continue through its 2022 forecast.