Market Data

June 10, 2014

European Union Pulls Out the Big Guns to Fight Deflation

Written by Peter Wright

We are including this article because it puts the Fed’s post-recession activities into perspective. Our recollection is that the European central bankers scoffed at the Federal Reserve quantitative easing and TARP programs when they were initiated in 2008.

The European Central bank, (ECB) has taken the single currency block into uncharted waters by sending the interest rates on bank deposits into negative territory as part of a package of extraordinary measures to ward off deflation.

From Wednesday this week banks will be charged 0.1 percent to park money with the ECB in an attempt to force them to lend to the “real economy.” This is the first time any central bank has introduced such a punitive measure.

Mario Draghi, the president of the ECB, unveiled the plan as he lowered the main interest rate from 0.25 percent to 0.15 percent, launched a 400 billion Euro cheap loan scheme for businesses and signaled that full quantitative easing was the only weapon left in the public arsenal.

The ECB also downgraded its 2014 growth forecast to 1 percent from 1.2 percent and sharply lowered its inflation outlook. Prices are expected to rise by only by 0.7 percent this year, 1.1 percent in 2015 and 1.4 percent in 2016. A long way from its 2 percent target. Although Mr. Draghi said he saw no sign of deflation yet, he added, “We are reacting to the risk of a too prolonged period of low inflation. The longer it lasts the higher the risk. Policy makers fear nothing more than a deflation trap because there is little they can do to haul an economy out of a negative price spiral. Eurozone inflation in April was 0.5 percent, a nasty surprise for markets last week.

In an unprecedented intervention that economists termed, “the big bazooka”, the ECB also unleashed billions of Euros of liquidity to ensure that the regions banks are flush with cheap money. The ECB will no longer sterilize its 165 billion Euro of existing bond purchases, effectively injecting a small dose of quantitative easing, (QE) into the system, continue to conduct exceptional money market operations and accept less secure assets as collateral for liquidity from the banks. The ECB signaled plans to print money to buy corporate debt in the asset backed securities market.

Markets broadly welcomed the move with European shares rising and government borrowing costs falling. The Euro briefly fell to a four month low before recovering to close slightly higher at 1.36 against the US Dollar. Despite the scale of the intervention, Mr. Draghi said, “I consider we have reached the lower bound today,” indicating there is nothing more the ECB can do with interest rates. Hinting at the prospects of QE he then said, “We are not finished here,” and that the decisions made by the governing council were unanimous.

Questions have been raised about the effectiveness of negative interest rates. Jamie Caruana, head of the Bank of International Settlements, said this week, “I am not convinced that banks will lend more if there is a negative interest rate on deposits. They may simply decide to shrink their balance sheets.”

In a dual pronged attempt to boost lending to the real economy, Mr. Draghi said the ECB combined negative rates with a new 400 billion Euro cheap loan scheme, christened the targeted longer term re-financing operation. Modeled on the Bank of England’s Funding for Lending scheme it will enable Eurozone banks to access cheap funds if they support lending to households and non-financial corporations.

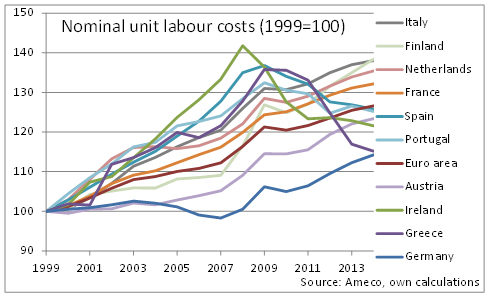

SMU Comment: As bad as the implications from this article are it does not address one of the biggest problems inherent in the Euro area which is the discrepancy of unit labor costs between Germany and the southern nations. Weaker high labor cost nations cannot de-value their currencies to correct trade imbalances. In our opinion the Euro area is unsustainable in its present form which has huge implications for steel trade if countries like Spain and Italy revert to a national currency or to a second tier Euro. Greece, Ireland and Portugal have made good progress in reducing unit labor costs based on austerity programs but Italy and France have made no progress at all and Germany still has best performance in the EU, (Figure 1).

From the UK newspaper The Independent: A common currency and budget simply aren’t conducive to large clubs. Yes, homogenous countries can benefit from sharing a currency — it can reduce costs for exporters, for example. However, the euro locked vastly different countries, cultures and economic structures into one monetary system, under a single interest rate, forever binding together the problems of all its members, debtor or creditor, large or small. The result: a sluggish economic block and a huge amount of political resentment on all sides. We would not repeat this mistake if we were to start from scratch.

From the NY Times on last week’s elections for the European parliament: An angry eruption of populist insurgency in the elections for the European Parliament rippled across the Continent on Monday, unnerving the political establishment and calling into question the very institutions and assumptions at the heart of Europe’s post-World War II order. Four days of balloting across 28 countries elected scores of rebellious outsiders, including a clutch of xenophobes, racists and even neo-Nazis. In Britain, Denmark, France and Greece, insurgent forces from the far right and, in Greece’s case, also from the radical left stunned the established political parties.

The insurgents’ success has upended a once-immutable belief, laid out in the 1957 Treaty of Rome, that Europe is moving, fitfully but inevitably, toward “ever closer union. (Source: The Times of London)