Market Data

February 14, 2017

Net Job Creation by Industry through January 2017

Written by Peter Wright

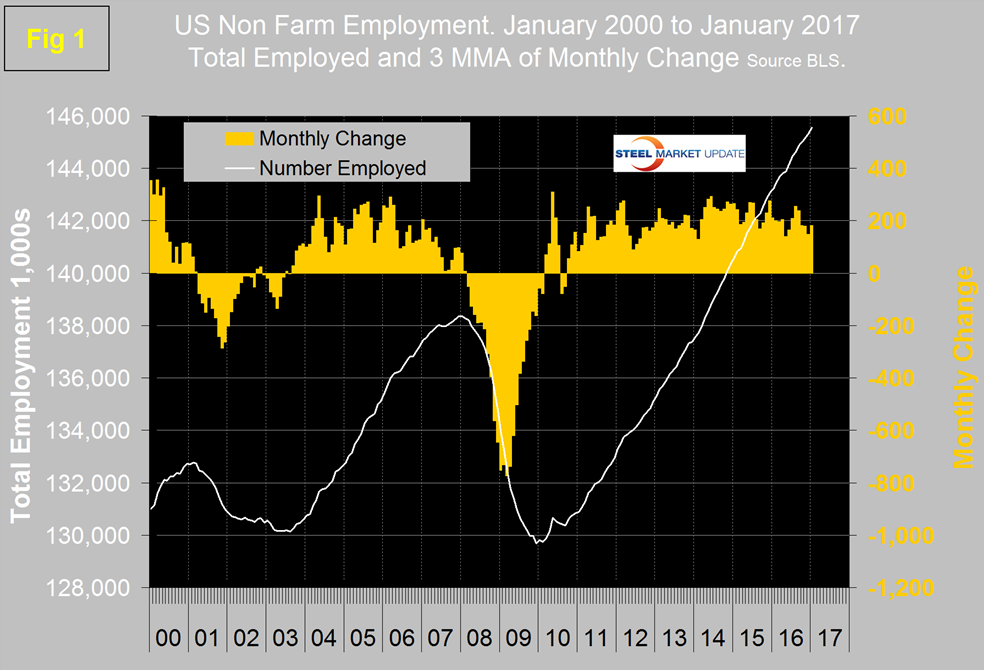

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released the January employment data on Friday and introduced five years of revisions. In January the preliminary result for net job creation was 227,000. November was revised down by 40,000 and December revised up by 1,000. Using a three month moving average (3MMA), the result for January was 183,000 up from 148,000 in December. Figure 1 shows the 3MMA of the number of jobs created as the brown bars since 2000. These numbers are seasonally adjusted by the BLS.

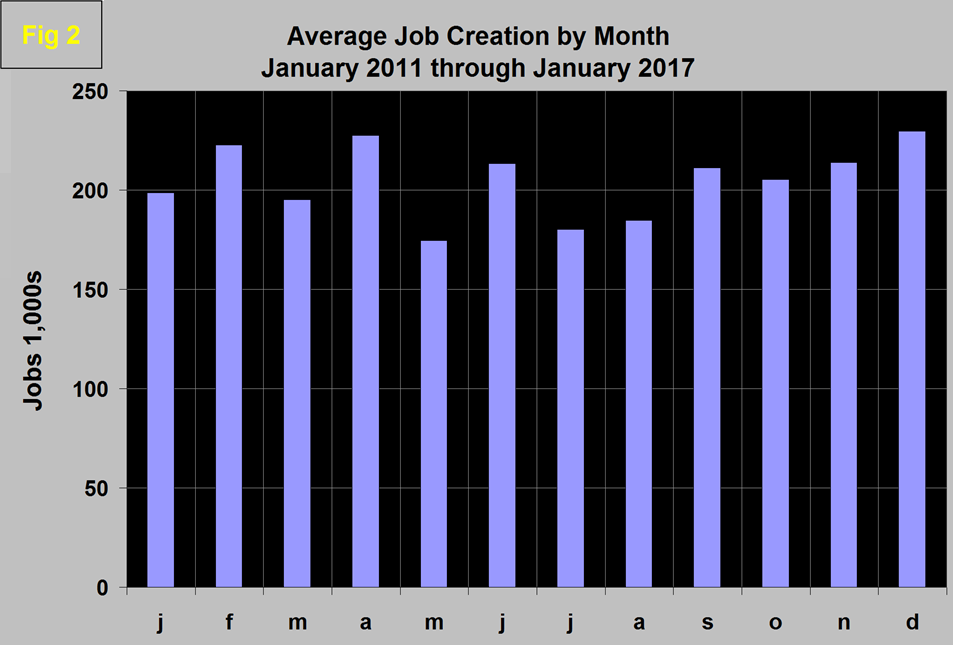

In order to examine if any seasonality is left in the data after adjustment we have developed Figure 2.

In the seven January’s since and including 2011, job creation has been down by an average of 14 percent. This year January was up by 45 percent therefore this is a historically good and unusual result thanks to the mild winter, which boosted employment in construction, and some services.

Total nonfarm payrolls are now 7,189,000 more than they were at the pre-recession high of January 2008. In January, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 3 cents to $26.00, following a 6-cent increase in December. Over the year 2016, average hourly earnings rose by 2.5 percent.

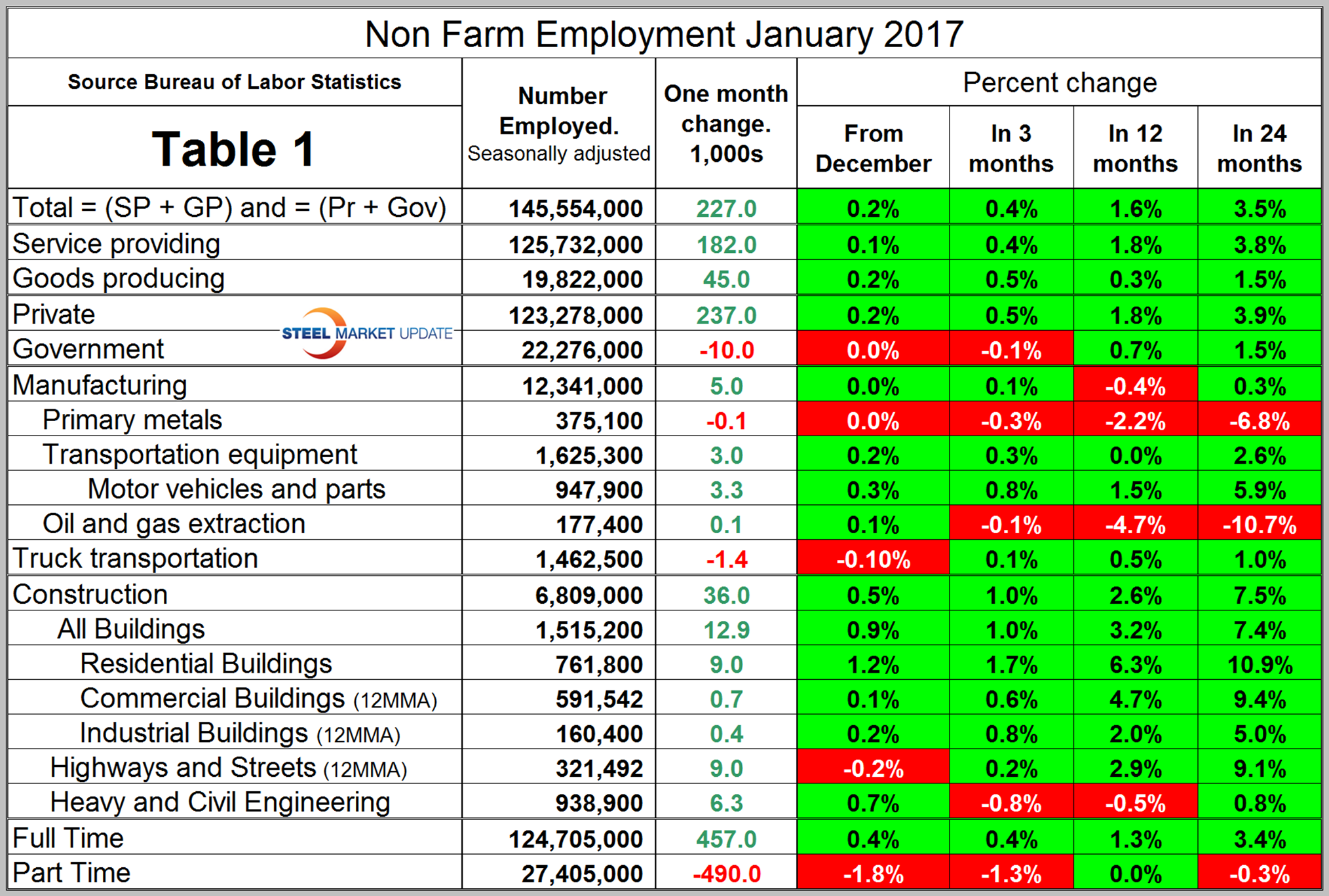

Table 1 slices total employment into service and goods producing industries and then into private and government employees.

Total employment equals the sum of private and government employees, it also equals the sum of goods producing and service employees. Most of the goods producing employees work in manufacturing and construction and the components of these two sectors that we consider to be of most relevance to steel people are broken out in Table 1. In January, 237,000 jobs were created in the private sector and government lost 10,000. The Federal government gained 4,000 as state governments and local governments lost 9,000 and 5,000 respectively. Since February 2010, the employment low point, private employers have added 16,021,000 jobs as government has shed 200,000. In January service industries expanded by 182,000 as goods producing industries driven by construction expanded by 45,000. Since February 2010, service industries have added 13,626,000 and goods producing 2,195,000 positions. This is part of the reason for stagnant wage growth since service industries on average pay less than goods producing such as manufacturing.

In January, manufacturing gained 5,000 positions following an 11,000 gain in December. In the 12 months of 2106 Manufacturing lost 23,000 jobs with an erratic pattern throughout the year ranging from + 28,000 to – 21,000. In January total manufacturing employment was 0.4 percent less than a year ago and 0.3 percent higher than two years ago. Table 1 shows that primary metals have been a weak spot in manufacturing across all four time comparisons. Transportation equipment and motor vehicles have been stronger than total manufacturing on the same basis. Oil and gas extraction gained 100 jobs in the preliminary January result but truck transportation lost 1,400 jobs. This was the first decline in trucking employment after six straight months of gains. Note the subcomponents of both manufacturing and construction shown in Table 1 don’t add up to the total because we have only included those that we think have most relevance to the steel industry. The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls was unchanged at 34.4 hours in January. In manufacturing, the workweek edged up by 0.1 hour to 40.8 hours, while overtime edged down by 0.1 hour to 3.2 hours.

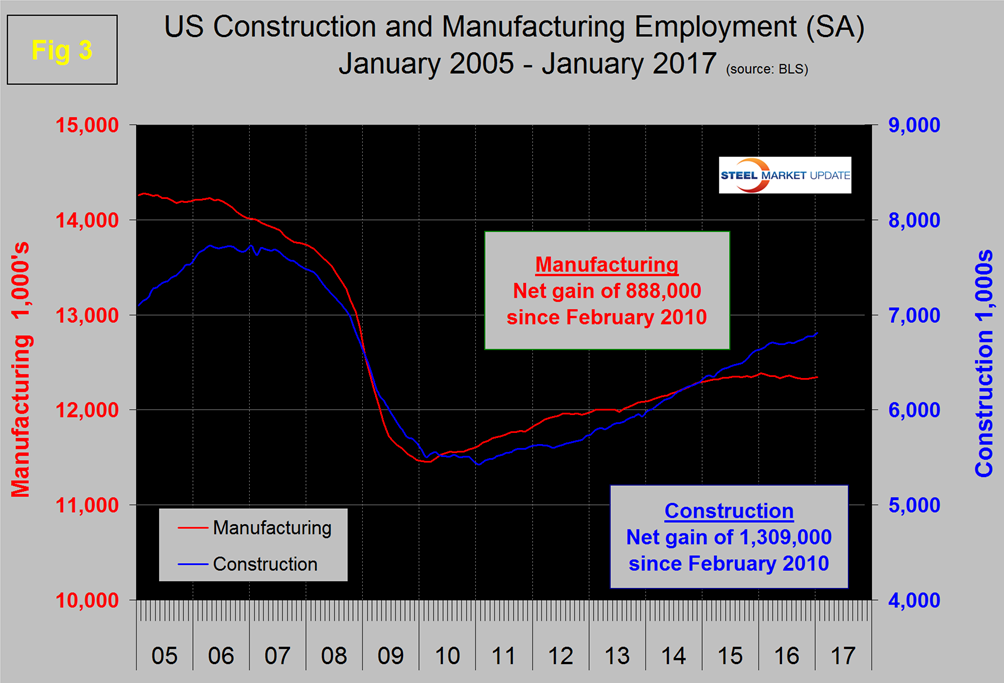

Construction was reported to have gained 36,000 jobs in January and is up by 170,000 since January last year. There is no sign of a slowdown in the growth of construction employment as of the 170,000 just mentioned, 105,000 occurred in the last five months. Some of the major construction sub categories are routinely reported one month in arrears which distorts the data in Table 1. These include, industrial buildings, commercial buildings and highways and streets. Construction has added 1,309,000 jobs and manufacturing 888,000 since the recessionary employment low point in February 2010 (Figure 3).

Construction has leapt ahead of manufacturing as a job creator but the growth of construction productivity is very low (or non-existent), in contrast to manufacturing where it is very high. The difference is the difficulty of automating construction jobs.

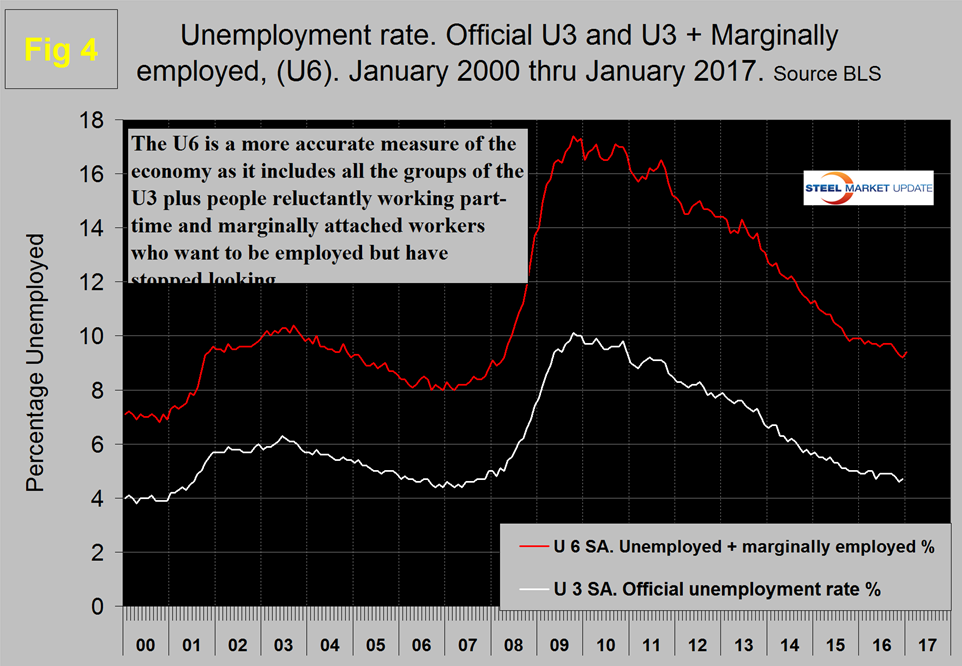

The official unemployment rate, U3, reported in the BLS’s Household survey (see explanation below) came in at 4.8 percent which was up from 4.6 percent in November but the same as October. This number doesn’t take into account those who have stopped looking. The more comprehensive U6 unemployment rate was down from 9.9 percent in January last year to 9.4 percent in this latest report (Figure 4).

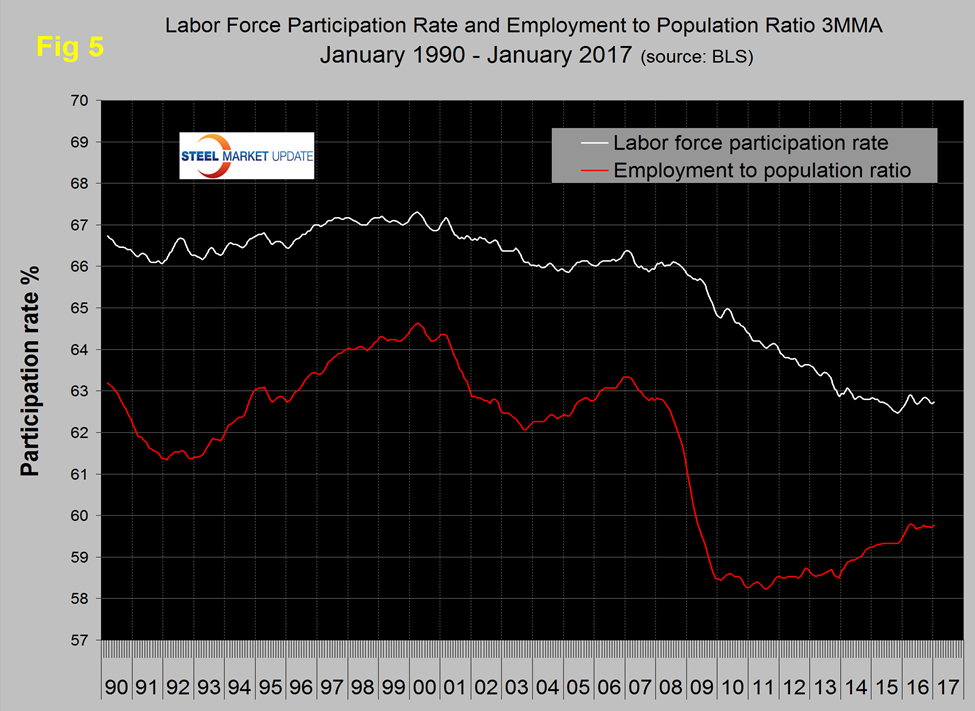

U6 includes workers working part time who desire full time work and people who want to work but are so discouraged that they have stopped looking. The differential between these rates was usually less than 4 percent before the recession but is still 4.6 percent. Neither U3 nor U6 have made much progress in the last year. It has been estimated that the economy needs to create about 150,000 jobs per month to keep up with population growth. In the last 13 months the average job creation has been 190,000 so the impact on unemployment has only been about 40,000/month. The employment participation rate is accurately reported in the press as going nowhere. In January 2017 the rate was 62.7 percent which only slightly better than the 62.6 percent of January last year. We’re not sure that we understand what this is a percentage “of” because of the multiple descriptions of the labor pool. Another measure is the number employed as a percentage of the population which we think is much more definitive. In January this measure was 59.9 percent up from 59.6 percent in January last year. There has been a gradual improvement in employment to population ratio since late 2011. Figure 5 shows both measures on one graph.

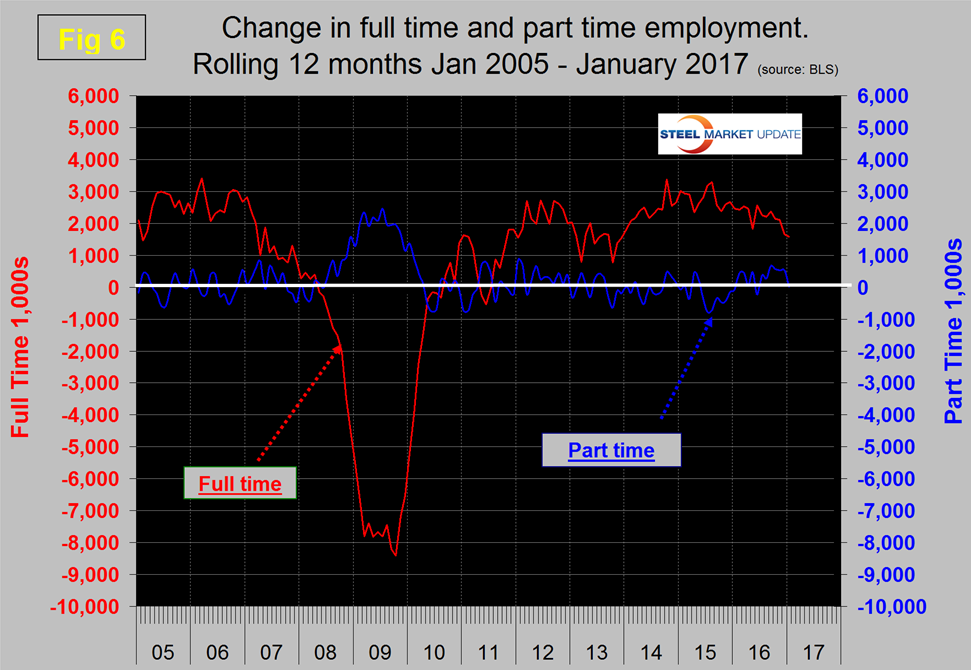

In the 25 months since and including January 2015 there has been an increase of 4,771,000 full time and a loss of 101,000 part time jobs. Figure 6 shows the rolling 12 month total change in both part time and full time employment. F

Frequently in the press we read that a large part of job creation is in part time employment which in some months is true, but the part time numbers are extremely volatile. This data comes from the Household survey and part time is defined as < 35 hours per week. Because the full time/part time data comes from the Household survey and the headline job creation number comes from the Establishment survey, the two cannot be compared in any particular month. To overcome the volatility in the part time numbers we have to look at longer time periods than a month or even a quarter which is why we look at a rolling 12 months for this component of the employment picture in Figure 6.

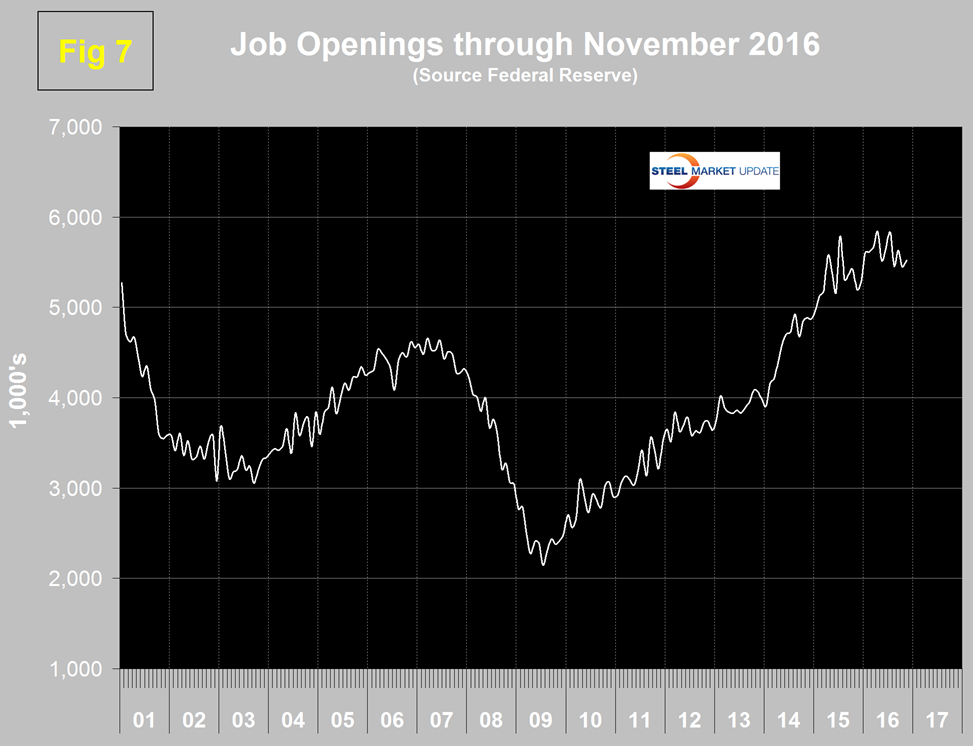

The job openings report known as JOLTS is reported on about the 10th of the month by the Federal Reserve and is over a month in arrears. Figure 7 shows the history of unfilled job openings through November when openings stood at 5,522,000 not far off the all-time high of 5,845 in April. There has been an improving trend since mid-2009.

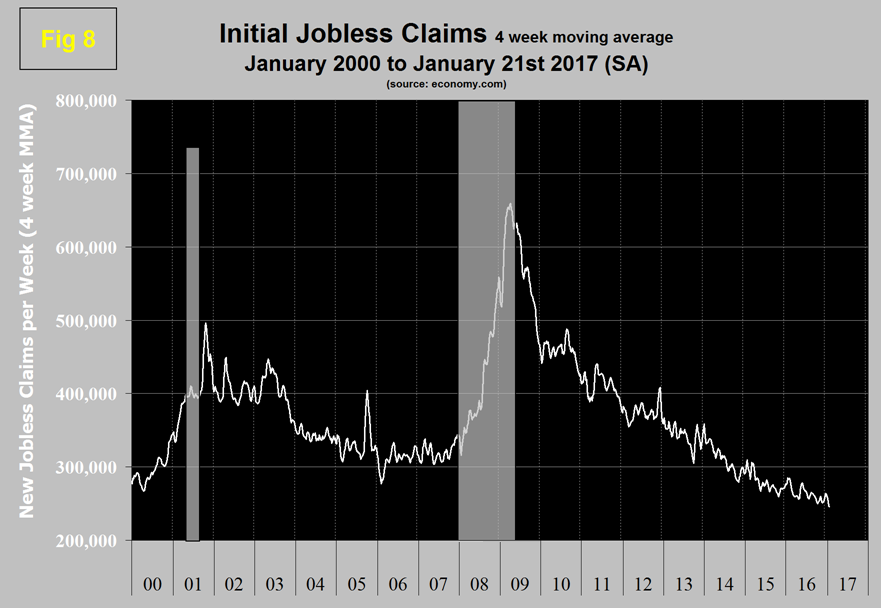

Initial claims for unemployment insurance, reported weekly by the Department of Labor have continued their downward drift this year and in w /e January 21st were 259,000 with a four week moving average of 245,000. This marks the longest streak since 1973 of initial claims below 300,000. (Figure 8). The result for w/e November 12th at 233,000 was the lowest since April 1974.

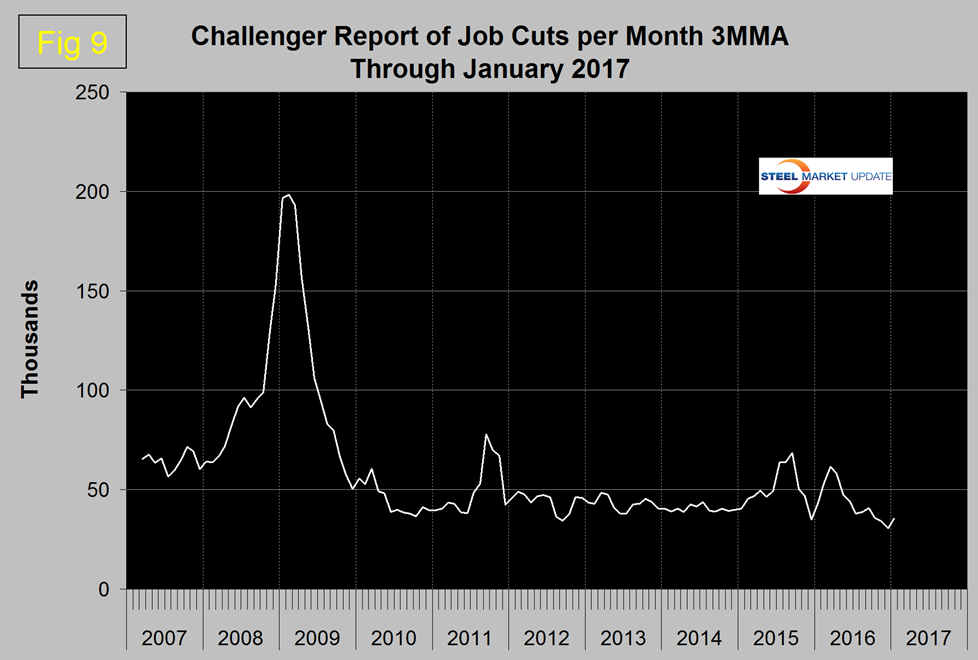

The last piece of the employment puzzle that we examine is the Challenger report which measures job cuts monthly (Figure 9). This data also tends to be quite erratic therefore again we examine a rolling 12 months and can see that job cuts decreased for most of 2016 but ticked up a little in January.

SMU Comment: January was the 75th consecutive month of job growth and the latest data was encouraging. In the last 12 months six have exceeded 200,000 jobs created per month and one of these was January however it does look as though a gradual slowdown is occurring. The high months in 2015 were lower than 2014 and that trend continued into 2016. Manufacturing data has been disappointing this year as construction has been encouraging. Primary metals have had only three positive job creation months since December 2014. The road hauling sector had positive growth every month in H2 2016 so it remains to be seen if the losses in January were just a blip. Job losses in the oil fields have halted. The results for manufacturing and construction are sign posts for steel sales activity. In the big picture, layoffs are historically low and job openings are close to all-time highs therefore there seems to be no reason for pessimism.

Explanation: On the first Friday of each month the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the employment data for the previous month. Data is available at www.bls.gov. The BLS reports on the results of two surveys. The Establishment survey reports the actual number employed by industry. The Household survey reports on the unemployment rate, participation rate, earnings, average workweek, the breakout into full time and part time workers and lots more details describing the age breakdown of the unemployed, reasons for and duration of unemployment. At SMU we track the job creation numbers by many different categories. The BLS data base is a reality check for other economic data streams such as manufacturing and construction and we include the net job creation figures for those two sectors in our “Key Indicators” report. It is easy to drill down into the BLS data base to obtain employment data for many sub sectors of the economy. For example, among hundreds of sub-indexes are truck transportation, auto production and primary metals production. The important point about each of these hundreds of data streams is in which direction they are headed. Whenever possible we at SMU try to track three separate data sources for a given steel related sector of the economy. We believe this gives a reasonable picture of market direction. The BLS data is one of the most important sources of fine grained economic data that we use in our analyses. The States also collect their own employment numbers independently of the BLS. The compiled state data compares well with the federal data. Every three months SMU examines the state data and provides a regional report which indicates strength of weakness on a geographic basis. Reports by individual state can be produced on request.