Market Data

October 12, 2015

Global Economic Outlook: IMF October 2015

Written by Peter Wright

We include here an abridged statement from the IMF that was released last week and in which the commodity situation looms large. Followed by our Steel Market Update data analysis and comments about the future of global and domestic steel demand through 2020.

![]() Transcript of the World Economic Outlook Press Conference

Transcript of the World Economic Outlook Press Conference

Good morning. I have the great pleasure to be here in Lima to present the October 2015 WEO forecasts and analysis. This forecast comes as the world economy is at the intersection of three very powerful economic forces. These forces have a particular impact in emerging markets and low-income economies. Peru will certainly be feeling these forces.

First of all, there is China’s transformation. The economy is rebalancing from exports and public investment to consumption, from manufacturing to services. This is both healthy and necessary in the longer term, but in the near term there are implications for China’s growth and for its trading relationships with foreign countries.

The second major current in the world economy is the fall in commodity prices, which, of course, is not unrelated to China’s growth experience. After years of high demand resulting in high prices for commodities and high investment in commodity-producing sectors, China’s slowing starting earlier in this decade has led to a trend decline, a trend decline that has accelerated in recent weeks.

The third major current, of course, is the impending normalization of US monetary policy. This is also a healthy and a necessary development; it is healthy in light of the relatively favorable growth in the US. But there will be global repercussions, indeed have already been global repercussions, especially for the emerging and low-income countries.

So, amid these very important developments, near-term growth remains moderate and uneven. We see higher downside risks than we saw at the time of our last July update of our forecasts. The Holy Grail of robust and synchronized global expansion remains elusive.

Let me turn to our projections which I want to emphasize are what we view as the most likely outcomes, but there are also downside risks and risks seem more tilted to the downside than they did just a few months ago.

For the world, growth was 3.4 percent last year. We are projecting 3.1 percent for 2015, 3.6 percent for 2016. Both the 2015 and 2016 projections are down by 0.2 percentage points compared to what we thought in July.

These aggregate numbers for the world reflect disparate fortunes between advanced economies and the emerging and low-income group. For the advanced economies, overall growth was 1.8 percent in 2014. Our projections for 2015 and 2016 are 2.0 and 2.2 percent, respectively, and also downgraded from what we believed would be the case in July. We see a pickup this year in the US and in the euro area. Japan had a very strong Q1 showing, but it is beginning to look a little wobbly.

Within the advanced economies, of course, there is also heterogeneity. Some of the advanced economies are commodity exporters. So, Canada, but also Norway, Australia are facing headwinds both from terms of trade effects and also from important effects on their investment sectors, something we have also seen in the US energy sector.

What about emerging and low-income economies? Commodity price falls are having their most intense effects there, and these countries, of course, are more than half of world GDP and the lion’s share of world GDP growth.

2015 is projected to be the fifth straight year in which emerging and low-income growth declines. Growth was 4.6 percent in 2014. We are projecting 4.0 percent this year and for next year 4.5 percent. Both of these numbers are down 0.2 percentage points compared to our July forecast.

Now, commodities are an important, perhaps the most important part of the story, but they are not everything. Again, different countries face different risks. In some, political instability is a dominant factor; there are overhangs of debt and overinvestment in commodity sectors and, in some countries, a loss of fiscal credibility. Of course, the countries with multiple challenges are facing the lowest growth and the most turbulent.

Why do we think there will be a growth rebound in emerging markets next year? Well, a number of large emerging markets are having an especially difficult time this year. If we look at Brazil, we are projecting -3 percent for this year, -1 percent for next year. That is negative growth next year but is still a substantial improvement, and these bring up the aggregate numbers. Also, investment effects due to commodity price declines are likely to abate as commodity prices stabilize.

Now, as I said, we view these numbers as the most likely outcomes, but there are certainly risks to the outlook and these risks seem to have rotated toward the emerging markets and the low-income economies.

Emerging markets have built resilience, of course, over recent years with greater exchange rate flexibility, higher levels of international reserves, more FDI and domestic currency external borrowing, and generally stronger policy frameworks. But that being said, in the face of the downside risks that exist, there is more limited policy space than was available some years ago.

In the emerging world, countries have to get ready for the Fed to move on interest rates. They can do so by improved surveillance of the financial sector; more discouragement of foreign exchange-denominated borrowing; greater encouragement of equity inflows, which is not unrelated to the governance environment, and finally, smart fiscal frameworks that maintain sustainable fiscal accounts and credibility while preserving growth and at the same time protecting the most vulnerable in society.

In advanced economies, deflation very much remains a threat, and we also see it in some parts of Asia. Therefore, monetary accommodation, where appropriate, remains advisable, as does fiscal expansion where there is fiscal space. Crisis legacies such as nonperforming loans in a number of countries, the need to strengthen the banking union in the euro area, these remain imperative to build a more resilient system.

There are some measures from which all economies in the world can profit and some of these support global aggregate demand, which remains insufficient. It should be attractive at historically low global interest rates. Targeted structural reforms in labor markets, product markets, reforms that improve the business climate, can be profitably carried out in many countries.

There are many cooperative efforts that need to be pursued in order to raise the resilience of the international financial system: regulatory cooperation; work on the global safety net, including IMF quota reform, an important piece of unfinished business from five years ago.

The WEO underlines that all countries face challenges in the current environment and it raises the question of how to finally find the Holy Grail of robust and synchronized growth. The right policy upgrades are challenging to implement, but they will benefit not only each country individually but the resilience of the international system. With that, we invite your questions.

SMU Data Analysis

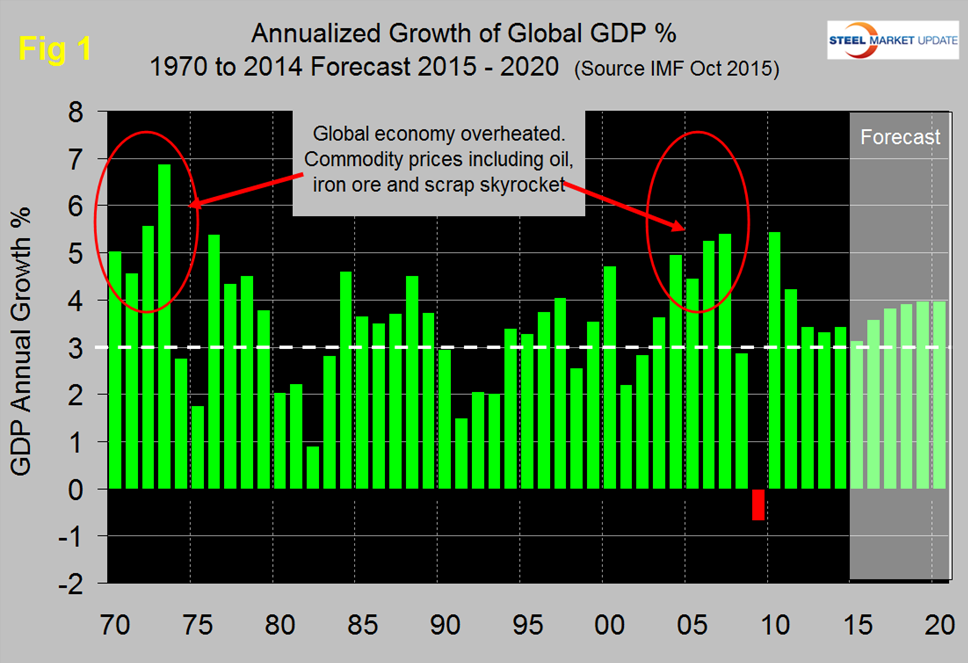

Figure 1 shows the growth of global GDP since 1970 with this month’s IMF forecast through 2020.

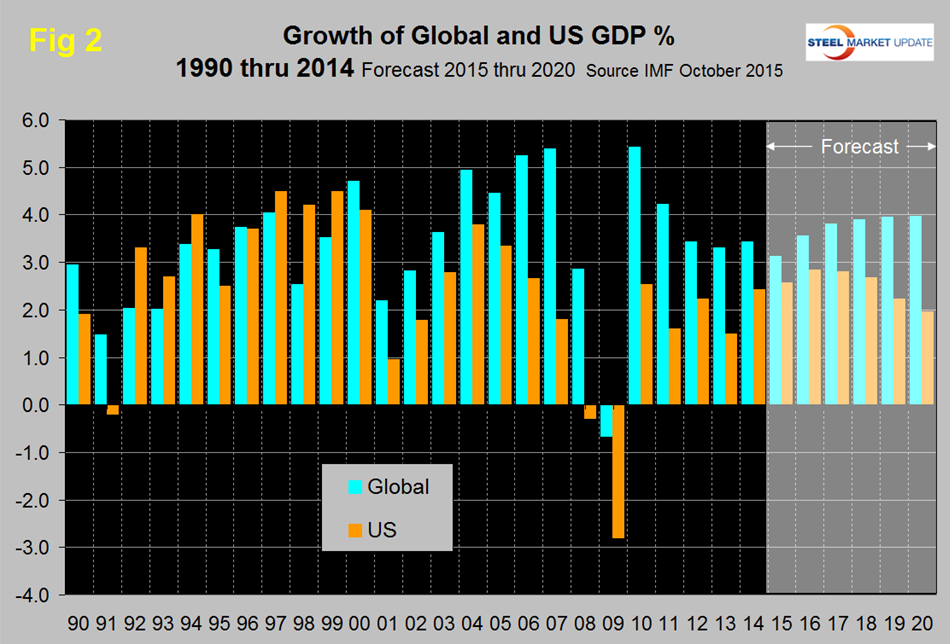

We have highlighted the periods of the early seventies and the mid 2000s when the commodity bubbles prevalent at those times were driven by unusually high and sustained global growth. The collapse of the commodity bubble in the last decade coincided with the US banking and housing crisis setting up the perfect storm. Global growth has been unusually flat in the years 2012 through 2015 followed by a forecasted slow growth through 2019 and flat in 2020. Prior to the 2001 recession, the US held its own in the economic growth stakes but between 2001 and 2008, growth in the US averaged 1.84 percent less per year than the growth of the global economy as a whole (Figure 2).

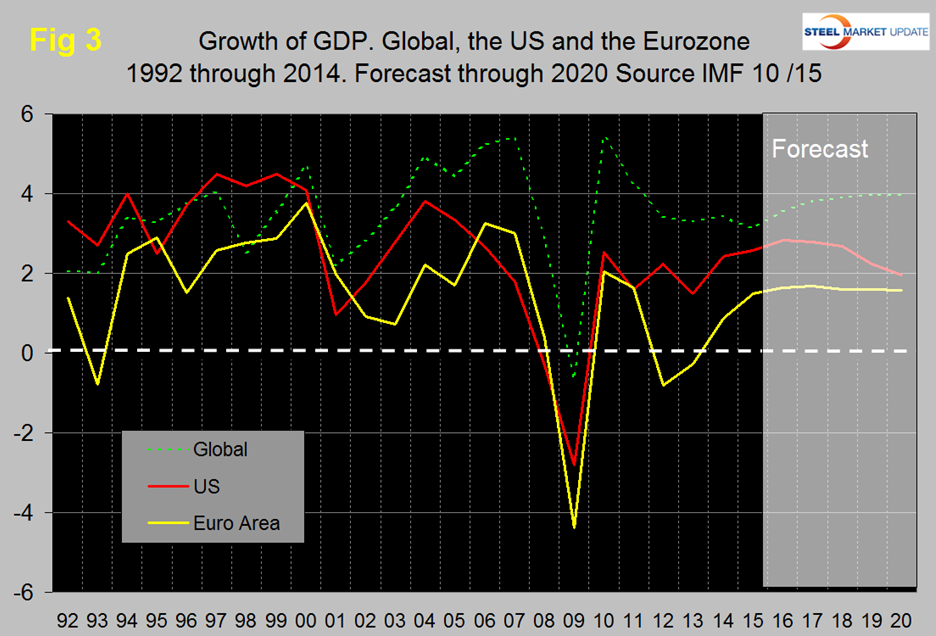

In the years 2011 through 2013 that gap narrowed to 1.36 percent and in 2015 is forecast to be only 0.5 percent. Global growth is now projected to gradually climb back to 3.97 percent in 2020, the discrepancy with US widening again. The US has outperformed the Eurozone in every year since 2008 and is forecast to continue to do so through 2020 (Figure 3).

The gap will narrow as we approach the end of this decade. Figure 4 shows the growth comparison between emerging and developing economies and the advanced economies, that gap is projected to widen in the second half of this decade.

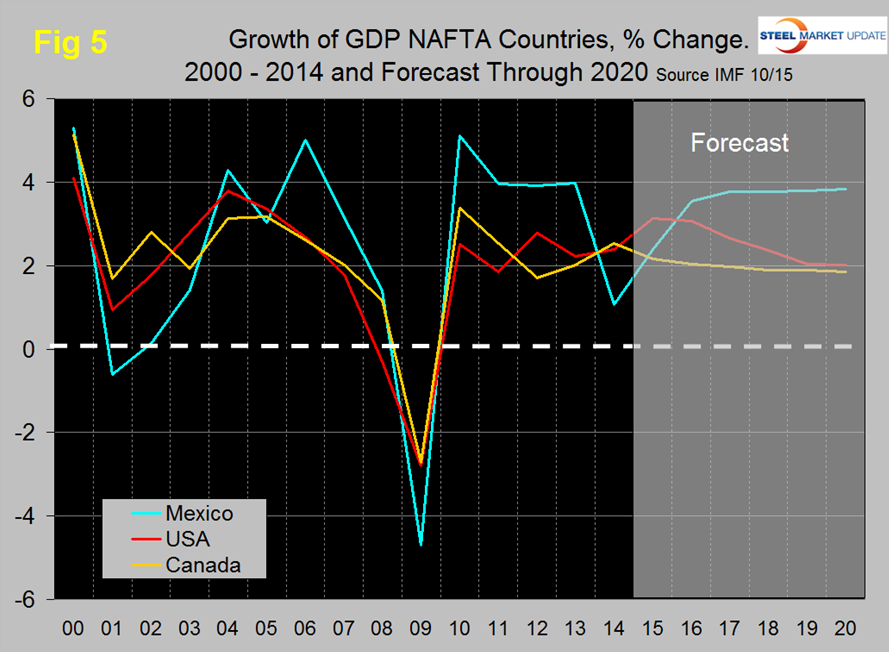

Within NAFTA, Mexico had the lowest rate of growth in 2014 but is forecast to re-take the lead next year and to widen the gap with the US through the end of the decade (Figure 5).

Canada is forecast to be relatively flat in that time period.

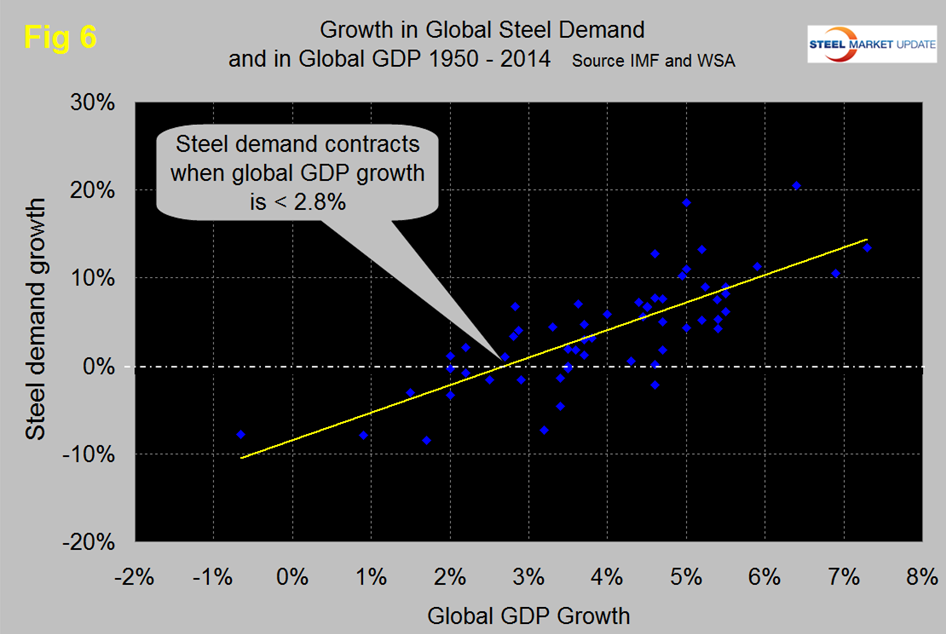

There is a relationship between the growth of GDP and steel demand at both the international and national level which also extends to other commodities such as cement. There are two interesting aspects to this relationship. First the cyclical change in steel demand is vastly more volatile than the change in GDP which we attribute to the inventory response throughout the supply chain. Secondly as discovered by our friends at “Steel Guru” 1 percent growth in GDP does not result in 1 percent growth in steel demand. At the global level it takes a 2.8 percent increase in GDP to get any increase in steel demand (Figure 6).

This is a long term average over a period of 65 years and based on the added volatility of steel can be a predictor of the immediate future. For example after the disastrous decline in steel demand in 2009 there was no doubt that a huge cyclical rebound would occur as inventory managers throughout the world began to react to the economic recovery. If the IMF forecast proves to be correct then the growth in steel demand will improve to around 3 percent by 2017. This is much better than current World Steel Association data through August which suggests that global steel demand will decline in 2015. In the US steel market it requires about 2 percent growth in GDP to generate growth in steel demand therefore again if current forecasts prove to be correct regarding the US economy we can expect steel demand to expand through 2017 then tail off as we approach 2020.